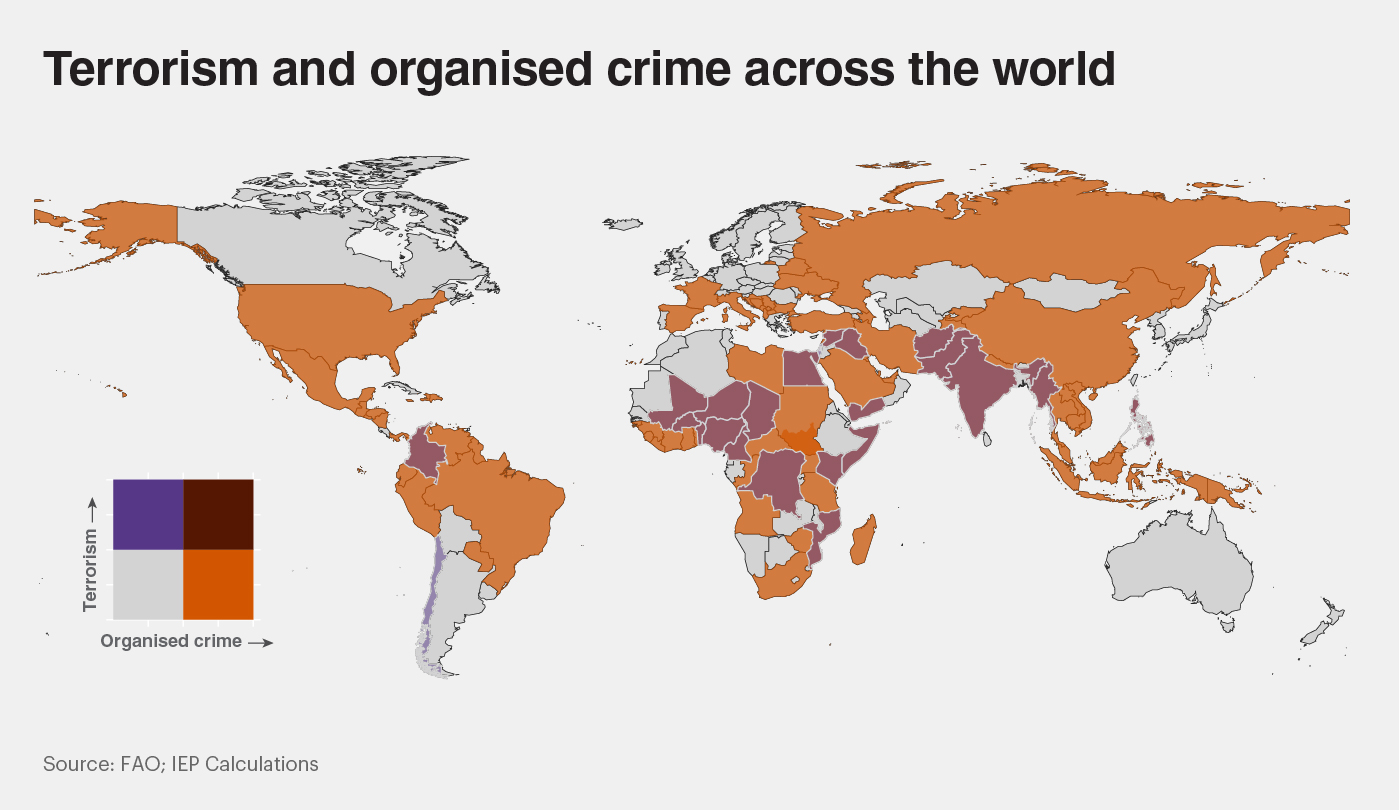

The relationship between organised crime and terrorist groups clearly interlinks, particularly in the Sahel region of Sub-Saharan Africa. Transnational and domestic organised crimes can allow terrorism financing with subsequent illicit economies working to grow violent extremism. These correlated interactions occur at three levels as they either coexist, cooperate or converge into one group. This connection is often referred to as the ‘crime-terror-‘nexus and understands how illicit economies prosper when created or allied with terrorist groups.

