Geopolitical risks today exceed levels seen during the Cold War, driven by heightened military spending, stalled efforts at nuclear disarmament, and a diminished role for multilateral institutions like the United Nations.

Unlike the bipolar structure that prevailed in most of the 20th-century Cold War, the current global landscape is shaped by technological dominance, economic interdependence, and influence competition across emerging regions such as Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. While China’s rise is clear, emerging regional powers, such as Brazil, Türkiye, United Arab Emirates, South Africa, and Indonesia are also seeking to shape regional and global dynamics.

The proliferation of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and 5G infrastructure has transformed power dynamics, with states vying to secure strategic dominance in these areas. Meanwhile, economic interdependence, once seen as a stabilising force, is increasingly weaponised, as seen in trade wars, sanctions, and the deliberate decoupling of supply chains in critical industries. These dynamics are exacerbated by the intensification of proxy conflicts, hybrid warfare tactics, and disinformation campaigns that further destabilise global alliances and erode trust among nations.

During the Cold War, developing countries became arenas for proxy wars, economic exploitation, and political interference, exacerbating instability, poverty, and underdevelopment. Today, as global power struggles intensify, nations in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia risk becoming similarly entangled, facing increased economic pressures, disrupted trade partnerships, and reduced access to critical investments. Debt servicing costs now outweigh investments in essential services for many developing countries, undermining their capacity for sustainable growth. Competition for influence among powerful nations may undermine local governance and development priorities, diverting attention from urgent challenges such as climate change, food insecurity, and peacebuilding.

Also read: How rising developing nation debt could reshape the world

The number of countries with significant influence in more than five other nations has almost tripled, rising from 13 at the end of the Cold War to 34 in 2024. In addition to China and India, countries like Türkiye, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, South Africa, Brazil, and Indonesia are all growing in influence.

The Trends in Geopolitical Influence and Peace report from the Institute for Economics & Peace provides a critical analysis of ongoing trends in international affairs, amidst growing discussions of major conflict and frequent assertions that the world has entered a new Cold War. Currently, there is an observable trend of major global alliances solidifying, with Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran strengthening formal pacts, while NATO allies are now exceeding their two per cent of GDP commitments to defence spending.

Military spending is now at its highest level since the end of the Cold War, with a notable increase since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war. The idea that the world is in a new Cold War arises from a series of escalating geopolitical events that reflect intensifying rivalry among major powers, particularly the United States and China. Proponents argue that growing ideological, economic, and military competition mirrors the Cold War dynamic, with spheres of influence and proxy conflicts re-emerging as they did through US-Soviet rivalry. Tensions have mounted over trade disputes, military build-ups in the South China Sea, and competition for technological dominance. Russia’s actions, including its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, have further polarised global alliances and prompted NATO to expand and reassert its role in European security.

Also read: Europe’s call to arms: a shift towards military self-sufficiency

Simultaneously, ideological divides have deepened, with authoritarian regimes like China and Russia promoting alternative governance models in opposition to liberal democracies. These developments, coupled with the rise of strategic decoupling and a resurgence of proxy conflicts in regions like Africa and the Middle East, evoke parallels to the Cold War era of bipolar competition, though now in a more interconnected and multipolar global context.

While there are parallels to the Cold War, the contemporary international system differs significantly in key areas such as trade, interdependence, the rise of emerging powers, and global mega trends like climate change and cybersecurity. These shifts highlight the need for nuance in “new Cold War” debates, rather than absolute comparisons.

Powerful states compete for influence in smaller countries. In cases of countries in conflict, this can manifest through competitive interventions in civil war. In most cases, however, this can be through increased aid, trade, or defence agreements. Understanding contemporary geopolitics becomes more accessible with datasets like Foreign Bilateral Influence Capacity (FBIC), which measure the level of competition for influence. The FBIC quantifies bilateral relationships by assessing a country’s capacity to project influence through economic, political, and military indicators to identify power dynamics, detect shifts in influence patterns, and understand the nuanced competition between states. Most great powers or even regional powers dominate in their own immediate zone of influence.

Examining two distinct regions, West Africa and South Asia, reveals contrasting dynamics. While China’s rise is evident in both, West Africa has seen China emerge as the dominant external state actor with minimal competition. In contrast, South Asia has experienced significantly greater competition for influence. Since 2000, French influence in West Africa has fluctuated significantly, with sharp spikes and declines, while China has shown steady growth, becoming the dominant power. Around 2011, China overtook the US, whose influence has declined sharply since. China’s growing dominance is driven primarily by economic interests, including substantial investments in mining, agriculture, and telecommunications.

