This framework offers valuable insights for policymakers, international organisations, and researchers working to prevent and mitigate violence worldwide.

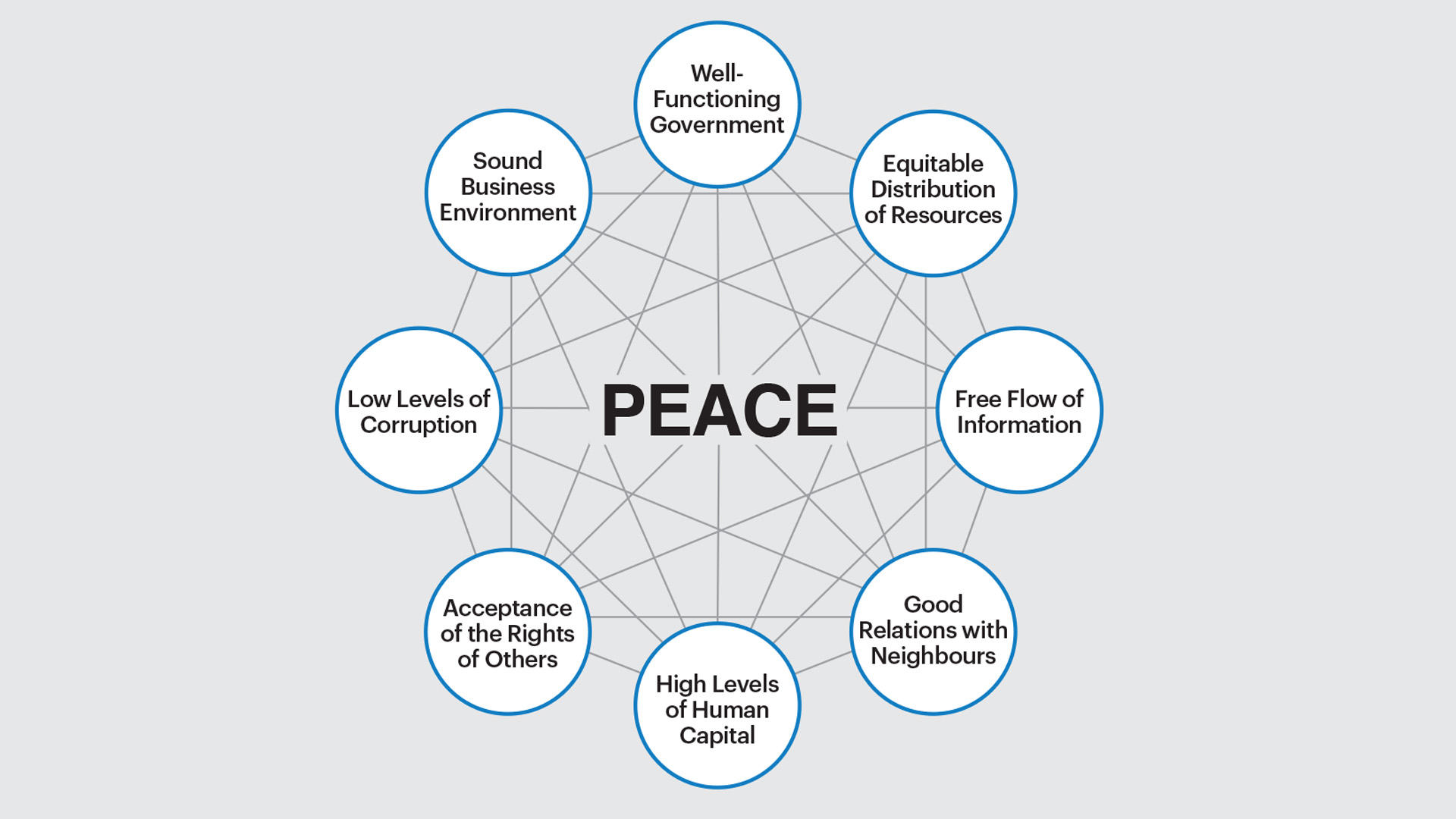

At the heart of this approach lies the concept of Positive Peace, which extends beyond the mere absence of violence. It encompasses the attitudes, institutions, and structures that underpin peaceful societies, including factors such as Well-Functioning Government, Equitable Distribution of Resources, and Free Flow of Information. IEP measures these elements across 163 countries in its Positive Peace Index, providing a comprehensive assessment of societal resilience.

The key aspect of the research is the predictive power of what is termed “Positive Peace deficits.” These occur when a country’s actual peacefulness, as measured by the Global Peace Index, outpaces its level of Positive Peace. In essence, a country may appear peaceful on the surface but lack the underlying structures to sustain that peace in the face of shocks or stresses.

The data supporting this concept is compelling. IEP’s analysis demonstrates that 90% of countries with the largest Positive Peace deficits in 2009 experienced substantial deteriorations in peace over the following years. On average, these nations saw their internal peace scores decline by 11% between 2009 and 2023, compared to a global average deterioration of just 4%.

Libya serves as an example of this phenomenon. In 2009, Libya ranked 58th on the GPI but 115th on the PPI – a significant deficit. In the years that followed, Libya descended into civil war, with its GPI internal peace score plummeting by 46%.

Conversely, countries with a Positive Peace surplus – where societal resilience outpaces current peacefulness – tend to see improvements over time. These nations recorded an average 5.5% improvement in their GPI internal peace scores from 2009 to 2023, countering the global trend of deterioration.

The model’s predictive power is further illustrated by its accurate forecasting of peace deteriorations in Gabon, Burkina Faso, and Niger five years before their recent coups, highlighting its potential as an early warning system.

For policymakers and diplomats, Positive Peace deficits offer a new lens through which to view global hotspots and potential flashpoints. This framework could inform decisions on where to focus preventive diplomacy efforts, how to allocate foreign aid, and even guide peacekeeping operations.

International organisations like the United Nations could enhance existing early warning systems, allowing for more proactive interventions. Multilateral development banks might consider Positive Peace indicators when assessing country risk and designing development programmes.

The private sector, too, stands to benefit from the research. For multinational corporations and investors, understanding Positive Peace deficits could provide valuable insights for risk assessment in emerging markets.

The Positive Peace deficit model represents an improvement in our ability to understand and potentially predict global conflicts. It aligns with and enhances several existing theories in international relations, from Democratic Peace Theory to Constructivism and Liberal Institutionalism.

As geopolitical tensions rise and traditional conflict prediction methods struggle to keep pace, tools like the Positive Peace deficit model become increasingly relevant. By providing a data-driven framework for assessing societal resilience, it can offer a new pathway for evidence-based policymaking in conflict prevention.

In a period of time where localised conflicts can quickly escalate to regional or even global crises, enhancing our ability to predict and prevent violence is not just desirable—it’s essential. The Positive Peace deficit model offers a promising new approach to this critical task, providing a fresh perspective on the persistent challenge of maintaining international stability and security.

Positive Peace deficits, as conceptualised by the Institute for Economics & Peace, refer to the discrepancy between a country’s actual level of peacefulness and its underlying societal resilience. Specifically, a Positive Peace deficit occurs when a country’s ranking on the Global Peace Index, which measures the absence of violence, is significantly higher than its ranking on the Positive Peace Index, which assesses the attitudes, institutions, and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies. This imbalance suggests that a country may appear more peaceful on the surface than its foundational societal factors would support, potentially indicating a heightened risk of future instability or conflict. The concept serves as a predictive tool, allowing for the identification of countries that may be more vulnerable to peace deterioration despite their current peaceful status, thereby offering a new lens for conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts.