This analysis of Mexico’s organised crime landscape is based on the Mexico Peace Index 2023; to explore recent developments, read The organised crime landscape in Mexico in 2024.

Over the past two decades, the dynamics of organized crime in Mexico have undergone substantial changes. Many of these shifts can be traced to the launch of the country’s war on drugs in 2006 and the subsequent disruption of the structures of several well-established criminal organizations. However, changes have accelerated in the past eight years, in part driven by responses to transformations in the drug market in the United States.

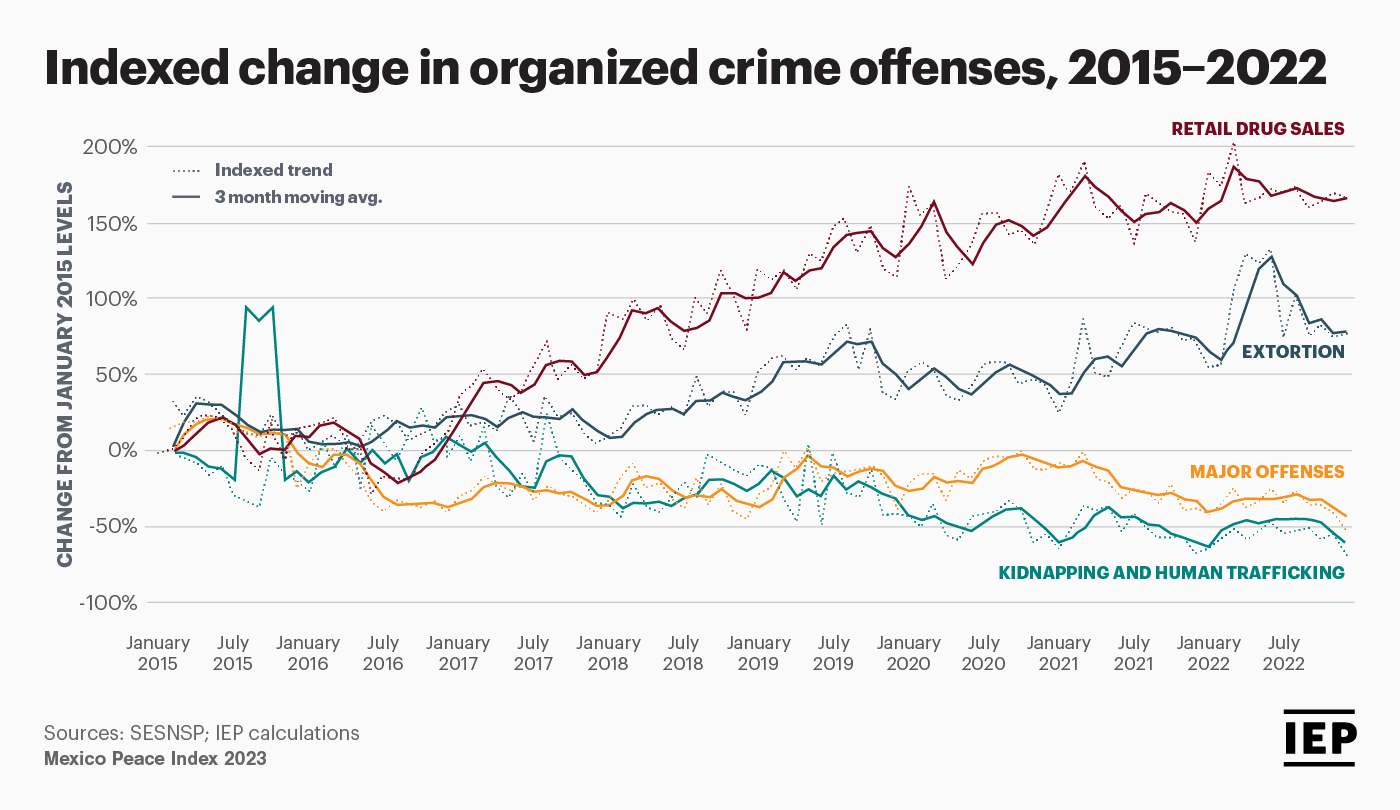

In the newly released Mexico Peace Index (MPI), we track levels of organized crime in Mexico on the basis of four sub-indicators: extortion, kidnapping and human trafficking, retail drug crimes, and major organized crime offenses. Major offenses include federal drug trafficking crimes and criminal offenses committed by three or more people. The figure below shows the monthly indexed trends in the rates of each of these sub-indicators from their levels in January 2015.

