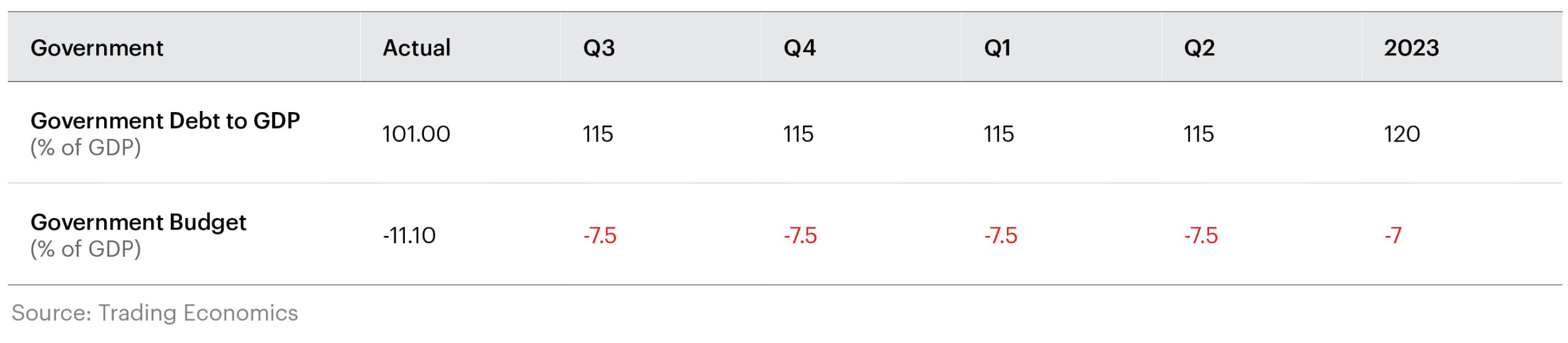

In May of this year, for the first time in its history, Sri Lanka defaulted on its debt. Sri Lanka is currently in the midst of its worst economic crisis in over 70 years and the government has all but collapsed. Rocketing fuel prices have caused queues that can last for days as well as the collapse of many public services, with food shortages leaving thousands of Sri Lankans hungry. Government debt as a percentage of GDP is now 101% and this is projected to rise to 120% by 2023.(1)

The knock on effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis in Ukraine have been well documented. Rises to food, fuel and commodity prices have triggered particularly intense shocks to countries with low levels of societal resilience. Globally, food insecurity is on the rise and is projected to increase by 43% by 2050.

However while the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have both wreaked havoc on the global economy, the issues facing Sri Lanka cannot be solely blamed on these factors. The situation has been exacerbated by a number of unique domestic factors, which must be identified if we are to truly understand how Sri Lanka arrived at this position.

As 2022 began the situation in Sri Lanka appeared bleak, with inflation rates soaring and commodity prices rising to unprecedented levels. The World Bank estimated that over 500,000 people in Sri Lanka had fallen below the poverty line. The country was experiencing food, medicine and fuel shortages as well as daily blackouts and an economy in freefall.

In response to this deteriorating situation, then president Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared an economic emergency, authorising the military to regulate the prices of essential items. These actions did little to ease the crisis and March 2022 saw the beginning of nationwide anti-government protests and counter-protests that led to a number of deaths and injuries. The protesters accused the government of gross economic mismanagement and contributing to the crisis.

Despite a significant response to the initial protests by police and security services, protests continued in Sri Lanka. By mid-July, after months of instability, Sri Lanka’s government all but collapsed, with the President resigning and fleeing to Singapore. The then Prime Minister and acting President, Ranil Wickremesinghe (who was formally elected President later on 21 July), declared a state of emergency and imposed a curfew in an attempt to quell the protests. However the protestors subsequently seized the presidential office and demanded Wickremesinghe’s resignation.

Sri Lanka already ranks 136 out of 163 nations in the 2022 Global Peace Index (GPI) for its violent demonstration score. However, Sri Lanka is predicted to fall further in ranking in the 2023 GPI as a result of the widespread demonstrations in 2022.

The Rajapaksa governments have dominated Sri Lankan politics for two decades and have been characterised by widespread accusations of financial mismanagement, corruption, nepotism and authoritarianism.

2009 marked the end of a brutal 30-year civil war in Sri Lanka and there was hope that this could mark a new era for the country. In order to rebuild the country following the conflict, Sri Lanka relied on significant foreign loans. Sri Lanka currently owes foreign lenders over $51 billion, with particularly large debts to China (10%) among others and no viable route to honouring these debts (2).Due to the failure of the Sri Lankan government to pay previous debts with China, a strategically important port within Sri Lanka was given to China on a 99-year lease.

There was also a lack of investment in foreign trade following the conclusion of the civil war. The Sri Lankan government instead focussed on providing goods to its domestic market, importing $3 billion more than the country exports each year. This reliance on imports on the back of rising commodity prices has been a catastrophe for the Sri Lankan economy. Fuel imports made up 20% of inbound shipments in December and the price jumped by 88% from the previous year (3).

The government has also been accused of undertaking massive vanity infrastructure projects, such as the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport or the Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium, both of which see almost no operational usage and generate no revenue despite costing the country billions. These types of projects were often financed by further unsustainable loans from China, and occurred at the same time as the Rajapaksa governments carried out massive tax cuts and agricultural policies that further cut revenue.

