More than 34,000 people were killed in Mexico in 2021, marking one of the deadliest years on record. The 2022 Mexico Peace Index (MPI) reveals distinct gendered dynamics of homicide in Mexico. Men accounted for the vast majority of homicide victims in Mexico last year, at nearly 89 per cent of the total.[1] While both male and female homicides tend to be linked to organised crime trends, female deaths also show a strong association with intimate partner violence. According to official statistics, nearly one in five female homicides occur in the home, compared to one in thirteen for male homicides.

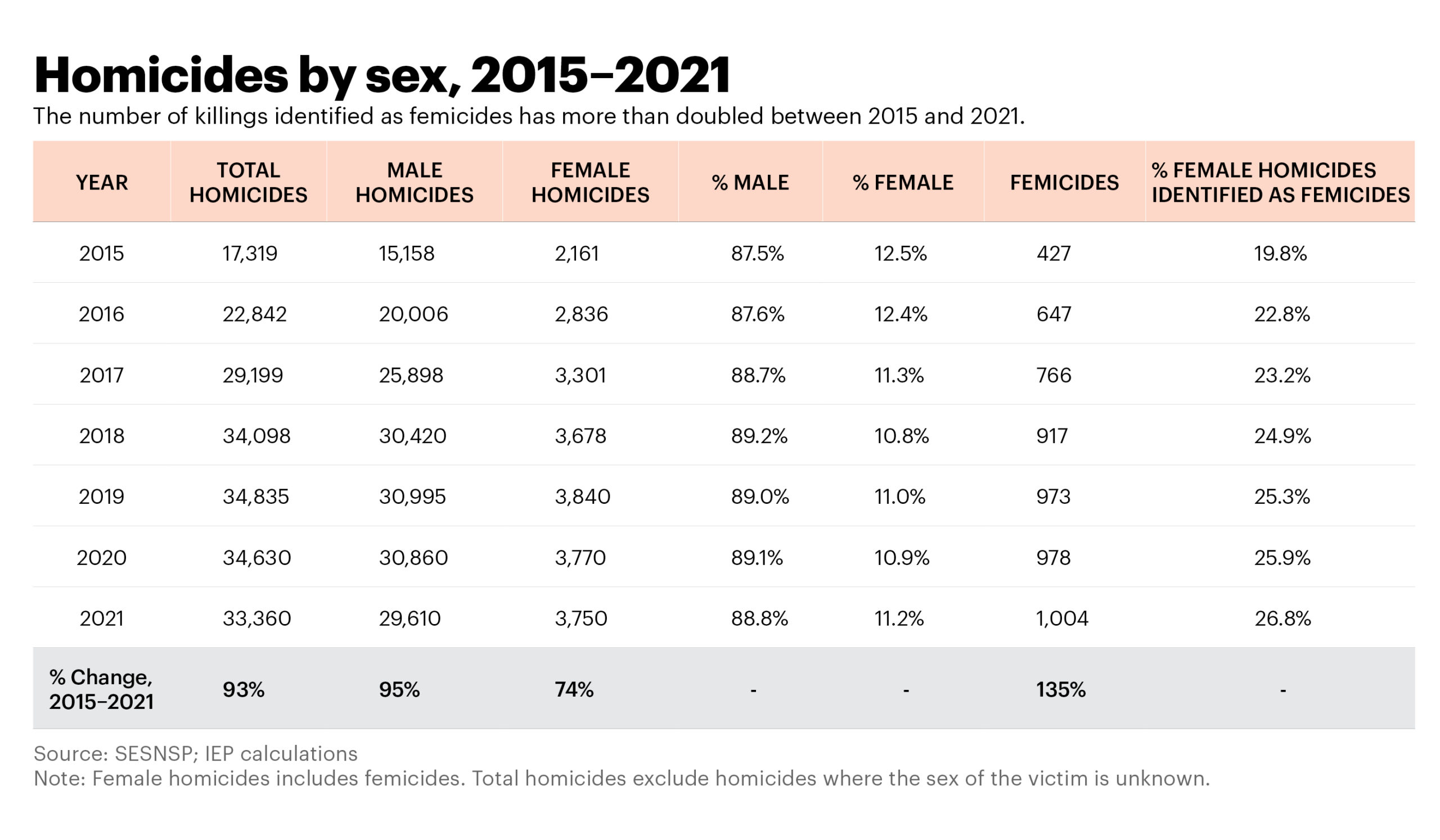

The incidence of femicide, or the murder of a woman for gender-based reasons, has risen significantly in recent years, from 427 reported victims in 2015 to 1,004 in 2021, marking a 135 per cent increase.[2] Femicides can be understood as a subset of female homicides: while femicides are usually included in female homicide figures, not all female homicides can be considered femicides. The proportion of female homicides identified as femicides has grown steadily in recent years. In 2021, more than a quarter of the 3,750 women killed in Mexico were classified as femicides.

Femicide is defined as the criminal deprivation of the life of a female victim for reasons based on gender. The murder of a woman or girl is considered gender based, and included in femicide statistics, when one of seven criteria is met. These criteria include evidence of sexual violence prior to the victim’s death; a sentimental, affective or trusting relationship with the perpetrator; and the victim’s body being displayed in public.