The 2023 MPI finds that the national organized crime rate has risen by 64.2 percent in the past eight years. With the exception of a minor decline in 2020, the rate has risen each year since 2016. This rise was driven by deteriorations in extortion and retail drug crimes, with rate increases of 59.5 and 148.7 percent, respectively. In contrast, the kidnapping and human trafficking rate has fallen by 55.4 percent since 2015, while the major offenses rate has fallen by 40.7 percent.

The increases in levels of organized crime in Mexico have been visible not only in these four revenue-generating activities, but also in the country’s heightened rates of homicide and extreme violence. In part as a result of the government’s “kingpin” strategy, which sought to stifle the operations of organized criminal groups by targeting and arresting their leaders, the past decade has seen the fragmentation of a handful of formerly dominant groups. However, this has led to the intensification of competition and more turf wars as smaller and more violent groups proliferated.

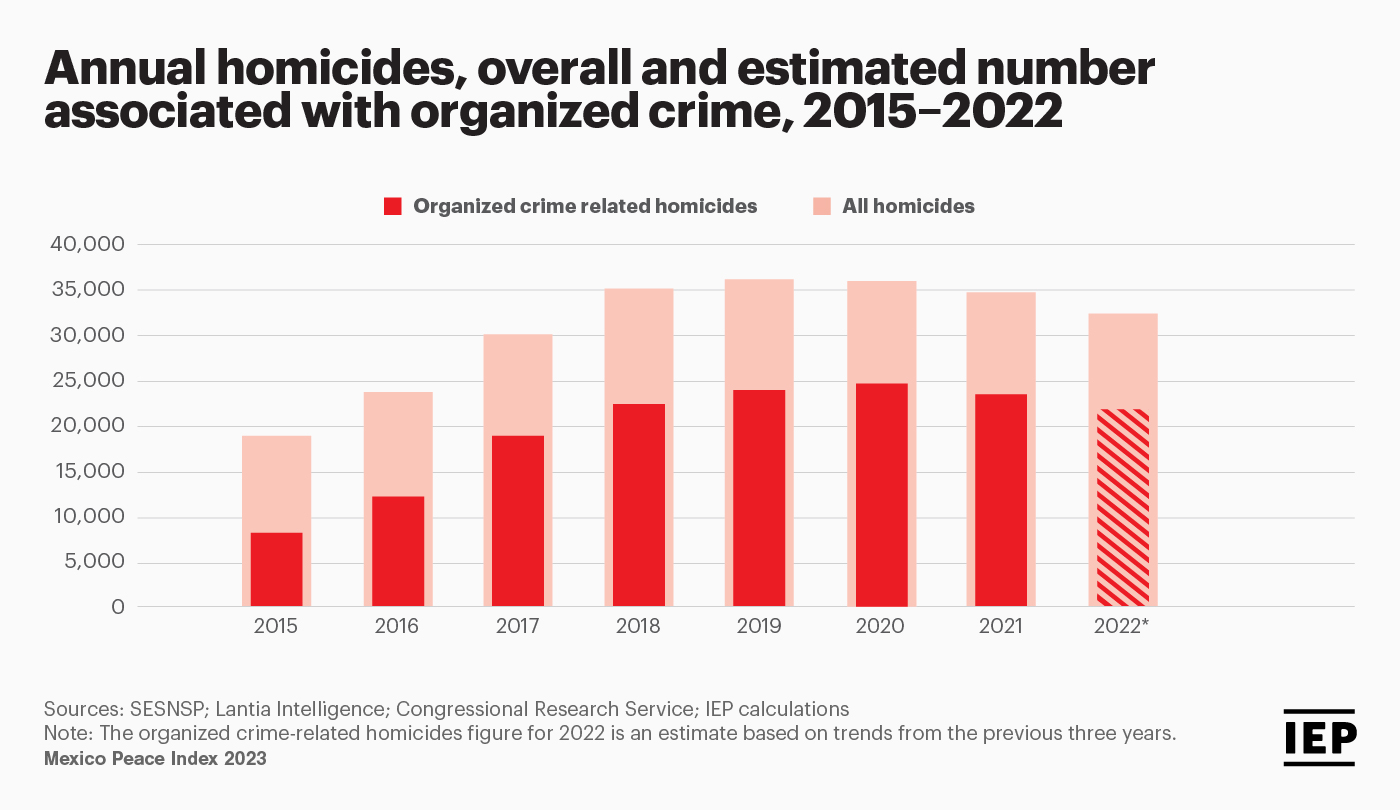

New contests between criminal organizations for control of territory and drug trafficking routes have driven major increases in the number of homicides in Mexico. As shown in the figure below, between 2015 and 2021 the number of homicides linked to organized crime grew from about 8,000 to over 23,500, while the number of homicides not connected to organized crime has remained relatively stable, at around 10,000 to 12,500 per year. According to this measure, organized crime-related homicides rose by 190 percent over the period, while all other homicides increased by just 6.4 percent.

