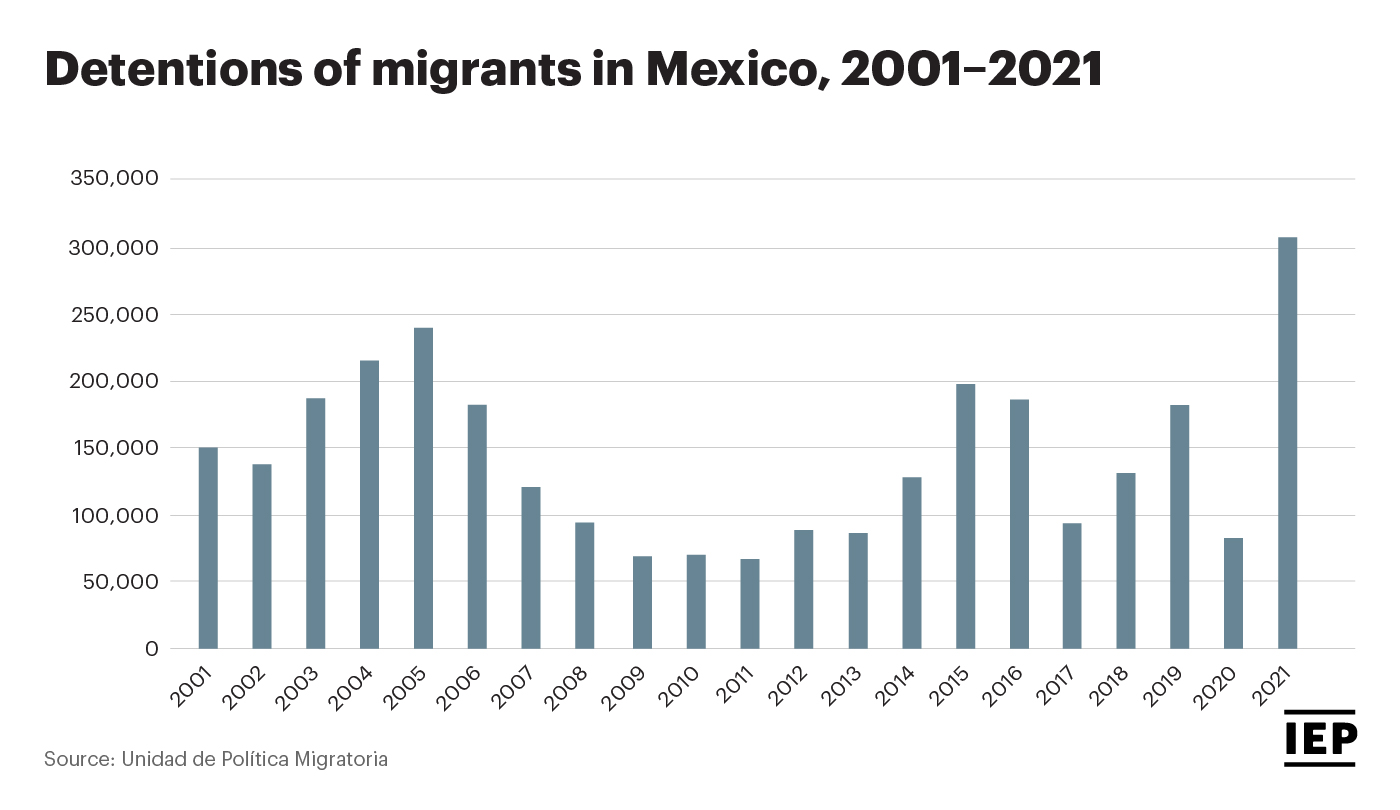

The subject of people fleeing their home countries in search of greater security has become a topic of growing concern in Mexico, as discussed in the Mexico Peace Index 2022. In 2021, there was a substantial increase in number of international migrants and asylum seekers – primarily from Central America – passing through or remaining in Mexico to escape poverty and extreme violence in their home countries. Between January and December, Mexico detained 307,679 unauthorised migrants within its borders, substantially more than the previous record in 2005, when authorities detained 240,269 migrants, as shown in the figure below.

