Water risk is one of the most significant ecological threats facing our planet. Two billion people globally, a quarter of the population, do not have safe drinking water, while 3.6 billion lack access to safe sanitation. Water stress impedes economic development and food production, which further compromises the health and wellbeing of the population. It can also lead to social tension, conflict and displacement.

The 2024 Ecological Threat Report (ETR) is the fifth edition of a quantitative analysis of ecological threats in 207 independent states and territories. Among the four ecological threats examined in the ETR is water risk, which assesses the proportion of a population that does not have access to clean drinking water.

In addition to the threats posed to human communities by a lack of access to water, this edition of the report also explores some its drivers. Specifically, we compare water risk to the Positive Peace Index (PPI), which can be used as a proxy for the strength of governance, infrastructure and social cohesion in a country. This comparison allowed for an analysis water risk levels within the context of how governments manage their available water resources.

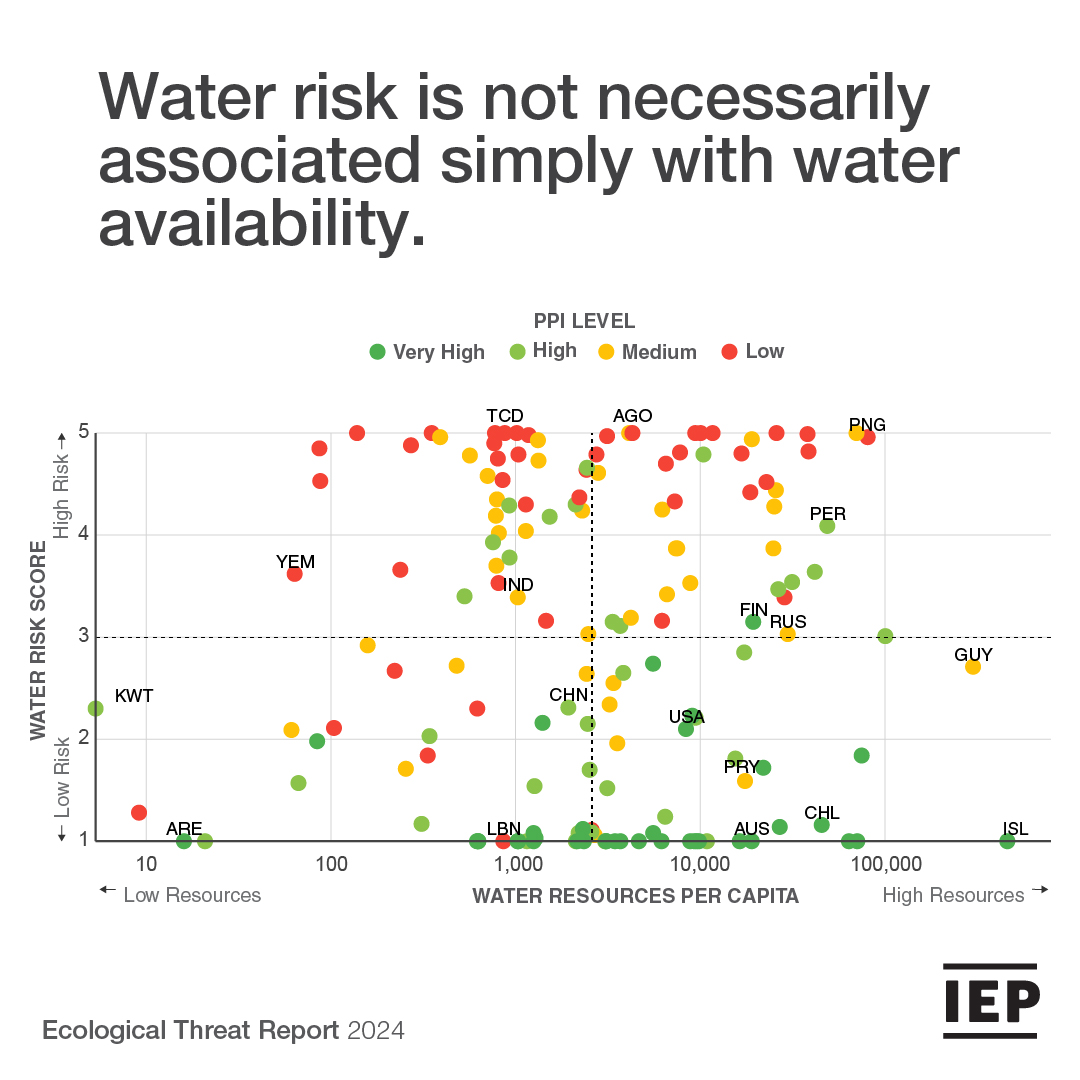

The report found little to no correlation between the amount of renewable water available in a country’s territory and its level of water risk, but there was a correlation between levels of water risk and countries’ performance on the PPI. Some of the countries with the highest levels of water risk, such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Gabon, have among the highest amount of internal water resources per capita in the world but score low on the PPI. Conversely, the countries with low levels of water risk, despite having limited water resources, tend to have high levels of Positive Peace.

