On the 24th February, 2022, Russia launched its’ invasion of Ukraine. From dramatic effects on food security, to supply chains disruptions, the invasion had seismic impacts across the world. As the conflict rages on, one impact that is becoming increasingly apparent, is the changing role of information technology and the bearing that this has had on the conflict.

The increasing prominence of information and technology in conflict is not a new phenomenon. ISIL were able to recruit nearly 30,000 foreign fighters during the height of their activities, largely through the sophisticated use of social media[1], and when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukraine faced not only a significant military operation, but a substantial cyberwarfare campaign as well.

This cyberwarfare campaign included destructive malware attacks that occurred in December 2015, targeting Ukraine’s industrial control systems networks, leaving around 700,000 homes were without power for several hours. A year later the CrushOverride malware attack blacked out a portion of Kyiv’s total power capacity for over an hour.

Read more on ‘Cyberterrorism, Ukraine conflict and Russian cyberattacks’ in Ukraine Russia Crisis – Terrorism Briefing from the IEP Briefing series.

Alongside the cyberattacks targeting Ukrainian infrastructure, a massive disinformation campaign was undertaken by Russia to shape the narrative. Russia has continued many of these tactics, with Ukraine facing over 685,000 cyberattacks between 2020 and 2021. As a result, Ukraine is now defending itself on two fronts, territorially and in the cyber-sphere.

Russia, already among the world’s top ten most targeted countries with cyberattacks and has experienced a further uptick in attacks in recent months. Cyberattacks in Russia have risen five fold since the invasion began, with hacker groups such as Anonymous declaring war on Russia, making Russia the most attacked country in the world.

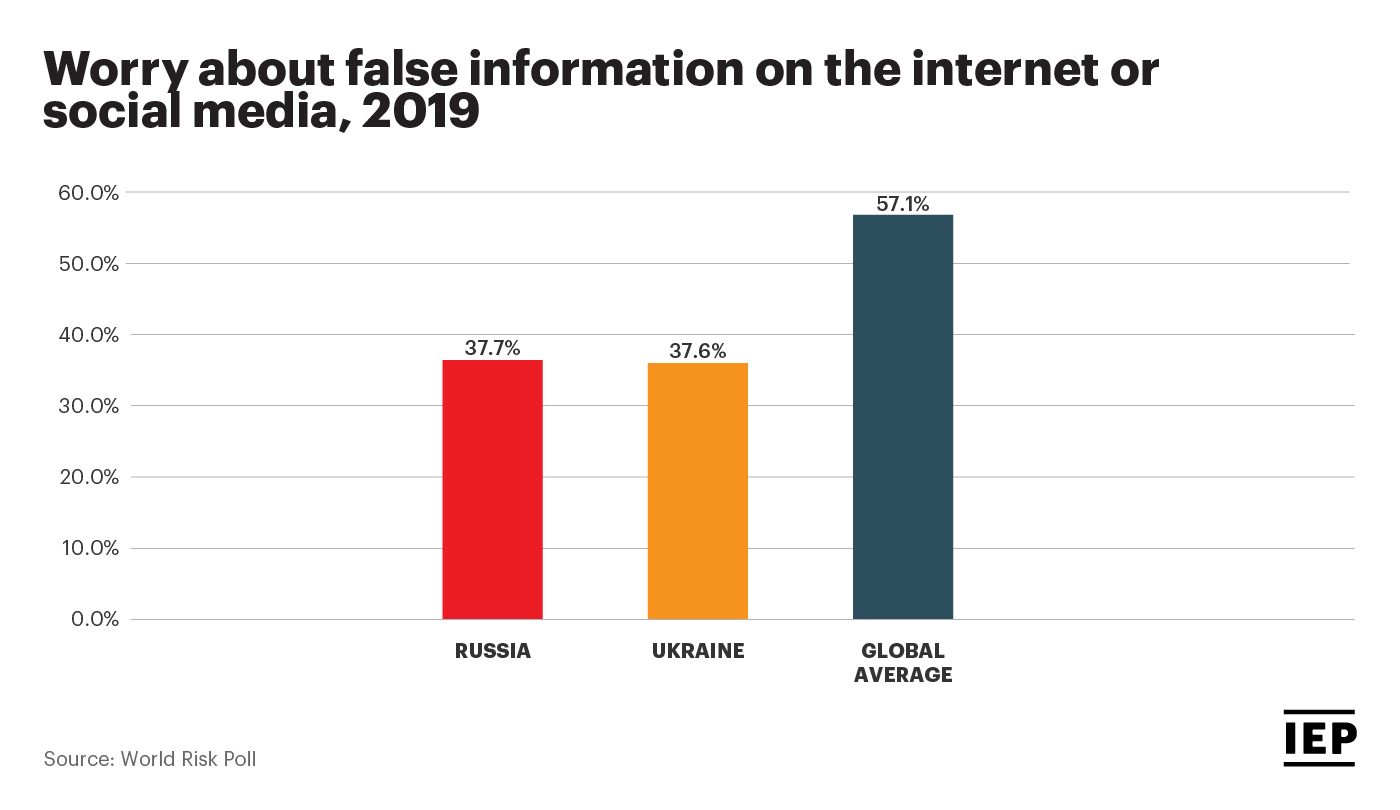

Despite the massive cyber threats in this region, threats that continue to rise, worry over false information on the internet is among is lowest in the world in both Russia and Ukraine. In both countries less than 38% of people were worried about online misinformation, significantly less than the global average of over 57%.