In 2021, migrants from Honduras constituted the largest share of those detained, at 41.3 percent of the total, followed by migrants from Guatemala and El Salvador. Last year also witnessed a rise in migrants from Haiti, who were the fourth largest group, at 6.2 percent of the total. Moreover, the fifth largest group, from Brazil, was reportedly composed mostly of the Brazilian-born children of Haitians.

Chiapas, which shares a long border with Guatemala and is thus the primary gateway to Mexico for Central Americans, was the site of the most detentions in 2021. One-fourth of all detentions in 2021 took place in the state. It was followed by Tabasco, Baja California, Tamaulipas and Veracruz, which each registered between 7.3 and 14.3 percent of all detentions.

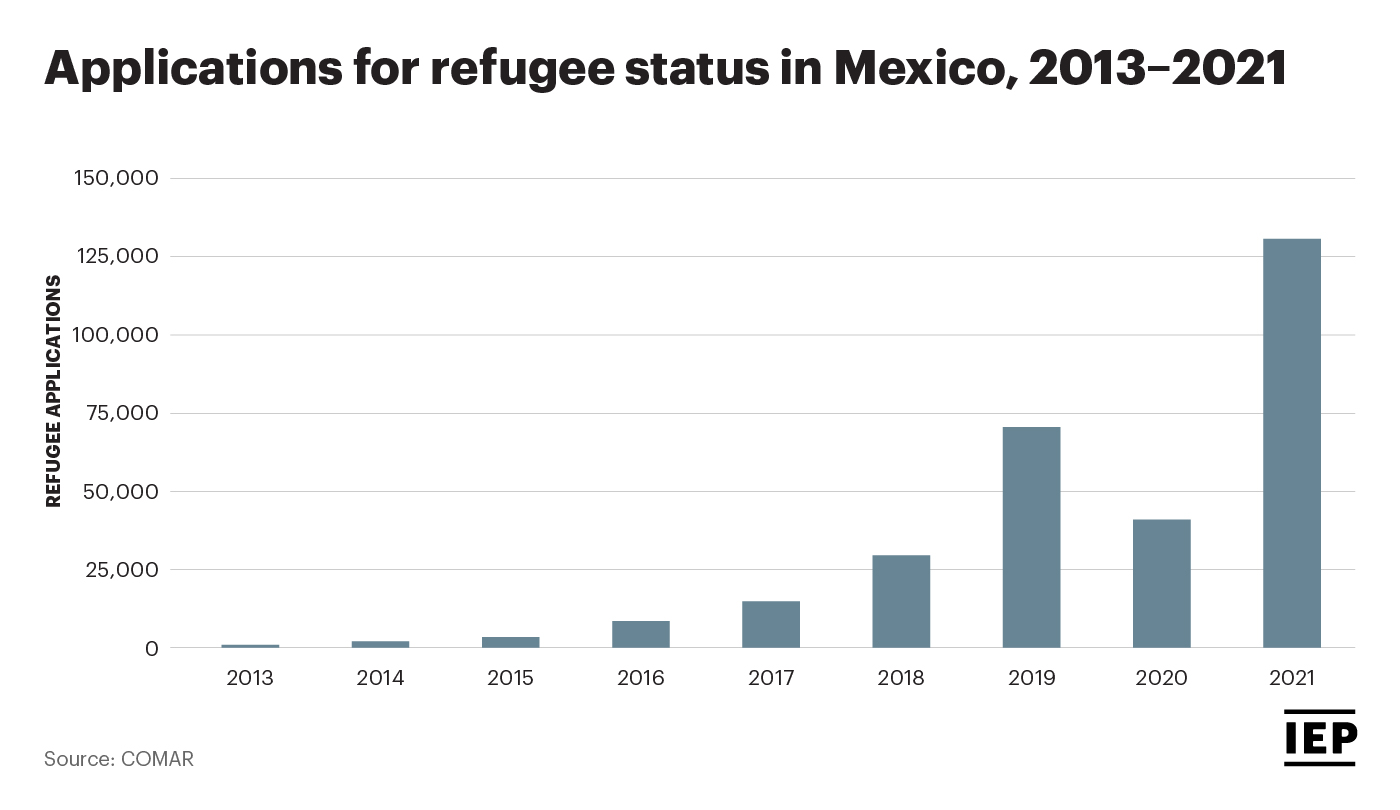

While a majority of migrants enter Mexico with the intention of continuing on to the United States, a major development in 2021 was the significant increase in the number of people seeking asylum in Mexico itself. In part, this has been driven by the heightened difficulty in entering the United States caused by continued enforcement of its so-called “Remain in Mexico” policy. Since 2019, this policy has required migrants presenting asylum claims at the US-Mexico border to stay in Mexico while their cases are processed.

