One frontier of this competition lies in an unlikely place: the deep sea. Nations and corporations are now exploring the ocean floor for mineral deposits, a development that promises both opportunities and challenges for sustainable development. This pursuit of undersea resources raises important questions about environmental preservation, international cooperation, and the true cost of our green energy ambitions.

The Ecological Threat Report indicates the escalating competition for resources between nations is a primary driver of conflict. As nations transition to renewable energy sources, the demand for critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel is expected to skyrocket.

The report projects an increase as high as 500% in demand for these materials by 2050, driven by the production of clean energy technologies like electric vehicles, wind turbines, and solar panels. The recent conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo highlights issues related to resource scarcity and competition. The M23 rebel group, supported by Rwanda, controls many mining activities, including one of the world’s largest coltan mines, a crucial resource for modern electronics. As a result, the DRC is ranked 158th on the Global Peace Index, and is experiencing high levels of violence, unrest and instability due to its natural resources.

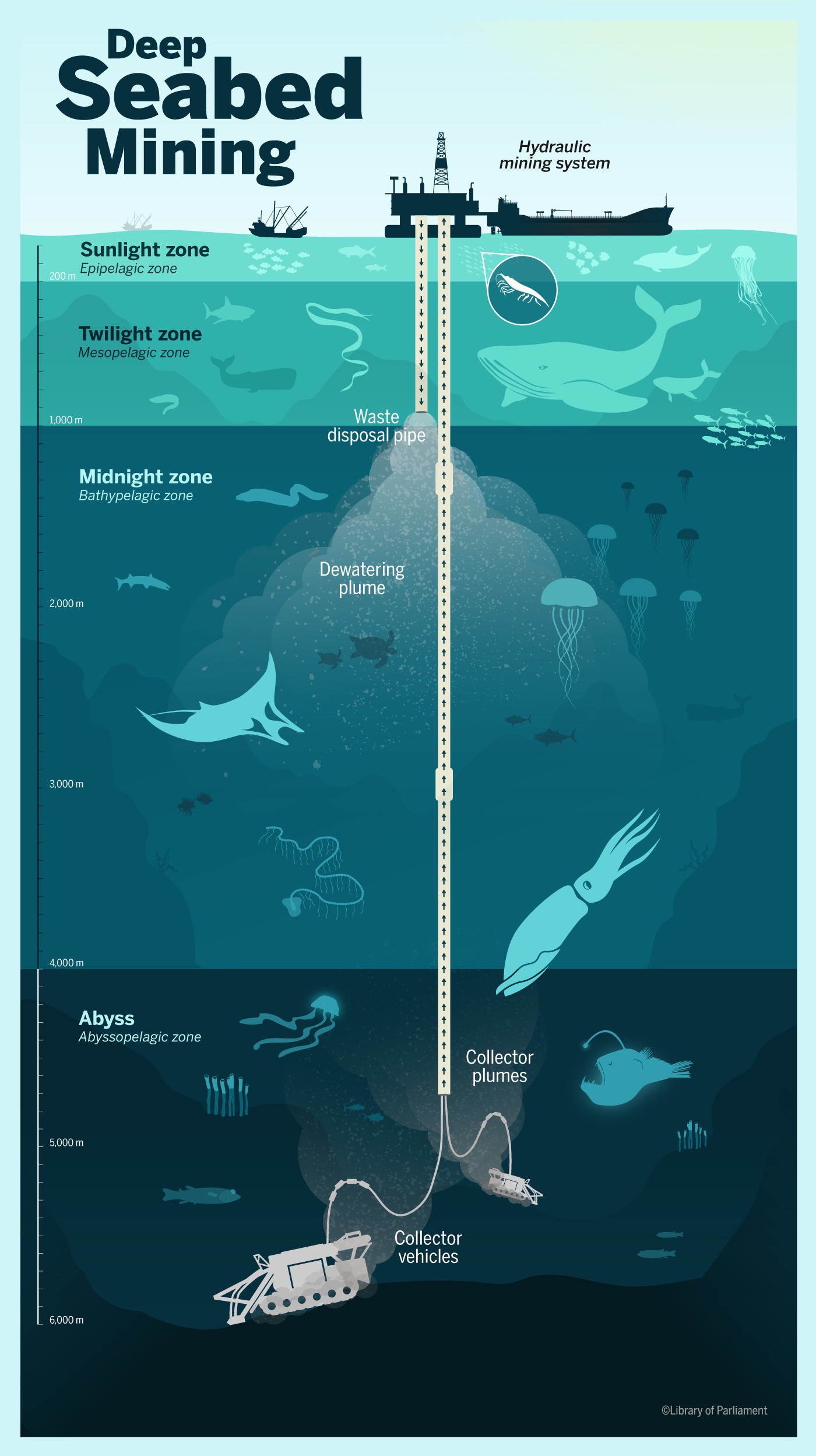

Deep Sea Mining (DSM) involves retrieving mineral deposits from nodules on the ocean floor, typically at depths exceeding 180 meters. These valuable nodules contain cobalt, copper, nickel, and other minerals crucial for producing green technologies. The most economically viable deposits are found in the north-central Pacific Ocean, the southeastern Pacific Ocean, and the northern Indian Ocean.

A global interest lies in the Clarion-Clipperton region, a vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico that has been identified as teeming with lucrative nickel, cobalt, and rate earth minerals on the ocean floor.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) mandates that states govern deep-sea mining within their national jurisdiction. For areas beyond national jurisdiction, such as the Clarion-Clipperton Region, which comprises about 60% of the ocean floor, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulates deep sea mining activities. However, the ISA’s Mining Code remains incomplete, with only finalising exploration regulations and exploitation laws under review. ISA meetings have exposed deep divisions in the Pacific over deep-sea mining. More than 30 countries, including Vanuatu, Palau, and Tuvalu in the Pacific, support a precautionary pause on deep-sea mining. Others including Kiribati, Nauru, Tonga and the Cook Islands have all expressed interest in deep-sea mining exploration.

Proponents of DSM argue that it could help meet the world’s growing demand for critical minerals essential for green technologies. Some view it as a potentially less harmful alternative to terrestrial mining, as it doesn’t generate the same harmful waste by-products or cause deforestation. Additionally, DSM offers the least amount of human life interference and the least human cost.

Despite its potential benefits, DSM faces significant challenges and opposition. The environmental impact of DSM on marine ecosystems remains largely unknown and potentially devastating. Scientists warn that DSM could degrade biodiversity, water quality, and fish stocks, as well as disrupt ocean currents. There are concerns about the long-term effects on species and ecosystem disruption, including impacts on feeding and reproduction due to noise and light pollution in naturally dark and silent environments. Disrupting these ecosystems could potentially impair the ocean’s capacity to act as a ‘carbon sink’ for the world to mitigate global temperature rises, exacerbating climate change-related threats. These environmental concerns can exacerbate existing resource driven conflicts.

Of particular concern are the potential impacts on the Pacific Island nations, which are at the forefront of the deep-sea mining debate. The Pacific Island states are heavily dependent on marine resources for their economies and food security, which DSM may heavily impact. Many Pacific Island economies such as Kiribati, Vanuatu and the Marshall Islands heavily rely on sectors such as fishing, tourism, and renewable energy, collectively known as the Blue Economy. The potential impacts of DSM on marine biodiversity could undermine these crucial sectors.

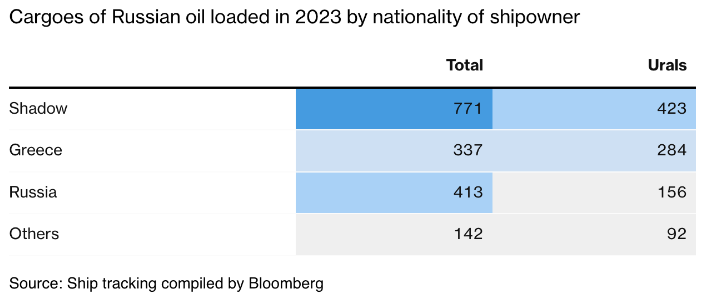

The global competition for resources has given rise to a phenomenon known as dark fleet or shadow fleet. This term refers to a growing number of vessels operating outside established maritime regulations, often used to transport oil from sanctioned producers like Russia and Iran. They do not comply with rules that govern maritime operations, particularly by lacking western insurance protection and turning off automatic identification systems (AIS). These fleets present a grave concern for environmental safety, as they are more prone to incidents and accidents than in regular shipping, as other vessels and authorities don’t know their location. Without proper insurance, potential incidents involving these vessels results in considerable expense for the countries in whose waters the accidents occur.

Since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, the fleet has grown to more than 600 tankers and other types of vessels. Around 400 crude-oil tankers were among the vessels that had gone dark, account to around 20% of the world’s total crude oil fleet.

