The global economic landscape is undergoing a seismic shift as the United States implements a dual policy approach that poses a serious threat to vulnerable developing economies.

With proposed tariff increases reaching as high as 50% on imports from two dozen countries, alongside significant reductions in official development assistance (ODA), the US has created a perfect storm for nations already walking an economic tightrope.

For countries like Cambodia, where exports to the US represent 36% of GDP, or Lesotho, facing steep 50% tariffs while simultaneously relying on international aid for nearly 7% of its economy, the threat these dual policy shifts represent are more than economic headwinds. This policy convergence disproportionately impacts precisely those nations least equipped to absorb such shocks, creating potential flashpoints for instability across multiple regions already challenged by fragility and conflict.

These tariffs, which usually target economies heavily reliant on exports to the US, arrive at a particularly precarious time for a group of vulnerable countries whose stability and development hinge on trade and international aid.

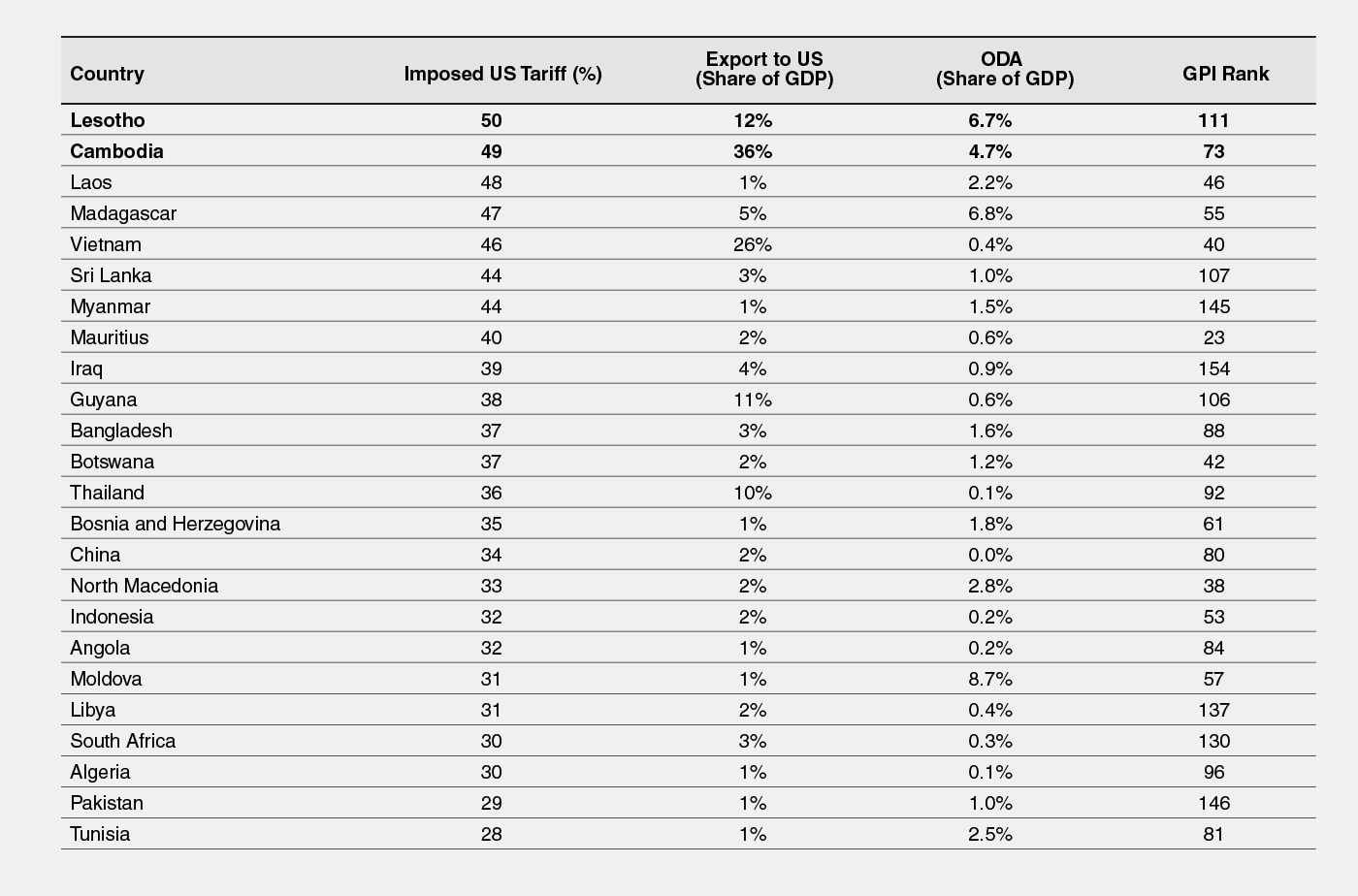

The table below lists the 24 countries facing the highest US import tariffs. The countries most at risk include Lesotho, Cambodia, Vietnam, Guyana, and Thailand — all of which face steep proposed US tariffs ranging from 36% to 50%. For these nations, exports to the US account for a significant share of their GDP. Lesotho and Cambodia, for instance, derive 12% and 36% of their GDP from exports to the US, respectively, making them highly exposed to disruptions in their trade with the US. At the same time, countries like Lesotho Cambodia and Laos and Madagascar also rely heavily on international development assistance, with the ODA in their GDP ranging from 2.2% to 6.8%. The double burden of restricted trade access to the US and shrinking aid flows threatens to destabilise not only their economies but also their social and political landscapes.

The impact of these changes will not be confined to economic hardship. Several of the countries affected already exhibit worrying levels of violence and instability, as captured by their Global Peace Index (GPI) ranking. Iraq, for example, has one of the worst peace scores at 3.006 (ranked 154th globally), while Myanmar, Pakistan, South Africa and Libya also fall into the high-risk category with poor GPI performance. When trade revenues decline and external aid diminishes, governments in fragile states may struggle to maintain essential services, fund security forces, or invest in job creation — particularly for young populations vulnerable to radicalisation and recruitment into armed groups.

What emerges is a troubling feedback loop. Economic contraction caused by tariff barriers reduces state capacity, while the simultaneous withdrawal of development assistance erodes the social safety nets that help prevent unrest. In conflict-affected countries, these pressures can exacerbate existing tensions, increase grievances, and in some cases trigger the resurgence or escalation of violence. Even in relatively less violent yet fragile countries like Sri Lanka— which is also on the receiving end of both tariffs and low aid — the result may be a slow erosion of stability and social cohesion. Compounding this is the increasing trend for ODA to be administered as loans contributing to national debt burdens. This trend is only expected to increase more amidst planned and upcoming ODA cuts.

While the new US tariff regime and aid reductions may be driven by domestic political or strategic concerns, their ripple effects will be deeply felt across a diverse set of export-dependent and aid-receiving nations. For countries that are both economically vulnerable and politically fragile, these policy changes are more than just numbers — they represent an intensification of existing pressures that could push already unstable situations toward crisis. Without careful international coordination and mitigation strategies, the result could be not only economic downturns, but a backslide in peace and development across multiple regions.