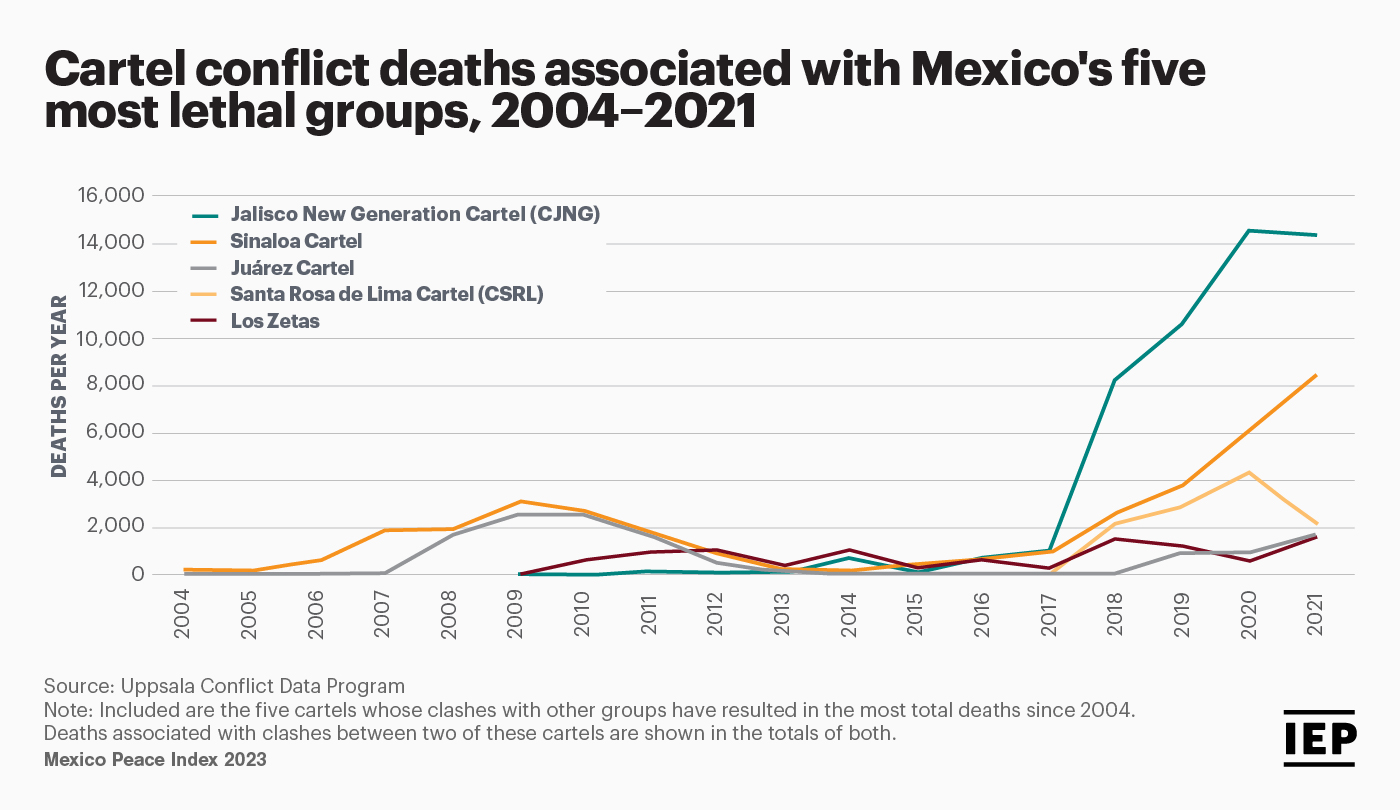

Data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program sheds further light on these dynamics. According to its records, the total number of deaths in Mexico from non-state violence increased from 2,657 in 2011 to 18,783 deaths in 2021. This increase is largely the result of the aggressive territorial expansion of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), which since breaking with the Sinaloa Cartel in 2017 has expanded into 28 of Mexico’s 32 states. The CJNG has been associated with 81 percent of all homicides from cartel clashes since 2013.

The rivalry between the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel, Mexico’s two most powerful cartels, is the deadliest in the country. In 2021, their conflict resulted in at least 4,890 deaths, equivalent to 26 percent of all deaths from cartel-related conflict. Since 2017, cartel conflict deaths associated with the two groups – including their clashes with each other and those with other cartels – have increased dramatically, as shown in the figure below. While in 2015 clashes involving at least one of the two accounted for 42 percent of all deaths from cartel conflict, by 2021 they accounted for 95 percent of such deaths.