Due to the sanctions placed by Western nations, Russia has turned to China and India to sell their oil under the covers of the dark fleet, intensifying the race for resources, particularly between China and the US.

The South China Sea has become a focal point in the global race for resources, with its strategic importance and importance for traditional maritime trade routes. In 2016, more than 21% of global trade was estimated by the UN to have travelled through it, and it contains extensive oil and gas reserves. This region has been identified as a potential hotspot for resource driven conflict, particularly to competing claims over fisheries and potential mineral deposits.

It has become a hotspot for geopolitical tension in the area, becoming highly contested. China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan all have claims over areas within the 3.5m sq km area, many of which overlap. Brunei is the only party that does not lay claim over any disputed islands, but it does say part of the sea falls within its exclusive economic zone. The US has also entered the arena, exacerbating US and China tensions by vowing to defend its allies against China in the territorial disputes.

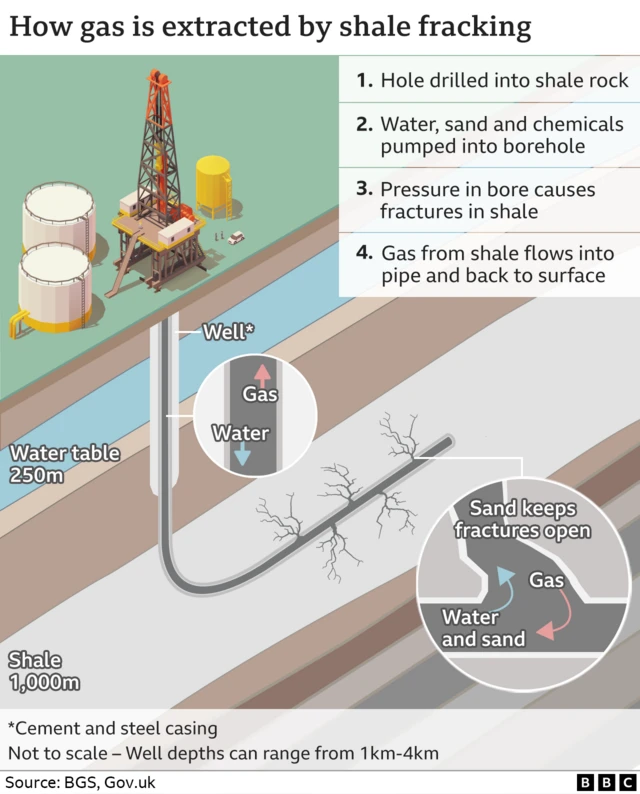

Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’, has significantly impacted global energy markets and resource competition. This technique, which extracts gas and oil from shale rock by injecting high-pressure mixtures of water, sand, and chemicals, had reshaped geopolitical dynamics.

The rise of fracking has altered traditional energy dependencies, enabling countries like the US to reduce reliance on foreign oil sources. However, fracking remains controversial due to its environmental and health impacts. The injection of fluid at high pressures into rock can cause earth tremors, which are small movements in the earth’s surface. This can lead to habitat loss and have human impacts.

Water resource competition and contamination concerns is a global issue affecting geopolitical tensions and are significant issues associated with fracking. The process requires large volumes of water mixed with sand and chemicals, thus contaminating water supplies and aquatic ecosystems. The disposal of wastewater from fracking operations also presents challenges, as it can contain high levels of salts, toxic metals, and radioactive material. Studies suggest that increased rates of adverse health outcomes in communities near fracking sites including the development of asthma and longer-term health impacts.

Proponents of fracking argue that it offers significant economic benefits, including lower energy prices for consumers and reduced dependence on coal.

The pursuit of deep-sea minerals introduces new dynamics to global peace and security. As nations vie for control over these resources, existing tensions may intensify, and new conflicts could emerge. The competition for undersea territories, particularly in areas like the South China Sea, has the potential to exacerbate regional disputes. The development of ‘dark fleets’ – vessels operating outside established maritime regulations – pose challenges to international law and order at sea.

These evolving scenarios underscore the need for robust diplomatic frameworks and conflict resolution mechanisms. The management of deep-sea resources will likely become a critical factor in maintaining global stability, requiring careful balance between national interests and collective security. As the international community grapples with these challenges, the decisions made about deep-sea mining will not only shape environmental and economic outcomes but also influence the landscape of global peace for years to come.