The disparity between actual and perceived threats in this region suggests that internet users are likely to be more susceptible to online misinformation and this explains why it plays such a fundamental role in the cyberwar.

Certainly on the Russian side, a tightly controlled state-run media and the substantial use of disinformation, both from official state sources and online via bots, has helped the state exert narrative control over the conflict. This explains, in part, the low levels of opposition to the invasion within Russia.

Read more on the ‘Perceptions of Risk’ in World Risk Poll: Spotlight on Ukraine and Russia from the IEP Briefing series.

In the early stages of the war, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, from the frontlines of the conflict, engaged, over Zoom, in a whistle-stop tour of Ukraine’s allies to drum up support for Ukraine. The international media was presented with powerful images of Zelenskyy dressed in combat fatigues, begging world leaders to sanction Russia and supply Ukraine with the arms needed to defend themselves. Much of this support and many of these sanctions did indeed arrive and this has had a huge impact on the conflict thus far.

Similarly, Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Federov, another key player in this social media battle, has used twitter pressure private companies, from tech giants such as Apple and Amazon, to thousands of small to medium sized businesses, to limit their business in Russia. Early on in the conflict, Federov tweeted Elon Musk directly, arranging the acquisition of a number of Starlink terminals, providing satellite internet connectivity in Ukraine.

Maintaining internet connectivity in Ukraine has been critical and the weaponisation of social media has not been limited to elite actors. Grassroots movements within Ukraine have seen citizens sharing content from the conflict zone, engaging donors in other countries to raise money for military supplies and garner assistance for those displaced by the conflict. This savvy use of information and social media has seen Ukraine make significant early gains in the information war and certainly helped shape the international response to the crisis.

The Russian response has been markedly different. The Putin regime is well practiced in propaganda campaigns and where Ukrainian social media movements have been largely bottom-up, Russia’s top down authoritarian approach has been typified by limiting the free flow of information, suspending access to social media and engaging an army of paid trolls to work round the clock to parrot the Kremlin line and discredit reports emerging from Ukraine.

Russia also mobilised the zampolits, a military institution made up of military priests, psychologists and military commanders charged with ensuring Russian citizens and service personnel remain loyal and motivated to the Russian cause. Russia has complimented these actions with strict censorship laws with lengthy prison sentences for those who openly undermine the invasion of Ukraine, or refer to it in any way other than the official Kremlin line of ‘a special military operation’.

While a hotly contested propaganda war is not a new concept, the Ukraine conflict has represented a marked shift in the manner in which information is gathered and disseminated in a highly fluid combat environment. The instantaneous nature of social media has added a new component to the conflict.

In the build-up to the invasion, Russian troop movements along the borders were heavily documented on social media platforms such as TikTok and Telegram. Since the invasion began in earnest, Ukrainian social media users have been, in real time, documenting Russian activities in Ukraine. This information has had an enormous strategic benefit for Ukraine and has allowed the military to use Meta to crowd source data on Russian troop movements.

Meta and other platforms have been used by Ukrainian armed forces to collate information about Russian operations and guide armed drones and new generation light anti-tank weapons (NLAW) in Ukraine’s defence. This sort of information gathering is a game-changer. Activities, historically carried out by the military or intelligence agencies, can be carried out by anyone with a smartphone and internet access.

While a rapid flow of information certainly has its benefits, there are a number of challenges posed by the increasing prominence of information warfare in conflict. The most significant difficulty is dealing with the overwhelming amount of information available. Content is largely disseminated on these platforms with little to no analysis and it becomes increasingly difficult, if not impossible to sift through it fast enough. Separating what is genuine and what is misinformation is a difficult task and the speed at which information travels on social media makes this even more challenging.

Social media companies themselves have struggled to keep up with this shifting landscape, with Meta having amended its content policy on at least 6 occasions since the conflict began. These amendments at various times have dictated what sort of content is allowed on these platforms and have resulted in confusion from users and moderators as private companies attempt to navigate these complex geopolitical events while prioritising their own vested interests.

Many of these technologies are in their nascent stages and there is great uncertainty about the long-term implications for future conflicts. The use of social media as an intelligence gathering tool has the potential to be deeply problematic. While crowd sourced social media information has been used by Ukraine in its defence against Russia, there have been a number of incidents of nefarious actors and authoritarian states using the information available to target opponents and silence dissent. Furthermore, these technologies provide a platform for authorities to control and manipulate the spread of information. The global reach of social media has allowed misinformation to rapidly spread, one notable example early on in the Ukraine conflict was the widely shared deepfake video of Zelenskyy telling Ukrainians to surrender.

It is clear that these emerging technologies represent a grey area. While the rapid flow of information offers enormous potential for individuals to remain informed and connected, the challenges these burgeoning technologies pose should not be overlooked.

[1] Zeitzoff, T. (2017). How Social Media Is Changing Conflict. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(9)