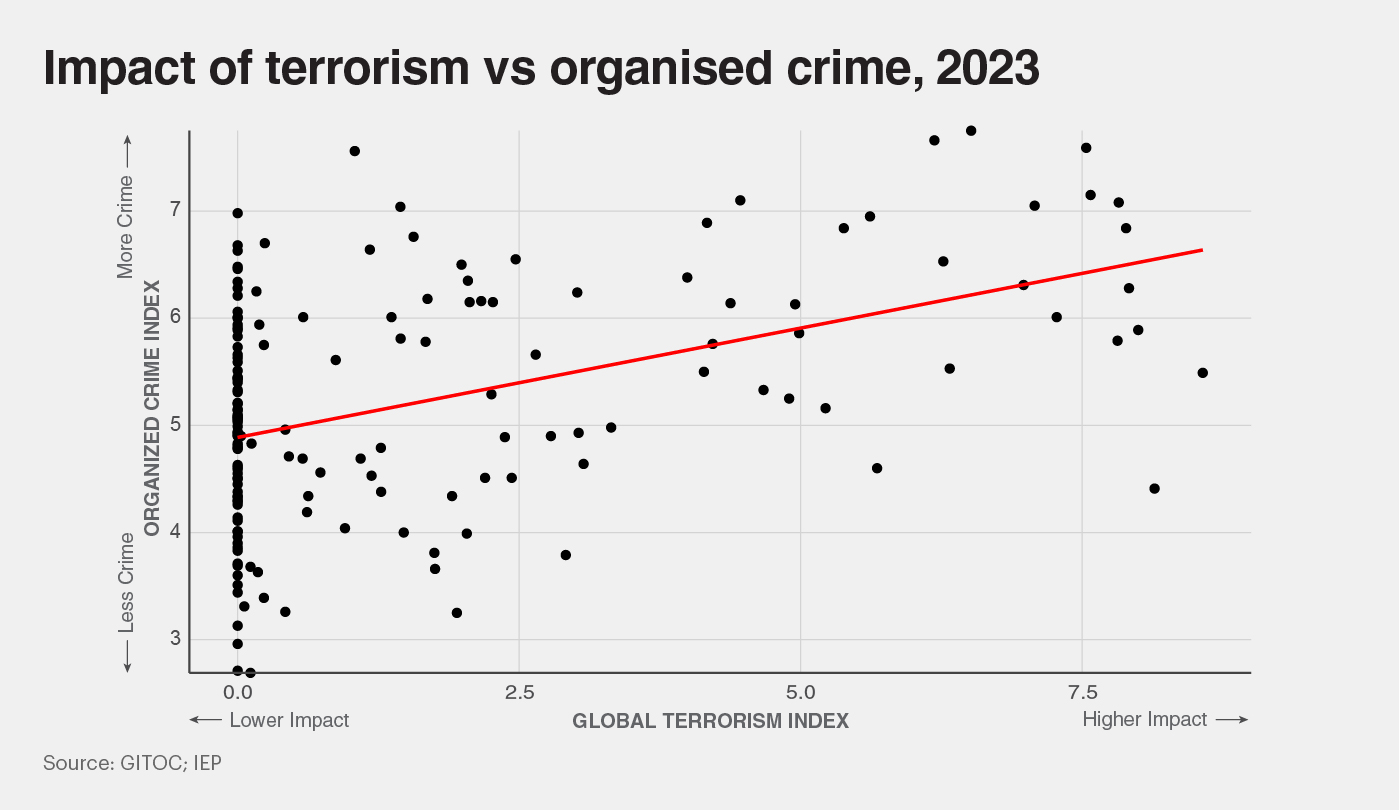

Many of these groups co-opt illicit economies which tax unregulated legal enterprises and ensure security and protection for the transporting of prohibited and counterfeit goods, arms and drugs. It extends into kidnappings and ransoms alongside other illegal activities such as livestock rustling and artisanal gold mining. While regions may experience high levels of organised crime, they may not experience a higher impact of terrorism; however, in countries with a high terrorism impact, there is almost always a coinciding large organised crime presence.