Femicide was first included in the Mexican penal code in 2012 and incorporated into official crime statistics as a distinct category in the same year. As a relatively new crime category that requires added levels of investigation and analysis to identify, femicides have not been uniformly classified as such by different law enforcement institutions since the category’s introduction. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the actual number of femicides in Mexico over time. However, the recorded rise in reported femicides is in line with increases in recorded family violence and sexual assault cases in Mexico over the past seven years.

Mexico became an international reference point for gender-based violence in the 1990s, following the murder of more than 370 women and girls in Ciudad Juárez in the state of Chihuahua. In 2007, the Alert Mechanism for Gender Violence against Women (AVGM) was first adopted. The AVGM allows citizens to request the declaration of a “gender alert” in municipalities where violence against women is increasing and obliges local authorities to examine the situation and implement measures to end gender-based violence. As of October 2021, 25 AVGMs have been declared in 22 of Mexico’s 32 states.

Several high-profile femicides in early 2020, including the killing of a minor, sparked major demonstrations against gender-based violence across Mexico. There were at least 359 demonstrations of this kind in 2020 and 239 in 2021, with protests peaking around March each year. For the past three years, annual marches have been held to mark International Women’s Day on 8 March. In addition, tens of thousands of women have participated in nationwide strikes to protest the epidemic of violence against women in Mexico.