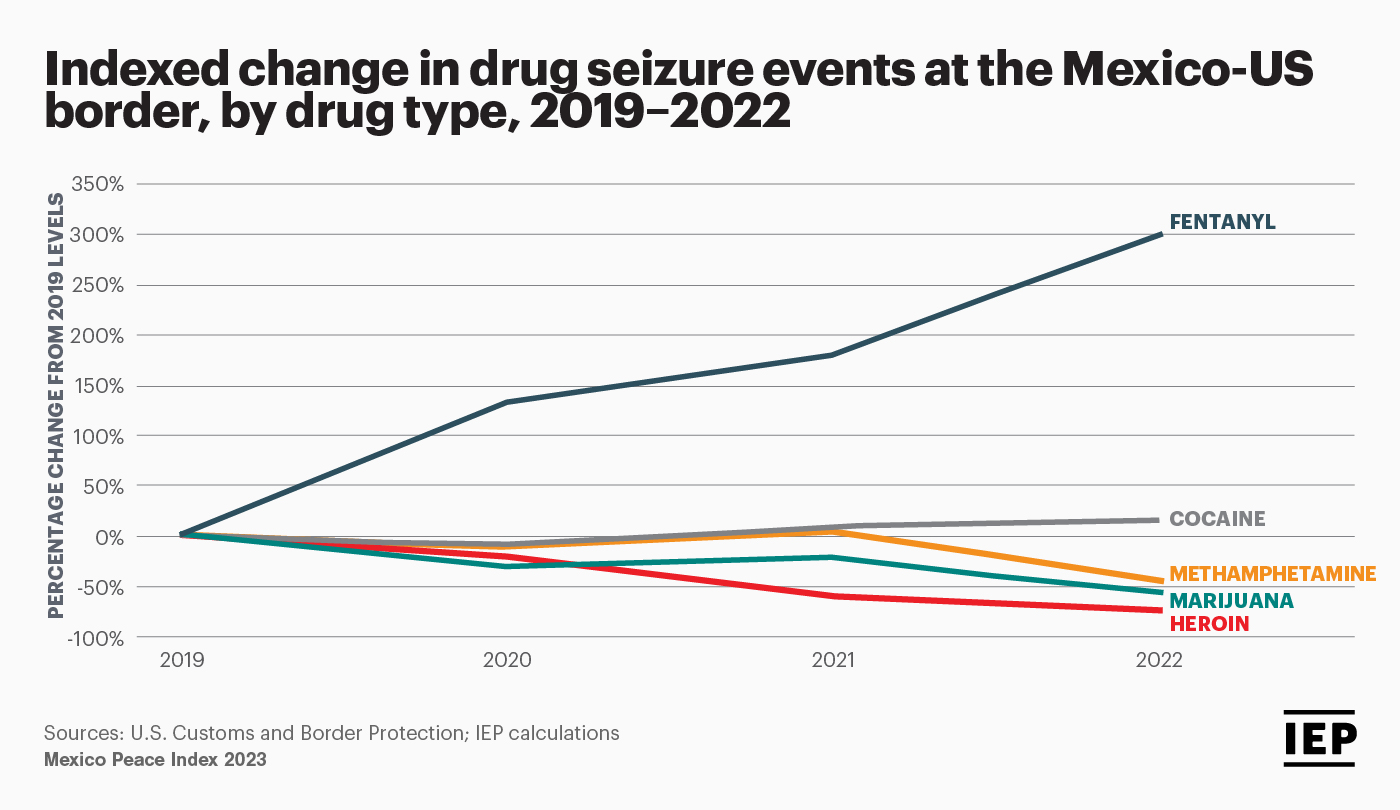

The operations and rivalries of Mexican organized criminal groups have also been transformed by changes in the US drug market. Over the past decade, there has been a growing demand for new synthetic drugs in the United States. In response, Mexican criminal groups have increasingly shifted to the highly lucrative production of fentanyl (as well as methamphetamine), while there have been substantial declines in their production and trafficking non-synthetic drugs like heroin and marijuana.

The decline in the trafficking of marijuana has been particularly noteworthy and has occurred in the context of the widespread decriminalization of the drug in much of the United States. In 2013, when only a few US states had legalized the recreational use of marijuana, the volume of marijuana seizures at all US points of entry totaled just under 1,350 metric tons. By 2022, however, the volume of seizures had declined to 70 metric tons, a 95 percent drop.

As shown in the figure below, the trafficking of fentanyl and methamphetamine has drastically increased in recent years. Between 2016 and 2022, the total volume of fentanyl seized at all US points of entry rose from 270 to 6,668 kilograms, a 25-fold increase. An even more striking trend was observed within Mexico during the same period. From 2016 to 2022, the volume of fentanyl seized by Mexican authorities across all states rose from 11 to 2,114 kilograms, a 192-fold increase.

The shift to fentanyl production has been very lucrative, as fentanyl is highly potent, cheap to produce, and often sold in pill form, meaning that crime groups are able to profit far more, relative to the volume of the drug that is trafficked. The markup of fentanyl prices when it is being sold and distributed can be as much as 2,700 times the price it takes to produce.