The crime-terror nexus recognises the three relationships between organised crimes and terrorist groups. Coexistence refers to both groups working operationally in the same geographic area; whilst there may be some overarching benefits, there is not a direct working link between the two. Cooperation instils some level of working together for them both to benefit economically and socially but they still remain two distinct bodies. Lastly, convergence understands the groups taking over elements of the others operations.

For example, Islamic State generated $2.9 billion through illegal activities such as ransom, forced taxation and oil smuggling that was able to fund their terrorist activities. Additionally, the Taliban funded a large portion of their operation through smuggling opium poppies for heroin production.

There are various reasons for the linkages between terrorists and organised crime. This varies from antagonistic viewpoints towards authorities to personal connection created in prisons or shared networks. A primary reason for terrorist groups to partner is because of a reduction in state sponsorship following the Cold War and War on Terror, when increased attention and sanctions put these relationships at risk.

Another fundamental enabler of the relationship comes from alliances founded on shared operational territory – strong with terrorist groups that control territory. Increasing involvement with organised crime four times due to weak state capabilities. The groups are able to work as ‘regulators’ and enable illicit economies in these regions, distributing the benefits to the population – meaning increased popular support for mobilisation and recruitment. As often, terrorist groups do not earn profits by engaging in these activities themselves, but rather, through imposing taxes, levies, or providing security for the individuals or groups performing the illegal crime.

As aforementioned, Sahel particularly Central Sahel encompassing Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, sees the strongest links and correspondingly the biggest deterioration in Positive Peace. Some of the most prominent terrorist groups in the region are Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’adati wal-Jihad (JAS or Boko Haram), ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province), JNIM (Jama’at Nustratal-Islam wal- Muslimeen).

