Since the implementation of constitutional reform a little over a decade ago, Myanmar has existed in a ‘quasi-democratic’ state that many in the international community hoped would signal the beginning of a transition to a stable democracy. However that fledgling hope was crushed following the most recent general election on 8 November 2020.

With the February 1 ousting of the newly elected officials, the abrupt return to military rule triggered a movement of peaceful pro-democracy demonstrations. These quickly evolved into waves of general strikes and other acts of civil disobedience. Civilian opposition has steadily increased, and is now on the receiving end of a severe and vicious campaign of repression by the Burmese military.

As of 14 February 2022, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners reports that an estimated 1549 people have been killed. This has accompanied 12,143 recorded arrests, with a further 1,974 arrest warrants issued. In IEP’s most recent Global Peace Index, Myanmar fell to a ranking of 131 out of 163 countries in terms of societal peacefulness. International observers say that the country is now on the verge of civil war.

It is within this precarious geopolitical context, that IEP ran a series of remote Positive Peace workshops for Burmese peace activists working both internationally and on the ground in Myanmar. Running from November 2021 to December 2022, these workshops sought to enable the pursuit of a sustainable, local peace by providing select community leaders with the knowledge and tools needed to create and understand Positive Peace.

Despite an original plan for face-to-face workshops, the onset of Covid-19 and the rapid deterioration of conditions in Myanmar necessitated a shift to a remote workshop format. Due to the ever-present risk of reprisal or persecution by the Burmese military, this raised serious cybersecurity concerns. IEP took this responsibility extremely seriously, and set out to ensure a safe and secure environment for all participants.

A range of cybersecurity measures were implemented, including a ban on the recording of sessions, as well as allowing participants to keep cameras turned off and encouraging the use of pseudonyms if needed. With these measures in place, our participants were able to speak openly and bravely about the reality of living under the oppression of the junta.

The workshops were held for a group of just under 25 passionate Burmese women and youth leaders, each united in their desire to contribute to the building of a sustainable peace in Myanmar. Among the organisations represented by participants were the Democracy, Peace and Women Organisation (DPW), and the Karen Women Union (KWU), amongst others. The DPW has recently been engaged in peaceful protests in urban and ethnic areas, whilst also strategically lobbying the international community in the aftermath of the coup – particularly concerning the military shootings of civilians, and the need for international sanctions on the military council.

An interpreter was invited along, and the sessions were presented simultaneously in English and Burmese.

As the workshops began, participants were first introduced to the research work of the IEP. A particular focus was given to Myanmar, and they were led through relevant research and key trends apparent in IEP’s core indices. Currently, Myanmar sits at a ranking of 131 out of 163 countries in IEP’s Global Peace Index.

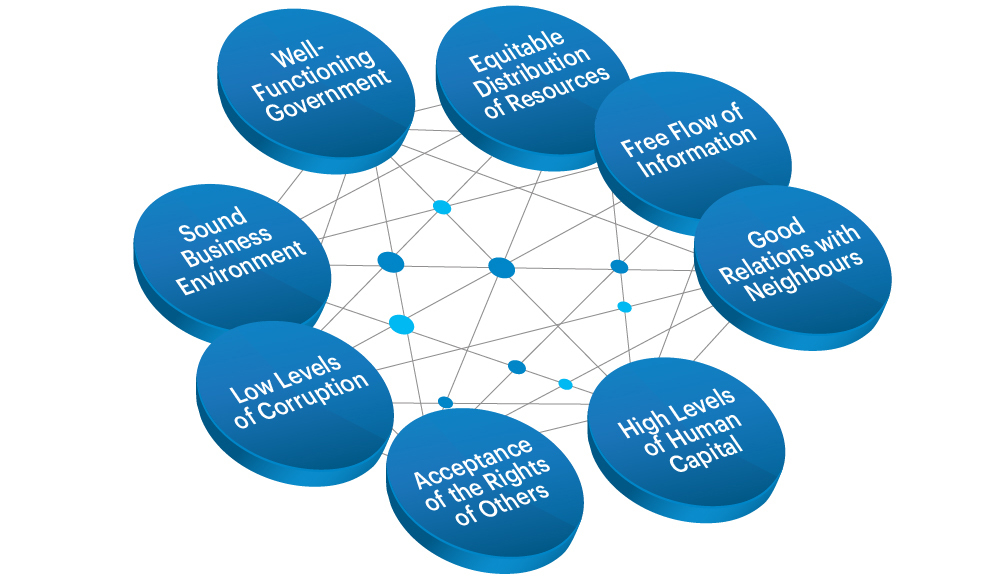

This was followed with an introduction to IEP’s Positive Peace Framework. Positive Peace is described by IEP as being comprised of the ‘attitudes, structures, and institutions’ that underpin a peaceful society. It is a systems-based approach which is measured through the strength of the eight Positive Peace Pillars. It stands in contrast to Negative Peace, which is defined as being simply the absence of violence. One participant explained the necessity of this more nuanced approach, writing that “authorities, government and military need to understand positive peace so that they can apply it in the community”.

Equipped with this new awareness of Positive Peace, the Burmese community leaders were then led through a mapping exercise activity. Participants were asked to identify how each of the eight Positive Peace pillars applied in their own political and social context. Close attention was paid to areas of weakness and potential improvement. Through this, they were encouraged to begin to apply the Positive Peace Framework in their own communities as a tool for measuring and building peace. Examples identified by participants include weaknesses in the pillar representing the Free Flow of Information, with Myanmar having a severely inadequate connection to internet and limited journalistic freedom.

This was all part of the process of capacity building, and at the conclusion of the initial round of IEP workshops, the Burmese community leaders were tasked with a practical application of the Positive Peace Framework. This involved the design and implementation of a locally based project to activate peace in their own communities.

One standout example of a project conducted by one of our Burmese peace leaders was a two-day, face-to-face educational seminar for a class of business students. Gathering in the jungle, the class brought together students who are largely displaced and living in camps, with the aim of sharing knowledge and resources on IEP’s Positive Peace Framework.

Focusing on the pillars of Sound Business Environment and the Equitable Distribution of Resources, the students were led through a discussion of the ways in which the pillars were applicable to their own communities. Topics of conversation ranged from a desire for no more air strikes, to the need for better connection with the outside world. Students highlighted the difficulties of having little internet connection, on top of the rarity of opportunities for education, research, and publication.

The importance of these interactions was summarized by the organizer, who wrote that “discussions and sharing with each other can assist the students’ abilities not only to improve their presentation skill but also in confidence and in building hope”.

The successful results of this project were shared with the remaining cohort of Burmese women and youth leaders at the final IEP Positive Peace workshop held in February 2022. Other projects are still ongoing, and now that the participants have been equipped with the necessary knowledge and practical tools, they have been empowered to continue building peace in their own communities.

It is hoped that by activating peace in this manner on the local scale, it will gradually have a knock-on effect internationally. A positive outcome of the workshop was that two participants have applied to participate in the 2022 IEP Ambassador program.

IEP would like to thank the Emalyn Foundation for providing the funding to conduct this series of Positive Peace workshops with our group of Burmese community leaders and peacebuilders. It is important to spread the word about IEP’s work, and in the words of one of our participants, “everyone must understand … Positive Peace, so that we can build a more sustainable way of peace building for our society and our country”.

If you are inspired by this story of some of our incredible IEP Peace Ambassadors, expressions of interest for our upcoming April 2022 Peace Ambassador cohort are open now.