This finding underscores the importance of effective governance and societal stability in managing water-related challenges. It suggests that the quantity of internal water resources within a country’s borders is not the primary determinant of water security – rather strong governance systems and effective infrastructure are critical.

For example, Iceland and the United Arab Emirates (ARE) both have a score of 1 on the water risk scale, indicating the lowest level of risk, despite vast differences in their water resources. Iceland has 459,000 cubic metres of renewable water per person, while ARE has only 16 cubic metres per person. The ARE’s ability to manage its limited water resources is due to its substantial financial resources, which help drive its very high PPI score, reflecting robust governance and infrastructure, such as extensive desalination plants, which provide 42 per cent of the country’s drinking water.

The ARE’s water infrastructure and strong government prevent the country from facing similar levels of water risk than those faced by other arid countries, such as nearby Yemen. Despite having almost four times more water resources per capita, Yemen faces significantly higher water risk than ARE. This is largely due to Yemen’s weak governance and infrastructure, as reflected its low PPI score. Only 30 per cent of the Yemeni population have access to a reliable water network, and 17.8 million people lack safe water access, leading to severe public health issues, including cholera outbreaks. The ongoing conflict in Yemen exacerbates these challenges, highlighting the importance of strong governance and infrastructure in managing water resources and mitigating risks, especially in countries with limited resources.

PNG also illustrates that abundant natural water resources do not guarantee low water risk. Despite having over 80,000 cubic metres of internal water resources per capita, PNG faces high water risk due to inadequate infrastructure and weak governance, as reflected in its low PPI score. Many people in PNG, particularly in rural areas, lack access to clean water and sanitation facilities. The country’s water infrastructure suffers from poor maintenance and limited coverage, compounded by socio-economic barriers and ecological threats such as flooding. These governance challenges hinder effective water management, particularly in times of increased ecological threat, highlighting that strong institutions are crucial in mitigating water risks.

Some countries are outliers on this chart, due in part to their unique water systems. For example, Egypt has low water risk despite having minimal water resources and a low PPI score. This discrepancy can be largely attributed to Egypt’s strategic management of the Nile River, which supplies about 98 per cent of its renewable water resources. The construction of the Aswan High Dam is a pivotal infrastructure project that helps regulate the flow of the Nile, providing essential water for irrigation and power generation. Additionally, Egypt has substantially invested in desalination and wastewater treatment to supplement its water supply and quality. These efforts illustrate how targeted investments, and technological innovations can significantly mitigate water risks, even in countries with limited natural resources or governance challenges.

In contrast to Egypt, Peru demonstrates relatively high levels of Positive Peace and abundant water resources but experiences higher-than-average water risk. Moreover, like Egypt, Peru has a unique source of water resources, relying heavily on glacial runoff for irrigation, particularly in the arid coastal regions. The country is home to approximately 70 per cent of the world’s tropical glaciers, which are crucial for supplying water during the dry season. However, these crucial water resources have shrunk by over 40 per cent since the 1970s, rendering an age-old form of irrigation unreliable and increasingly insufficient for meeting the nation’s water demands.

The original rapid melting led to contamination of water resources due to runoffs from croplands, mining sites, and natural rock minerals that previously were not in contact with glacier runoff. However, in recent years, as the glaciers further retreat, there is an increased likelihood of decreased glacial runoff that many regions in Peru rely on as a form of natural irrigation. The Cordillera Basin, which houses many of Peru’s glaciers, is already experiencing decreased dry-season water flow. These unique geographical challenges further highlight the complexity of water risk and how even countries with relatively strong institutions and abundant resources like Peru are vulnerable to rapid environmental changes and new ecological threats.

However, despite these new ecological threats, Peru’s water risk has been improving. One example of these efforts is Peru’s National Water Authority (ANA)’s collaboration with United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP). These organisations have been working together in Peru for almost a decade to improve irrigation systems and integrated water management. In addition, Peru’s National Superintendence of Sanitation Services enacted a new wastewater treatment plan to combat water risk in March of 2024. Peru’s response to emerging ecological threats and unprecedented pressures on its water supply underscores the critical need for effective governance and robust national services to address the challenges posed by increased climatic variability.

While understanding water risk involves considering various ecological and societal factors, the data shows that the strength of governance and institutions is the key factor for determining a country’s water risk levels. Encouragingly, countries around the world show that strong institutions and infrastructure can overcome a lack of natural resources to provide safe drinking water to their citizens. As the world becomes increasingly water stressed and more prone to extreme weather events like droughts and floods, the effectiveness of governments in maintaining water infrastructure and protecting their country’s natural resources will become more and more critical.