Since 2000, South Asia has seen significant increases in the proportion of influence held by regional and global powers India, China, and the US. The region is subject to significant geopolitical competition, with China’s growing influence manifesting in initiatives like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Under the Belt and Road Initiative, China has financed ports, highways, and energy infrastructure, securing access to the Arabian Sea. Partnerships with countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh have further expanded. India and the US have both increased investment and strategic interest in South Asia, with India often in direct competition with China and Pakistan and the US also seeking to counter Chinese influence.

During the Cold War, global influence was majorly shaped by the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, with significant impacts observed in regions critical to their strategic interests. High levels of competition are evident in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and across parts of South and Southeast Asia, specifically in India, Myanmar, and Indonesia, largely due to geopolitical and military positioning, as well as their control of key trade routes. MENA, with its vast oil reserves, became a key arena for superpower involvement, where both the US and the Soviet Union sought to influence political transitions and control resource-rich territories. Similarly, Southeast Asia saw the US and Soviet Union exerting influence to sway political outcomes, often supporting opposing factions in countries that were of strategic importance for military and trade purposes.

During the post-Cold War period, the global landscape of geopolitical competition shifted significantly. Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the East and Southern regions, emerged as a key region of high competition, driven by the reduced bipolar structure of the Cold War and the increased involvement of a range of external actors. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a unipolar moment emerged with the US as the predominant power. Over time, new players including China, regional powers, and multinational organizations began competing for influence, while traditional powers like France worked to maintain their standing. This competition was fuelled by efforts to secure access to natural resources, such as oil and minerals, and to shape political outcomes in the wake of internal conflicts and state fragility across the region. The resulting environment saw multiple powers actively engaged in providing aid, investment, and military support, marking a departure from the Cold War’s concentrated rivalries and illustrating a more competitive global order.

External competition significantly impacted the Syrian Civil War. Support from Russia and Iran allowed the Assad regime to survive and achieve victory before its dramatic collapse in December 2024. Russia and Türkiye solidified their positions as the most influential states in Syria as of 2024. Meanwhile, countries unwilling to support the Assad regime, such as Germany, lost what was once significant influence. Syria also shows the unstable nature that external influence competition can have on conflict. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with Iran’s and Hezbollah’s conflicts with Israel, made both parties hesitant to increase their support for the Assad regime. This reluctance coincided with multiple rebel offensives that eroded the regime’s previously stable control over much of the country. Türkiye, meanwhile, is likely to build on its influence given its support to several of the more powerful factions now ascendent in Syria.

In the past decade, the landscape of geopolitical competition has continued to evolve, with high levels of competition emerging in the Sahel. The Sahel’s high competition arises from external and regional actors vying for influence in a context marked by instability and resource scarcity. Foreign powers, local governments, and non-state actors all strive to shape political and security outcomes through military interventions, development aid, and political alliances, contributing to a complex and contested environment. There is also significant competition in Peru, Brazil, India, and Southeast Asia. In India, growing economic and military power has positioned it as a key player in the Indo-Pacific, balancing relationships with the US and China. As India strengthens ties with the US and its allies, particularly through frameworks like the Quad, it faces competition from China, which seeks to expand its influence, especially through the Belt and Road Initiative and in the Indian Ocean. In Brazil, regional competition is driven by its leadership in Latin America, economic power, and strategic role in global institutions like BRICS. Its growing influence, particularly with China and other emerging economies, has heightened rivalry with the US and other Western powers over economic and political alignments. Peru’s competition arises from its rich natural resources, especially in mining and energy sectors, making it a focus for external actors, particularly China.

Also read: Nigeria’s BRICS Partnership – A New Chapter in a Multipolar Moment?

More states are now exerting higher levels of influence in more countries than at any other point in history. The number of countries exerting more than 10 per cent influence in five or more countries has increased significantly over time. In 1960, only five countries reached this level, but today there are 34. This trend reflects the overall rise of middle powers, though some of the increase is likely attributable to European Union enlargement rounds in 2004 and 2007.

