This is the second edition of the 2021 Ecological Threat Report (ETR), which analyses 178 independent states and territories.

Produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the report covers over 2,500 sub- national administrative units or 99.9 per cent of the world’s population.

View this post on Instagram

The 2021 Ecological Threat Report assesses threats relating to food risk, water risk, rapid population growth, temperature anomalies and natural disasters.

These assessments are then combined with national measures of socio- economic resilience to determine which countries have the most severe threats and lowest coping capabilities.

These are the countries most likely to suffer from increased levels of ecological-threat related conflict. The report also looks at the future, with projections out to 2050.

Many ecological threats exist independently of climate change. However, climate change will have an amplifying effect, causing further ecological degradation and pushing some countries through violent tipping points.

Countries with high population growth are amongst the most ecologically degraded. The combination of weak socio-economic resilience, extreme ecological risk and rapid population growth can result in societal collapse.

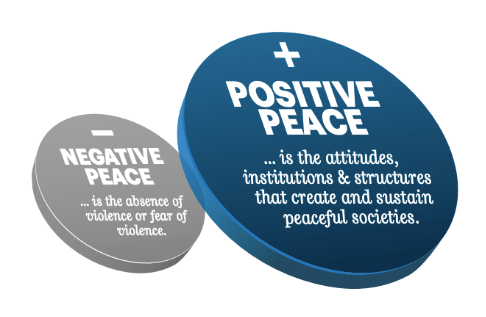

The report uses IEP’s Positive Peace framework to identify countries without enough socio-economic resilience to adapt to or cope with these future shocks.

Positive Peace has a strong statistically significant relationship to peace, and this framework has proven successful in forecasting substantial falls in peace and predicting superior economic growth.

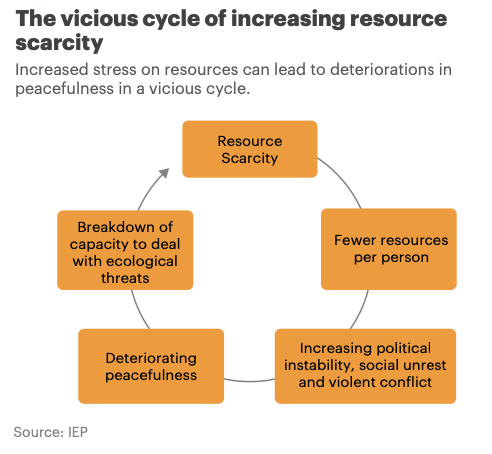

The main finding from the 2021 Ecological Threat Report is that a cyclic relationship exists between ecological degradation and conflict. It is a vicious cycle whereby degradation of resources leads to conflict, and the ensuing conflict leads to further resource degradation.

Breaking the cycle requires improving ecological resource management and socio-economic resilience. The resilience and adaptability of the socio-economic system, referred to as the societal system, will generally determine the outcome.

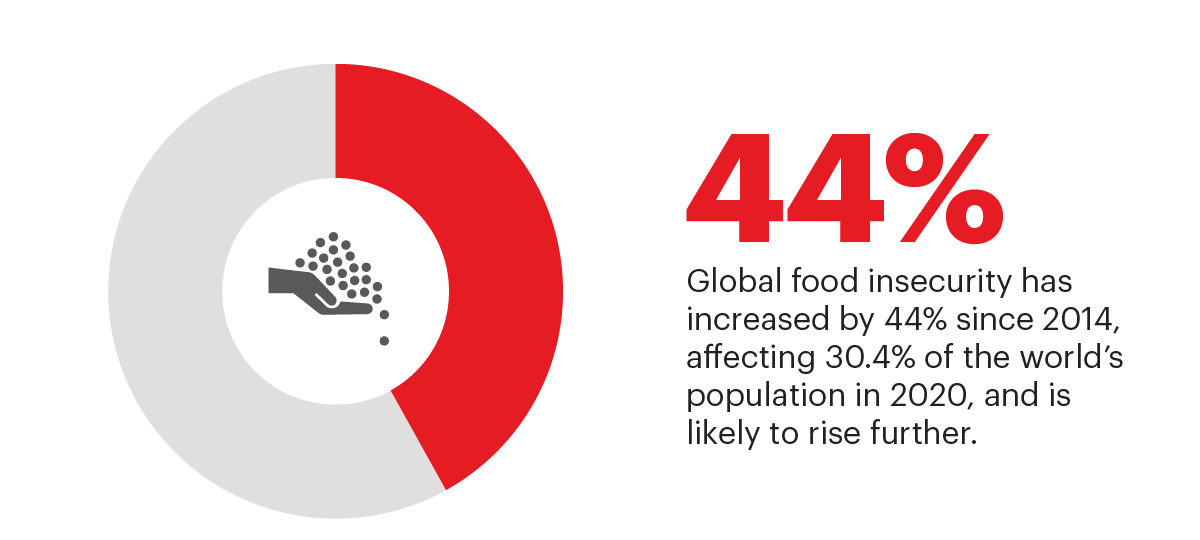

Based on current trends, future prospects are not encouraging. Both undernourishment and food insecurity have been steadily rising since 2015. This is the reversal of a long-established trend where undernourishment had been improving.

The factors causing this are complex, however, high population growth, lack of potable water and increasing land degradation are clear contributors.

Based on the current number of undernourished people and allowing for population growth, IEP projects the number of undernourished people to rise by 343 million people by 2050, to 1.1 billion. This is a 45 per cent increase.

The impact of ecological degradation on conflict is highlighted by the strong overlap between the countries with the highest levels of conflict, as measured by the Global Peace Index (GPI), and those with the worst ecological degradation.

Eleven of the fifteen countries facing the worst ecological threats are currently in conflict, and another four are at a high risk of substantial falls in peace. Examples include Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Niger, Burkina Faso and Pakistan.

Given the significant link between ecological fragility and conflict, addressing water availability, food security and high population growth in countries mired by conflict will improve prospects for lasting peace.

Highly resilient countries have the best ability to manage their natural resources while still catering for their socio-economic needs. Positive Peace is a proxy for socio-economic resilience and the attributes of Positive Peace allow for higher levels of adaptability.

This includes better water management, more efficient agricultural systems, and the capability to import food when local production is insufficient. No country with a high level of peace has an extremely poor ETR score, underscoring the relationship between ecological fragility and conflict.

On the other hand, eighty per cent of the countries with the worst ETR scores are also among the world’s least resilient. This indicates that these nations may not be able to mitigate the impacts of their rapidly changing environment.

The 30 countries facing the highest level of ecological threat are home to 1.26 billion people. These nations combine low socio-economic resilience with medium to extremely high catastrophic ecological threats.

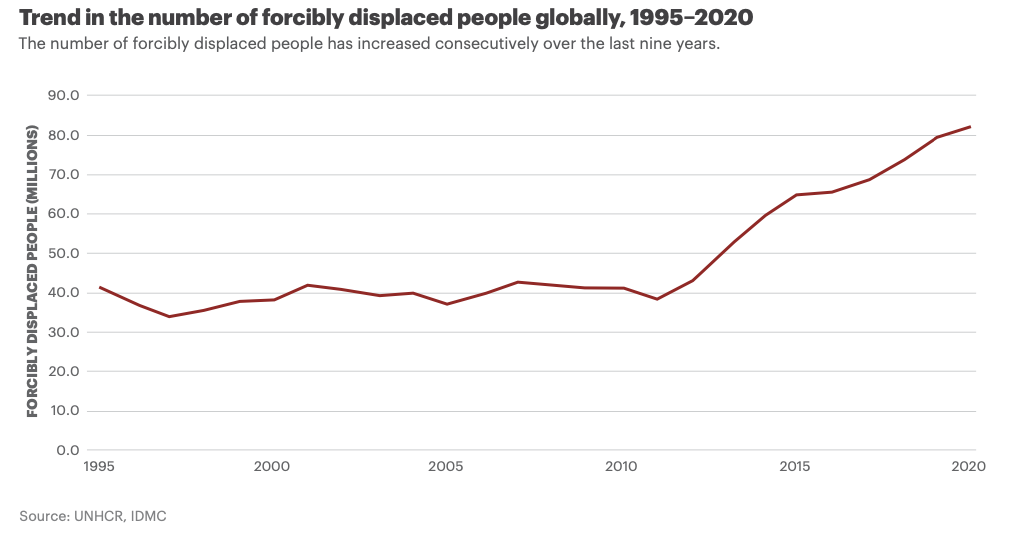

The number of people displaced by conflict has been steadily rising. At the end of 2020, 34 million people had been forcibly displaced from their home nations.