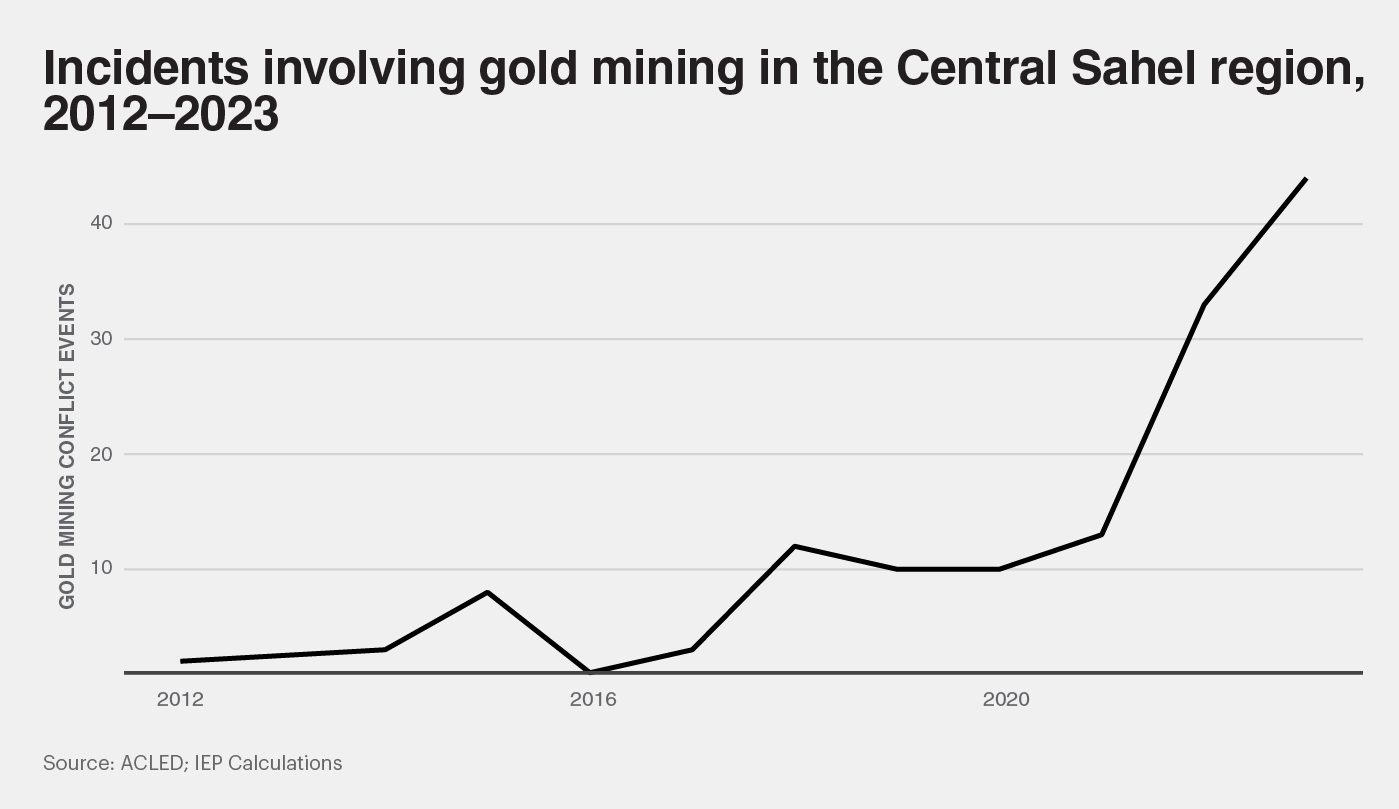

The region is affiliated to be the ‘hotbed of terrorism and violent extremism (TVE) in Africa’. Many of these states have little government control of areas, with Burkina Faso’ government estimated to only control around 60% of territory. Therefore, terrorist groups can compete and succeed in gaining influence and power in those areas where the state carries little control. This competition coincides with attempted territorial expansion. For example, in Burkina Faso and Mali, key terrorist group JNIM coins into the fruitful gold mining industry as a way to extend influence into these regions.

In this, they don’t predominantly trade or smuggle the minerals themselves but rather control the territory and provided security to local miners. The group charges less than the pro-government militia and can strengthen relationships and partnerships with civilians, proving their possibility as an alternate governing force. Highlighted by the over 2000 miners that are estimated to be working in JNIM controlled N’Abaw goldfields in Mali. Furthermore, these minerals can be used to trade with Private Military Companies (PMCs) and Mercenaries for firearms, ammunition and military grade equipment to traffic and utilise in their own perpetuation of violence and control.