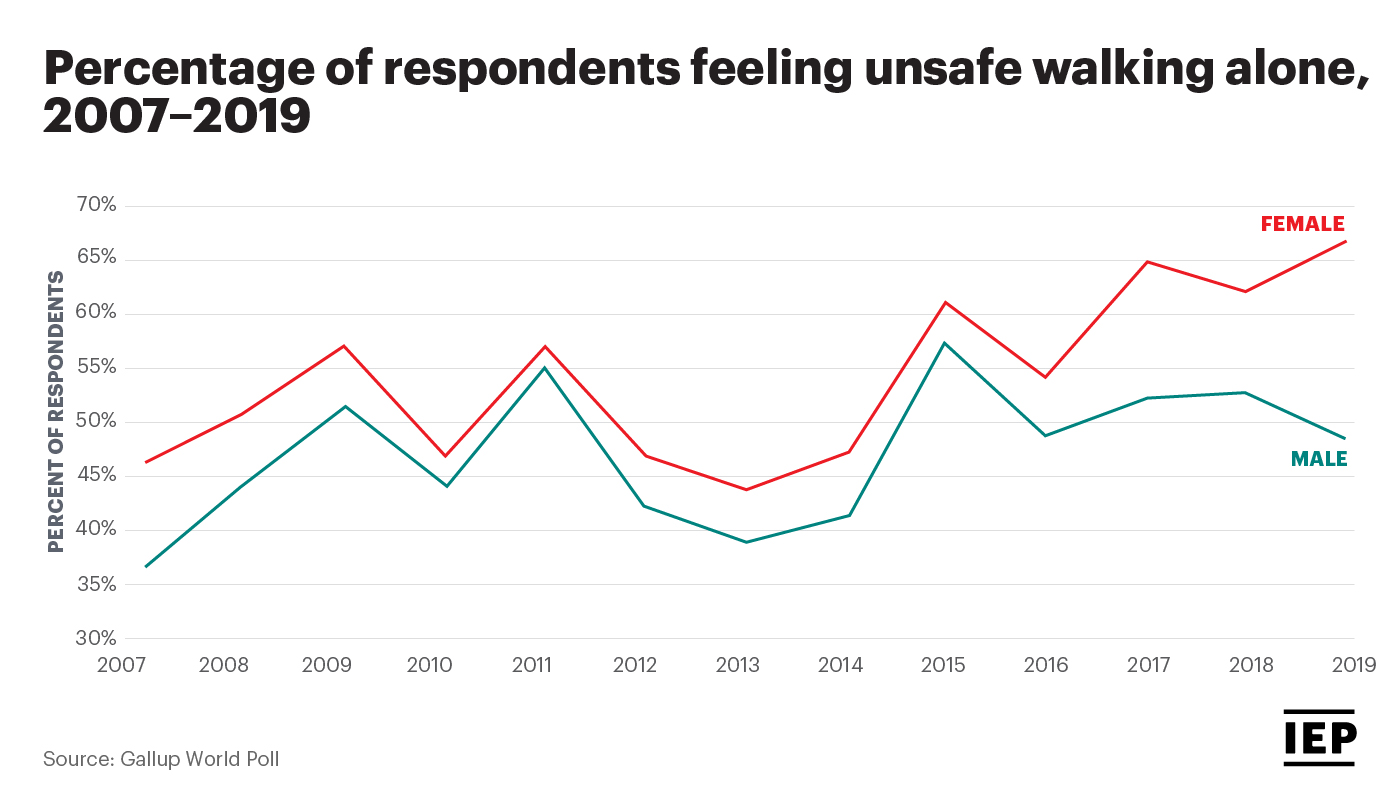

The growing prevalence of gender-based violence in Mexico has been accompanied by deteriorating perceptions of security. According to the Gallup World Poll, women in Mexico are more likely to say that they do not feel safe walking alone at night. While the perceptions of security for both men and women have deteriorated since 2007, the divergence in recent years has become increasingly stark. In 2007, 46 per cent of women reported feeling unsafe walking alone compared to 37 per cent of men. By 2019, this gap had widened significantly, with 67 per cent of women feeling unsafe compared to 48 per cent of men. This growing discrepancy between male and female perceptions of safety follows deteriorations in the rates of femicide, family violence and sexual assault since 2015.

