A complex web of economic shocks is threatening to unravel the already precarious stability of the world’s most violence-affected countries. These nations face a dangerous trifecta — limited trade access, high debt exposure and declining development assistance. In states already at the bottom of the Global Peace Index (GPI), the risks are not only economic but existential.

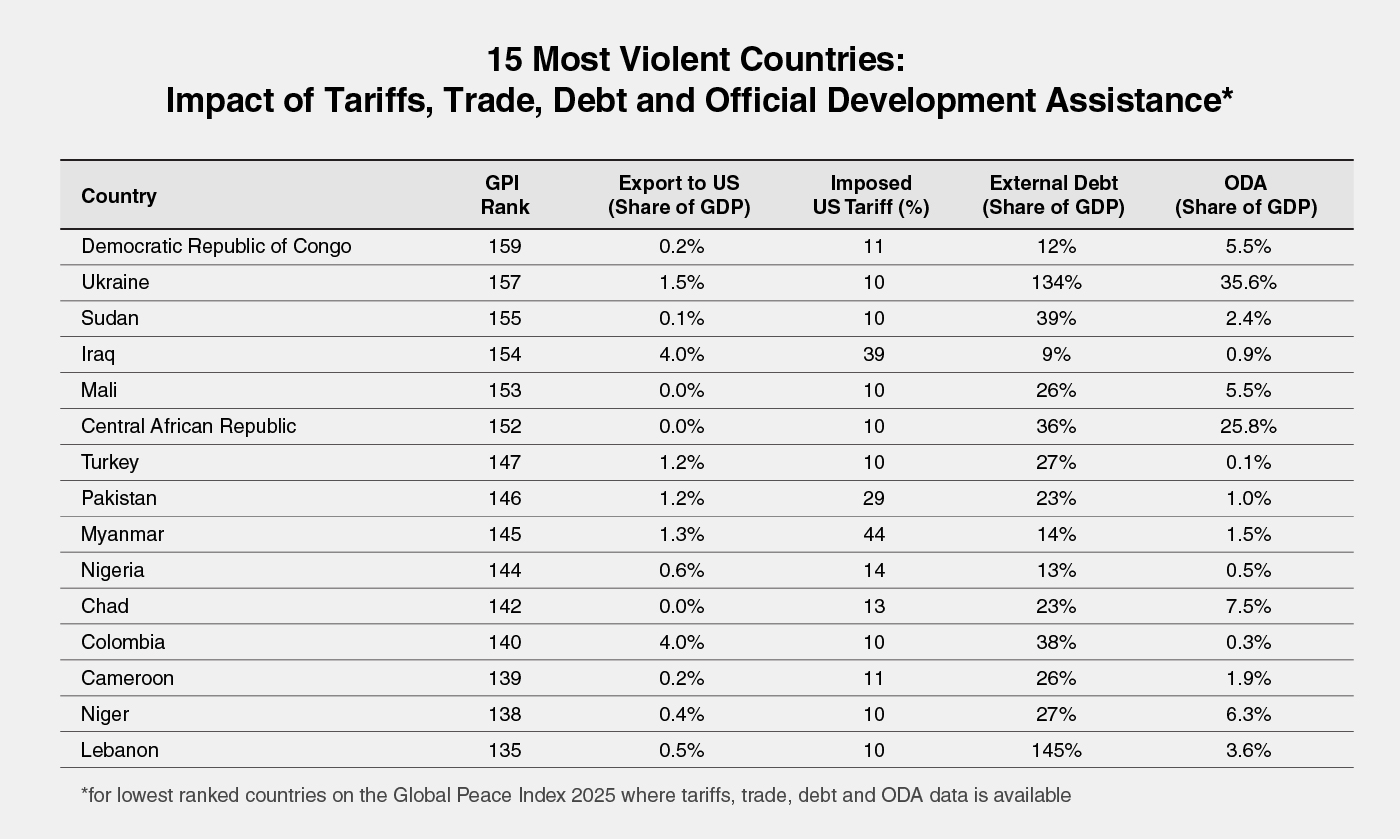

For the 15 most violent countries for which data on tariffs, trade, debt, and Official Development Assistance (ODA) are available (hence there are some gaps), many are grappling with rising US tariffs that restrict access to critical export markets. Myanmar, Iraq and Colombia, for example, face very steep tariffs, with exports to the US accounting for a significant share of their GDP. Although they may find substitute markets for their exports in the mid to long term, in the short term they can still face serious economic shocks.

At the same time, external debt burdens in some countries are extraordinarily high, as detailed in the Official Development Assistance report from IEP. Lebanon carries debt equal to 145% of its GDP, the highest among the group, while Ukraine follows closely at 134%. Some of the most violence-affected countries are taking on debt that may be unsustainable in the long run. These loans introduce future repayment obligations into already fragile fiscal systems, placing pressure on governments to divert resources away from basic services. Furthermore, countries such as the Central African Republic and Ukraine rely heavily on development assistance. They are followed by several others where such assistance constitutes a sizeable share of GDP, according to 2023 data. Given recent announcements of immediate and future international aid cuts by major donors, these countries are likely to bear the brunt of the reductions.

The convergence of constrained trade, rising debt and shrinking access to development assistance creates a feedback loop of fragility. As governments lose access to reliable revenue, whether from exports or concessional finance, it erodes their ability to fund core services, pay public employees or invest in economic recovery. In volatile settings, these gaps in governance can quickly become openings for unrest, informal control or conflict.

In countries where violence is already entrenched, the cumulative impact of economic constraints is especially severe. Weak institutions, ongoing insecurity and large youth populations create conditions where even modest economic shocks can have destabilising consequences. When development assistance becomes harder to access or repay, and trade opportunities shrink, fragile states are left with few options for recovery.

Without meaningful international coordination, these trends risk pushing the most unstable countries further into crisis. The erosion of economic resilience, layered on top of protracted conflict, threatens to undo years of development progress and deepen cycles of insecurity.

Economic decisions made at the global level, such as tariff regimes, loan conditions or aid allocations, often neglect their downstream impact on peace and stability. In fragile states, this oversight can be devastating. Policies that may appear fiscally prudent in isolation can, in combination, undermine core state functions and feed unrest.

A conflict-sensitive economic approach is urgently needed. Trade policy should incorporate humanitarian exemptions or preferential terms for violence-affected countries. Development finance must rebalance towards grants, particularly where repayment capacity is clearly limited. Debt relief should be accompanied by long-term planning and institutional reform to avoid perpetuating cycles of dependency.

There is precedent for coordinated action. The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative in early 2000s showed that strategic debt forgiveness, when paired with investment in public services, can improve both economic and social outcomes. Today’s crisis calls for a similarly bold and collaborative response.

Countries facing the dual burden of violence and economic fragility require more than short-term fixes. Without coordinated, peace-oriented policies from the international community, the world’s most unstable nations risk being pushed even further toward crisis, with consequences that will extend far beyond their borders.