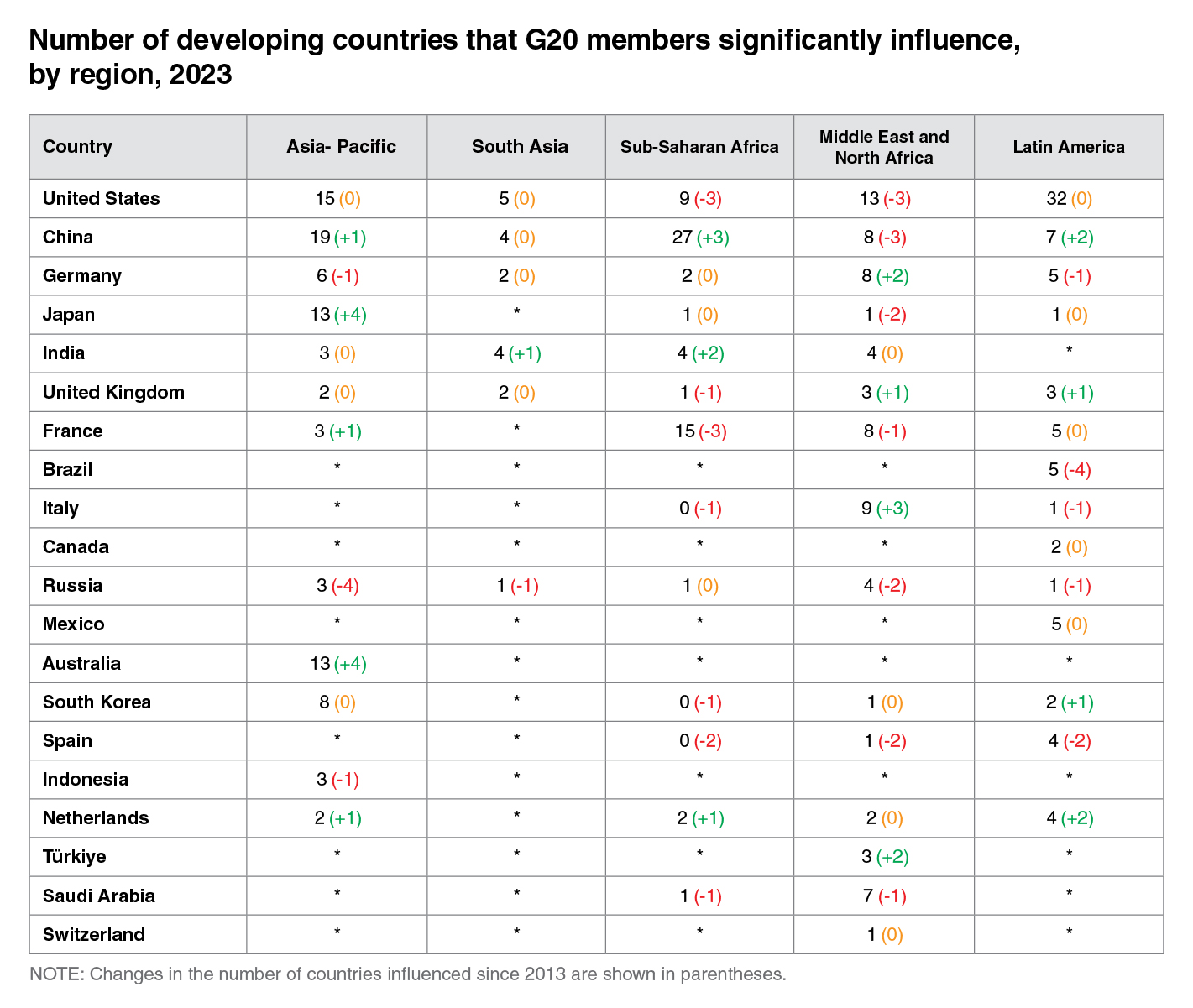

Overall, where one powerful state gains influence in one region it is offset by losses elsewhere. This reflects the absolute levels of power and influence any one powerful state can project and the limitations of even powerful or rising states. The two largest powers, the US and China, are dominant, but with different zones of largest influence. The US has above 10 per cent influence in 74 LMICs, while China has it in 65. While both states have similar levels of influence in the Asia-Pacific, there are significant deltas in influence elsewhere, with China holding influence in 27 sub-Saharan African states compared to nine for the US, and the US dominating Latin America with 32 states compared to China’s seven. In this metric at least, there is also relative stability with the status quo being a very common result. Across all regions, the largest increase for a single country influencer was a six-state gain by China, and the largest loss of influence was eight states for Russia.

Apart from the two largest powers, most major economies tend to concentrate their influence on a single region or focus predominantly on one area. Brazil, Australia, Mexico, Canada, Indonesia, Türkiye, and Switzerland only hold influence in one region, and with the exception of Canada and Switzerland, that influence is exerted within its own region. It illustrates that absolute levels of influence also provide a perspective that extends beyond headlines about particular countries gaining influence, such as through arms distribution. It also likely points towards growing influence beyond the top 20 economies and likely less dependency for most states on one or several powerful allies.