In 2021, the number of migrants requesting asylum in Mexico reached a record 130,863, which was more than three times as many as were received in 2020 and more than 14 times as many as were received in 2016, as shown in the following figure. Haitians and their foreign-born children, who were both blocked from entering the United States and deported from the country by the tens of thousands, represented 45 percent of asylum requests to Mexico in 2021.

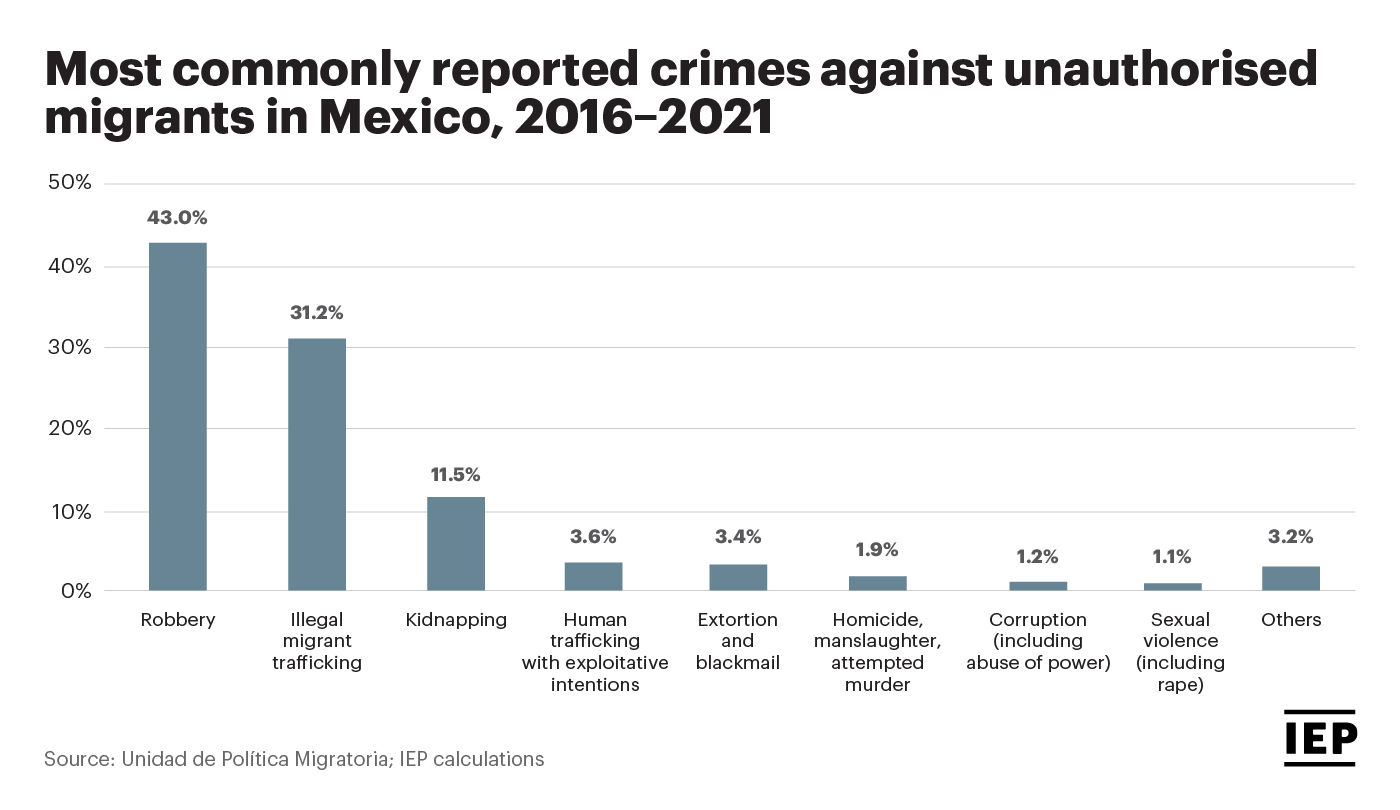

As a result of their irregular status, unauthorised migrants are especially vulnerable to being the victims of crime in Mexico. While underreporting rates among migrants are so high that they are difficult to even estimate, in 2021 there were 701 reports of crimes against unauthorised migrants in the country. This is more than in 2020 or 2019, but significantly fewer than the 1,432 crimes reported in 2018.