Of this total, 23.1 million people or 68 per cent came from these 30 hotspot countries. Without a reversal of ecological degradation, these numbers are likely to increase.

More positively, the 2021 Ecological Threat Report identifies that 46 countries face low ecological threat levels, with 35 exposed to very low threats. Eighty-nine per cent of these countries have high Positive Peace scores.

These countries also have low population growth. In 2021, their combined population is 1.96 billion people, and by 2050, this figure will slightly increase to 2.18 billion people. These countries are mainly located in Eastern and Western Europe, North America and South America.

Underlying the urgency of the situation, the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that in 2020, a total of 2.4 billion people, or 30.4% of the global population, are food insecure.

In 2020 the number of food-insecure people rose by 318 million people relative to the previous year.

The vast majority of this increase occurred in three regions: South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and South America, where the numbers of food-insecure people rose by 128 million, 86 million and 40 million, respectively.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of food insecurity, with 66 per cent of the population deemed food insecure. Sub-Saharan Africa also has the lowest societal resilience of all regions.

By 2050, sub-Saharan Africa’s population is projected to be 2.1 billion, a 90 per cent increase from today’s levels.

Such rapid population growth is unsustainable and could translate to hundreds of millions of additional food-insecure people over the next few decades.

Eleven countries in the region are expected to double their population between now and 2050.

The three countries with the largest projected increases in population are Niger, Angola and Somalia, where the populations will increase by 161, 128 and 113 per cent, respectively.

The Sahel is especially vulnerable. The region faces many converging and complex challenges such as civil unrest, weak institutions, corruption, high population growth and lack of adequate food and water.

These issues have formed a vicious cycle whereby ecological degradation and population growth have increased the likelihood of conflict and facilitated the rise of Islamist insurgencies.

There are gender differences in the way malnutrition affects human growth and development. The data indicates stunting and thinness markedly affects males more than females, especially in Africa, where stunting and thinness rates are twice as high for males than females.

The relationship between malnutrition and violence is not well researched, especially in areas suffering from prolonged conflicts.

In particular, the links between poor nutrition, brain development and emotional control needs to be studied more deeply, and whether hunger may act as a motivator for young males joining militias.

In 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, more than 10 per cent of young men suffer from very low body mass. These countries are also among the least peaceful in the GPI.

In 2020, nearly 170 countries closed their borders, either partially or completely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This severely affected refugee movement and resettlement.

In 2020, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of refugees resettled or naturalised was the lowest on record.

Only 250,000 refugees returned home compared to the pre-COVID average of 670,000 returnees. In Europe, Turkey hosted the largest number of refugees at 3.9 million, followed by Germany at 1.5 million and France at 550,000.

This report analyses and proposes a number of policy recommendations to improve the efficiency of interventions and break the vicious cycles that exist in many parts of the world.

1. International agencies need new integrated structures.

We recommend that integrations combine health, food, water, refugee relief, finance, agricultural, development and other functions.

This would create area-specific integrated agencies that would be agile and built for specific contexts while also providing a simplified chain of command, better allocation of resources and faster decision making.

This would align with the systemic nature of many of the problems. The focus should be on building societal resilience.

2. Many of the solutions to the ecological problems can generate income.

An example is the provision of water that can then be used to grow food. If businesses can garner a profitable return from ecologically positive investments, funds will naturally flow towards solutions.

These businesses need to be small scale and run by local business people. Better leveraging of carbon offsets for the local communities can also provide income.

3. Empowering local communities.

Community-led approaches to development and human security result in more effective programme design, easier implementation and more accurate evaluation.

Due to the strong bonds within communities, cooperatives can work well. This provides a mechanism for the pooling of resources and the dilution of costs.

In summary, ecological threats will continue to create humanitarian emergencies and will likely increase without a sustained effort to reverse the current trend.

Ecological threats are becoming more pronounced and affecting more people than ever. Building resilience to these threats will increasingly become more important and will require substantial investment now and into the future.

This is an excerpt from the Ecological Threat Report 2021, which analyses 178 independent states and territories and assesses threats relating to food risk, water risk, rapid population growth, temperature anomalies and natural disasters.

Read the report