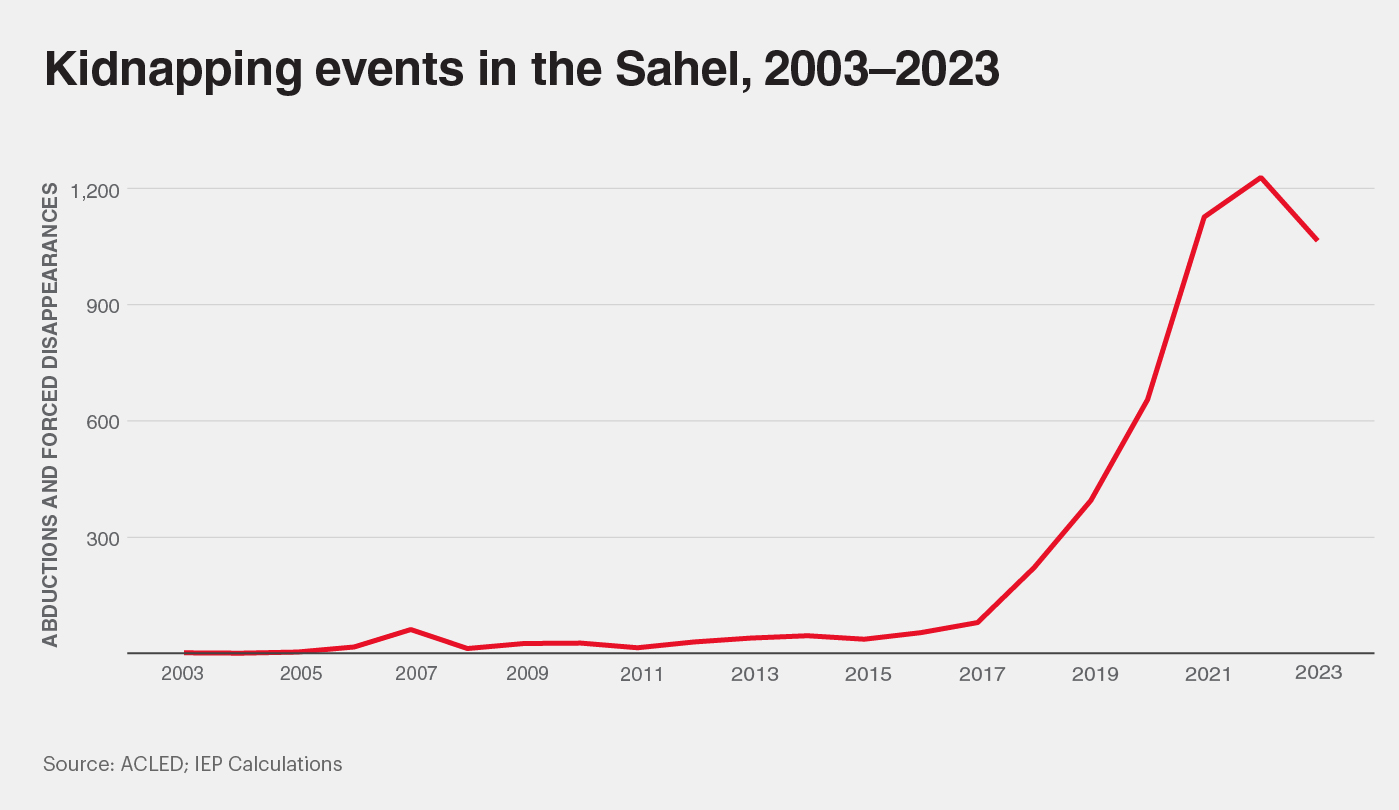

Additionally, actions like kidnaping and ransom are prominent, estimated to account for 40% of JNIM’s revenue in 2017. Alongside the economic benefits with ransoms, kidnapping can aid the groups with prominent individuals being taken for political purpose in order to gain strategic advantages or crucial intelligence.

Organised crime in the Sahel has also become transnational in nature, as Transnational Environmental Crimes, or TECs, becomes a major income generating channel for terrorist organisations in the region. TEC overtook drug trade as the major income channel. Including Illegal logging and trade of wildlife of great apes, ivory, horns, timber.

The transnational nature of illicit economies and terrorism financing in the Sahel has shown the need for a multidimensional response based on increased cooperation among Sahelian countries with the support of their regional and international partners.

There have been several summits and resolutions by the African Union (AU) assembly, Member States and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) attempting to create and strengthen comprehensive frameworks around the relationship of organised crime and terrorists. The 16th assembly of the AU in 2022 focused on legislation surrounding terrorism financing, particularly ransom payments. Additionally, the UNSC resolution 2482 encouraged member states to make use of INTERPOL analytical databases in order to counter links between terrorism and organised crime – domestic and transnational. However, in December 2023 the council expressed further concerns in the introduced Resolution 2719 over the growing threats of the relationships and suggested further action be taken.

A multi-dimensional and coordinated response is required at the domestic and international level which would pinpoint vulnerable sectors exploited by terrorist. Such as in the Sahel region, where governments are urged to conduct NPO risk assessments to identify organisations most at risk of becoming a channel for terrorism financing. Furthermore, the utilisation and establishment of databases to analyse biometrics and data can support states in fighting corruption. These intelligence sharing mechanisms should also be united across regions. Scholars and the council agree that only with synergy in legislation and frameworks, can the alliances be disrupted.

The complicated and encompassing relationship between organised crimes and terrorist groups is overt. Through the creation of illicit economies in taxing upregulating legal enterprises and ‘regulating’ gold mines, ensuring security for criminal groups in trafficking and smuggling prohibited goods, ransom and kidnapping there is a level of control garnered by these groups.

Particularly in areas of little state governance, they can garner public support by delivering benefits from illicit economies which can then mobilise violent extremism. Recognised to be a substantial issue within particularly the central Sahel region, the UN urges urgent action by member states and suggests synergy and comprehension in any possible legal or operational frameworks used to alleviate the issue.

Ongoing action and changes reflect the complexities of the relationship between organised crime and terrorism, as can be read further in the Global Terrorism Index 2024 report.