In April 2021, President Rajapaksa announced an immediate ban on fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides. These actions decimated the crops of Sri Lankan farmers and contributed to what was an already growing food shortage. The ban was later reversed, however there was still a substantial drop in crop yields across Sri Lanka, as the majority of fertilizers failed to make it to farmers in need of them. This further spiked the cost of agricultural produce within Sri Lanka, forcing the already in debt government to rely on increased imports of grain from neighbouring countries. It is the intersection of these unsustainable and ineffective economic policies that has left the Sri Lankan economy extremely vulnerable to shocks.

There is no clearer example of economic vulnerability within Sri Lanka than the collapse of the tourism industry. Sri Lanka’s economy has been extremely dependent on tourism and this has been undermined by a number of factors.

Following the conclusion of the civil war there was a massive investment in the economy aided by a number of international loans. One sector that received particularly significant investment in an effort to boost growth was the tourism sector. This critical sector of the Sri Lankan economy, that accounts for over 12% of GDP, was left reeling from a number of deadly terrorist attacks – including an incident on Easter Sunday 2019 that left over 250 dead and 500 injured and directly impacted the number of travellers.

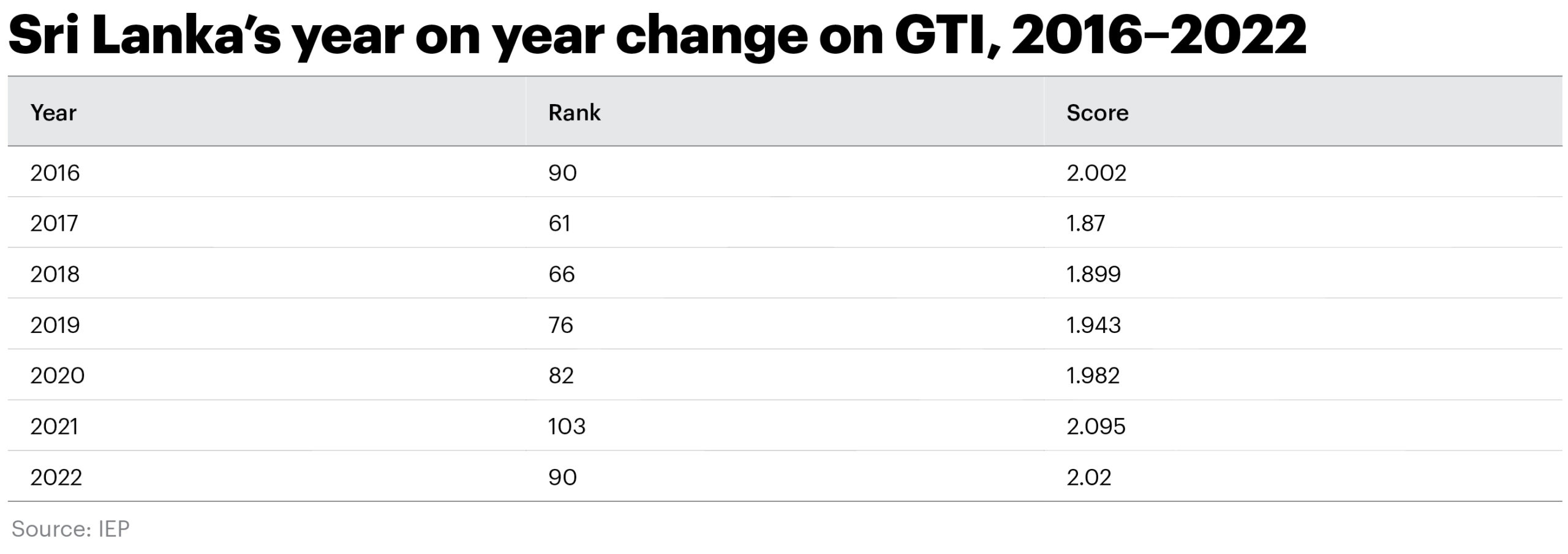

Sri Lanka was ranked 104 out of 161 in the Global Terrorism Index (GTI) in 2016, however a number of deteriorations saw it rise as high as 18 following the 2019 attacks. Sri Lanka remains high on the GTI and is currently the 27th most impacted country by terrorism.

In 2019, before the attacks occurred, tourism was worth $5.61 billion to the Sri Lankan economy, however in 2020 this fell to $1.08 billion (4).

On the back of this, the COVID-19 pandemic almost entirely shut down Sri Lanka’s tourism industry before it had a chance to recover. As the industry began its post-COVID recovery, the Russian invasion of Ukraine further decimated the sector. Up to 30% of visitors to Sri Lanka last year came from Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Belarus; and the events in Ukraine are likely to drastically lower that figure going forward (5). This triple whammy of factors has hamstrung the tourism sector in Sri Lanka and the sector shows little sign of growth.

It will be a long road to recovery in Sri Lanka. The country currently needs billions of dollars every month to import food and fuel, despite being bankrupt and having almost no foreign currency reserves. The IMF is hopeful that bailout talks can recommence soon, however until it has a functioning government Sri Lanka is unable to develop an economic recovery plan and prove that its debts can become sustainable.

Although the economic situation in Sri Lanka is bleak, it is not the only country facing serious economic obstacles. Rises to interest rates and inflation, paired with devaluing currencies, is an enormous problem for other countries in the region as well as further afield. Sri Lanka was unable to navigate these economic shocks due to its extremely low resilience. It is vital that countries with a high level of debt that are facing similar economic headwinds evaluate their responses to these issues and learn from these threats.