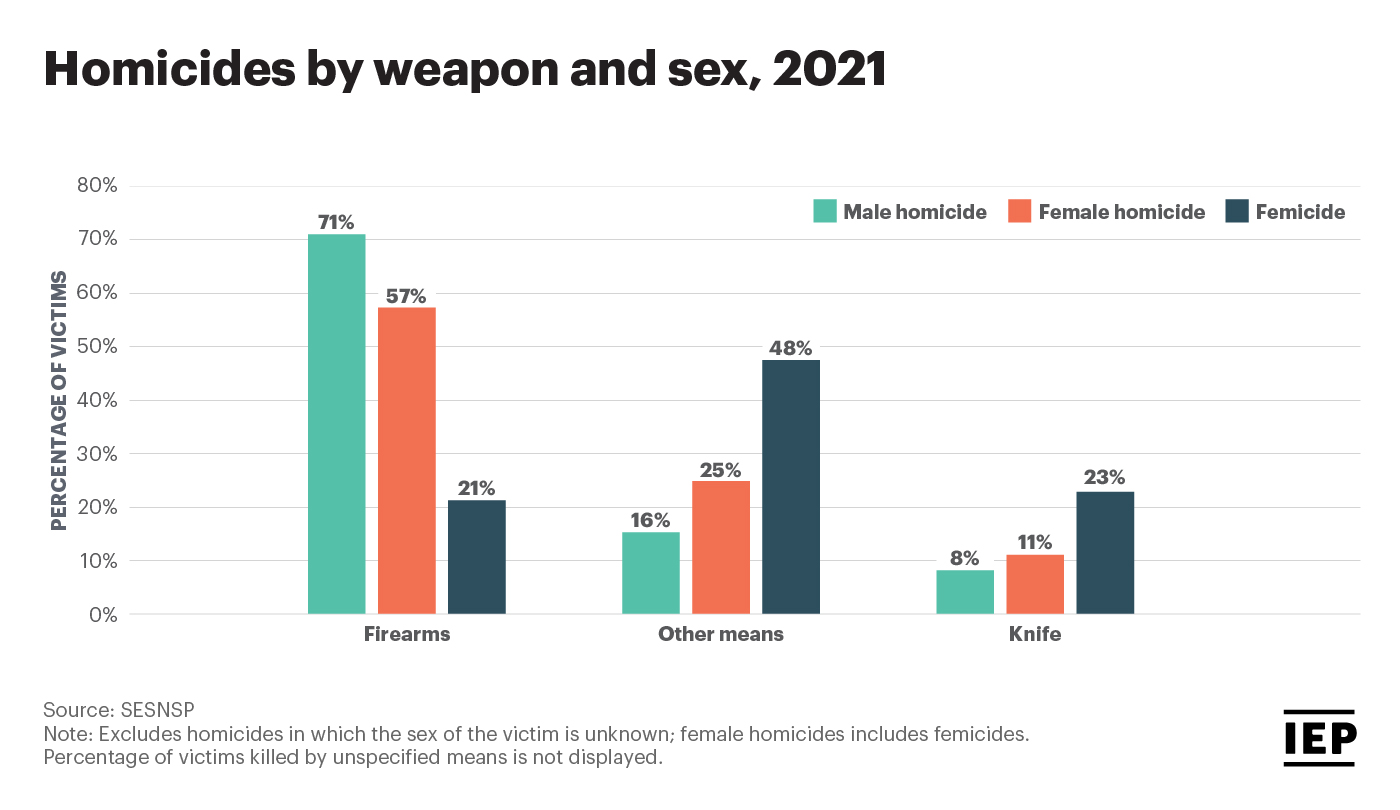

Based on available data, the 2022 MPI compares the dynamics of femicide to male homicide and overall female homicides. IEP’s research shows that firearms were the leading cause of death for both male and female homicides. Between 2015 and 2021, the absolute and relative numbers of firearms homicides increased substantially for men and women. The total number of male victims of homicides with a firearm increased by 229 per cent, while the total number of female victims increased by 261 per cent. During the same period, the proportion of male homicides committed with a firearm rose from 60.9 per cent to 71.3 per cent, while the proportion of female firearm homicides rose from 37.8 per cent to 56.8 per cent.

These numbers show that guns have become the primary means of both men and women being killed by homicide in Mexico in the past seven years. However, the same cannot be said for femicide victims, who are more likely to be killed by “other means”. Though official data does not provide additional detail, these cases include strangulation, drowning and suffocation. Knives were used in 23 per cent of femicides, while firearms deaths accounted for 21 per cent of femicides. While femicide is often discussed in the context of Mexico’s increasing homicide rate, there is a weak statistical relationship between femicide and organised crime (r=0.09) and between femicide and gun violence (r=0.24). This suggests that femicide is a national issue that is related to, but not dependent on, the upsurge of violence which has driven high levels of male and female homicide.

The age profiles of male and female homicide victims and femicide victims also provide important insight into the phenomenon. Of the three categories, victims of femicide are more likely to be minors (those under 18 years of age), accounting for 11.6 per cent of all victims. In contrast, minors account for 6.9 per cent of total female homicides and 3.6 per cent of male homicides.

Moreover, over the past seven years, the killing of minors has been on the rise for both girls and boys. Between 2015 and 2021, the number of girls killed rose from 243 to 275, with the number of such killings identified as femicides more than doubling in that time. As for boys, 574 were killed in 2015 and 911 were killed in 2021, a 58.7 per cent increase. In recent years, the upsurge of killings of minors as well as young adults has become so significant that homicide has become the leading cause of death of Mexican males and females aged 15 to 35.

Current data on femicide reveals a distinct type of violence which is not entirely explained by the overall increase in organized crime activity or gun violence in recent years. However, more work is needed to improve femicide data to truly understand the magnitude of femicide in Mexico, and how this type of violence differs from other homicides. In the future, this information will be critical to guiding tailored, evidence-based approaches that address distinct patterns of violence affecting men and women.