Because of its low price, fentanyl is often laced into other drugs such as heroin or cocaine to make them more powerful, addictive, and cheaper to produce. The potency of the drug has led to a spike in overdose deaths in both the United States and Mexico over the past few years. According to data from the US Centers for Disease Control, synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, were involved in over two-thirds of the approximately 108,000 overdose deaths in the United States in 2022.

Against the backdrop of Mexico’s shifting organized criminal landscape, the country will need to give increasing attention to the factors that create the conditions for widespread violence. Since the war on drugs began, the vast majority of institutional responses to criminal violence have focused on the use of public force, particularly the armed forces as the main resource in the fight against organized crime groups. In part as a result of this approach, one of the main objectives of the MPI has been to apply a systemic approach to understanding peace in Mexico, which takes into account factors beyond those directly related to violence containment.

Education, for example, can be a powerful force for curbing violence. A recent study showed that from 1950 to 2005, the increase in the years of schooling from an average of less than one year to more than seven years had a strong effect in reducing homicide rates across Mexico. This finding is consistent in 2022, as states with higher high school enrolment rates tend to have lower homicide rates (r=-0.31). As part of a multisectoral approach that would also include increased investment in Mexico’s under-resourced justice system, greater focus on providing education and opportunity to young Mexicans will be key to undermining the social forces that drive violence.