Over the past six years, the most commonly reported crime against unauthorised migrants has been robbery, at 43 percent of the total. This is followed by crimes related to the illegal trafficking of migrants, at 31.2 per cent, and kidnapping, at 11.5 per cent, as shown in the figure below. Since 2016, the state registering the highest number of reported crimes has been Chiapas, with 38.3 per cent of the total. However, looking at 2021 alone, Hidalgo had the highest number, with 42.8 percent of the total. In the past six years, migrants from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador have been victimised far more than any other nationality.

While Mexico has experienced a notable decline in total kidnappings over the past several years, there has been a rise in such offenses against migrants. Between 2011 and 2020, a total of 1,518 operations to rescue migrants from traffickers were carried out by the Federal Police and the National Guard through which 48,234 people were rescued. However, the majority of these rescues took place in just two years: 2019 and 2020. While in 2011 there were 51 operations leading to the rescue of 1,100 migrants, in 2020 there were 317 operations leading to the rescue of 15,237.

In addition to the extremely low rates at which migrants report crimes, it is challenging to calculate the incidence of kidnapping and human trafficking offenses against migrants because of the general illegality surrounding the movements of unauthorised migrants. Specifically, it can be difficult to distinguish between situations in which migrants have volunteered to be smuggled and those in which they are held or trafficked against their will, as migrants sometimes place themselves at the mercy of smugglers who may exploit their vulnerable situation in various ways.

However, migrants have increasingly become victims of clear-cut kidnappings involving demands for ransom payments from family members abroad. It has recently been estimated that one out of every ten victims of kidnapping in Mexico is a migrant. The ransom payments have been found to range from US$1,500 to US$10,000, with kidnappers usually demanding more if the victim has family in the United States. One estimate placed crime groups’ earnings from migrant kidnappings at US$800 million over the past decade.

The continued implementation of the United States’ “Remain in Mexico” policy and a number of related developments have placed new pressures on Mexican authorities, particularly at the country’s northern and southern borders. And these pressures have been exacerbated by the record-setting numbers of Central Americans – and people from other parts of the world – entering Mexico in search of safety and opportunity outside their home countries.

While Mexico has long been a major transit country for international migrants, the conditions faced by migrants have historically not represented a policy priority for the Mexican government, as it has understandably given focus to addressing the sizable social challenges – from insecurity to income inequality – that primarily afflict its own citizenry. However, the combination of the unprecedented numbers of migrants that now move through Mexico and its growing status as a destination for asylum seekers point to the need for renewed attention to the protection of non-Mexicans within the country’s borders.

Strategies to identify and punish criminal acts against migrants will be crucial in this regard. However, such measures should not be pursued in isolation, as the most they could achieve on their own would be gains in negative peace – that is, the absence of external manifestations of violence. To be sustainable, measures to protect migrants should also include reforms related to Positive Peace, which consists of the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peace in the long term.

As simply prohibiting the entry of unauthorised migrants would likely not be either practicable or ethically tenable, such reforms might include enhancing institutional capacities to track migrant entries and ensure safer and more orderly movements within the country. They might also entail steps to significantly expand services and housing for migrants, particularly along the US border, where in recent years dangerous and unsanitary encampments have sprung up with tens of thousands of people awaiting notification on their asylum claims to the US.

With regard to attitudes, Mexico is a country that generally values immigrants, and its citizens have demonstrated remarkable acts of generosity to Central Americans making the arduous journey across the country. However, in recent years, there have been slight upticks in anti-immigrant sentiment, and most of the population has been in favour of the stricter measures the government has put in place to stem the unprecedented migrant flows. Bringing greater levels of orderliness to migrant movements could both increase those migrants’ safety and help relieve tensions that have strained the country’s natural disposition of friendliness to foreigners.