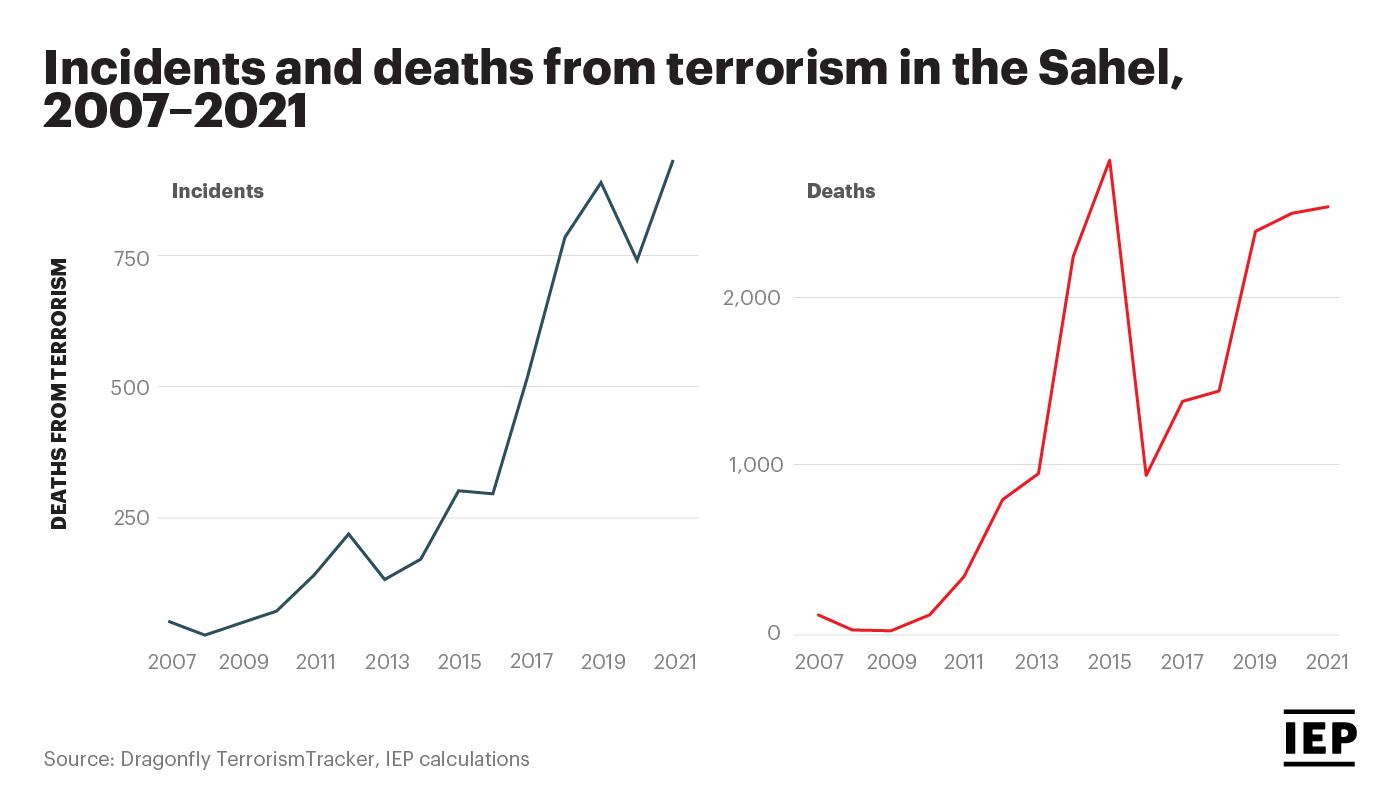

The Sahel region faces many converging and complex social, economic, political and security challenges. The inability of several Sahelian governments to provide effective security has encouraged terrorist groups to continue their activities, making the Sahel increasingly more violent, with deaths rising ten times between 2007 and 2021.

The Sahel is home to the world’s fastest growing and most-deadly terrorist groups. Groups such as Islamic State (IS) continue to wage a violent campaign in the region, with deaths in the Sahel accounting for 35% of global total of terrorism deaths in 2021, compared with just 1% in 2007.

Thus far, international and regional responses to the violence have failed to prevent rising levels of terrorism, made worse by the region having some of the highest population growth, significant increases in food insecurity and widespread displacement.

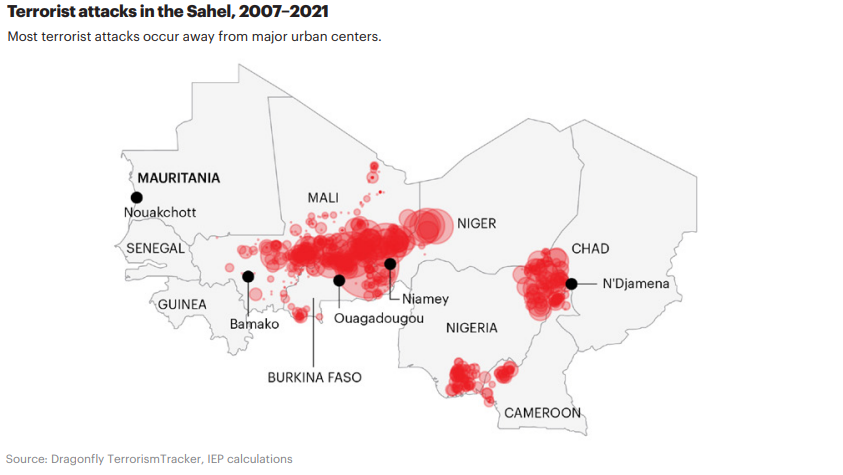

Deaths and incidents increased across every country in the region other than Mauritania and Chad, and every country in the Sahel other than Mauritania and Chad recorded at least 40 deaths from terrorism in 2021. Total deaths recorded in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in 2021 were 732, 574 and 588, respectively.

Niger had the largest increase in deaths from terrorism, with deaths more than doubling over the past year. This is the highest terrorism death toll in the country since 2007. Although the majority of deaths were attributed either to unknown groups or to unspecified Muslim extremists, it is suspected that these attacks could be the work of either Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA) or Boko Haram who were active in the country in 2021.

The rise in terrorist activity in Niger is part of a larger increase across the Sahel region, with similar surges seen in Mali and Burkina Faso over the past few years. One possible reason for the rise in violence in Niger is that Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’adati wal-Jihad (JAS) and ISWA appear to operate in those areas, whereas Ansaru seem to operate in Kaduna State, Nigeria.

There is also evidence of jihadi activity in the Cote d’Ivoire, aimed at fermenting religious and ethnic tensions. A small village along the border with Burkina Faso, Kafolo, had seen two major attacks in 18 months. Locals and the Ivorian government attributed the attacks to Fulani jihadis. The attacks led many Fulanis to leave the area, as they feared reprisals (adding to the already large displacement); and, second, it brought a large military presence which has discouraged villagers from going to the fields, as they fear being attacked.

Burkina Faso recorded 732 deaths from terrorism in 2021, its second highest number of deaths (scoring 8.270 on the GTI). Although the majority of deaths were attributed either to unknown groups or to unspecified Muslim extremists, it is suspected that these attacks could be the work of either ISWA or Boko Haram who were active in the country in 2021. There were 17 deaths attributed to Boko Haram and 349 attributed to ISWA in 2021. It is therefore unsurprising that Burkina Faso recorded the largest deterioration in peacefulness on the 2021 Global Peace Index (GPI), falling 13 places.

Mali in 2021 recorded its highest number of terrorist attacks and deaths since 2011. Attacks and deaths from terrorism in Mali increased by 56% and 46% respectively, when compared with the previous year. This is the largest year-to-year increase since 2017, continuing an upward trend that began with the 2015 declaration of a state of emergency in the wake of the Radisson Blu Hotel attack in Bamako.

Deaths in Nigeria fell by 51% in 2021, following three years of successive increases. This decline was due to a fall in deaths attributed to Boko Haram and ISWA, particularly in the Borno region where deaths fell by 71%. ISWA overtook Boko Haram as the deadliest terror group in Nigeria in 2021 and, with an increased presence in neighbouring countries such as Mali, Cameroon, and Niger presents a substantial threat to the Sahel region.

There are indications that terrorism activities are spreading westward, with some terrorist activity in Benin and Togo. One possible explanation for the increase in activity is groups looking to exploit internal political instabilities brought about by coups or attempted coups in several coastal countries.

A closer look at the data highlights that most attacks occurred in border regions, where governmental control is generally low and the military tends to operate out of fortified bases.

Terrorist activity has been primarily concentrated in the Lake Chad Basin, comprising parts of Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, and the Central Sahel area along the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger border.There is also evidence that the violence is encroaching on the coastal states, with some activities occurring in Benin and Togo

Counter insurgency has significantly decreased Boko Haram’s activities, with the organisation recording only 64 attacks in 2021. Deaths dropped by 92% from 2,131 in 2015 to 178 in 2021. The decline of Boko Haram contributed to Nigeria recording the second largest reduction in deaths from terrorism in 2021, with the number falling by 47% to 448.

One possible explanation for the decline of Boko Haram was the death of their leader Abubakar Shekau in 2021. Following the 2012 Tuareg rebellion, the occupation of Timbuktu by jihadis, and the establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Azawad, the international community, with the consent of the Malian government authorised the dispatch of a large French and African Union-led forces. The operations have had some tactical successes such as killing key leaders, although it did not prevent AQIM and JNIM from growing and expanding their operations.

In the Sahel, over the last few years, the terrorism environment has gone through several changes, as new groups emerged, other merged, adapting to the local, regional and international counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations.

This gave rise to what has been termed the ‘jihadisation of banditry as criminal groups look to use religion to defend their criminal actions. Some of the groups had chosen to join the al-Qaeda franchise or the Islamic State franchise, which may also explain the increase in violence.

With its challenging terrain, distinct local practices, and porous borders, local leaders in the Sahel have tremendous autonomy; they operate as political entrepreneurs, making calculated decisions as to where to operate, how, and against whom. They exhibit greater willingness to negotiate or shift allegiances, as their principal goal is survival.

This type of pragmatism is also present with those deemed as bandits, typified by the notorious Dogo Gide, a Nigerian bandit, known to cooperate with Ansaru, with the terrorists even supporting a raid against a rival gang. The implications for the security environment are substantial, as the head of a terrorist group may not be theologically wedded to the transnational jihadi networks.

This raises the prospect of a larger shift in jihadi strategic thinking in that historically, jihadis commitment to ideological purity meant that they weakened their ability to build and hold a state, but this pragmatic shift raises the prospect of sustained, low-intensity conflict that would facilitate a takeover sometime in the future.

This excerpt is taken from the Global Terrorism Index 2022 produced by Institute for Economics & Peace.

Download the 2022 Global Terrorism Index report.