As French influence has sharply declined, Russia is filling the void, raising questions about the future of counterterrorism efforts in the region.

This July, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger officially withdrew from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a 49-year-old union of 15 member states which encompassed almost 400 million people. The bloc served as a fundamental pillar of regional integration and security cooperation.

Since 2020, tensions within the bloc had been escalating, as all three nations were upended by military coups: Mali in 2020 and 2021, Burkina Faso in 2022, and Niger in 2023. Refusing to recognise each country’s military junta, ECOWAS imposed sanctions and temporary bloc suspensions to encourage a return to democratic practices, expecting the nations to ultimately rejoin the union. However, junta leaders strongly objected to the sanctions as “inhumane”; in the junta leaders’ words, the coups had been necessary to take “their destiny into their own hands.” The three nations outlined their grievances against ECOWAS in a joint communiqué published in January 2024, criticising the organisation for falling under the “influence of foreign powers” and favoring an adherence to democratic ideals over more pressing security matters. In place of the regional ECOWAS, junta leaders from the three states formed a trilateral defense pact, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), signed on July 6, 2024.

This geopolitical reconfiguration is the latest in a series of security realignments in the name of bolstering counterterrorism efforts in, and expelling external Western forces from, the Sahel region. The G5 Sahel, another anchor of regional cooperation, similarly fell apart after almost a decade of counterterrorism work. The coalition, comprising Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Mauritania, was established in 2014 to enhance regional security, and significantly transformed in 2017 to include French-backed military operations against jihadist groups.

In a comparable cycle to the ECOWAS disintegration, Mali’s junta leaders bristled at the G5 Sahel’s reaction to its 2021 coup, which included the G5 Sahel blocking Mali from assuming the group’s presidency and became the first to exit the coalition in May of 2022. Following their respective military takeovers, Burkina Faso and Niger followed suit, criticising the G5 Sahel’s failure to achieve its security goals. The two nations further denounced the intrusion of foreign interests which “denied the sovereignty” of the African states and treated their people “like children”. The remainder of the coalition was officially terminated on December 6, 2023, just three days after the withdrawal of Burkina Faso and Niger.

Security cooperation between France and its three former colonies, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, has become increasingly strained over the past decade. More than 60 years since the three nations gained their independence, French influence over its former African colonies continues to be a source of tension in their security cooperation.

The first major deployment of French troops to the Sahel took place in 2013 under Operation Serval, following an official request by the Malian government to combat a rebellion by ethnic Tuareg separatists. Despite a strained colonial history, French troops were reportedly “greeted as heroes” for providing military aid and found initial success in the defense of the capital, Bamako, and the recapture of northern Timbuktu and Gao from the insurgent group.

However, in 2014, the limited Operation Serval evolved into the more expansive Operation Barkhane, which ran from 2014 until 2022 and is widely viewed as a failure. With an annual budget of $US660 million and a deployment of 5,500 soldiers, concentrated in Mali but stationed across all G5 Sahel countries, Operation Barkhane delivered meager results while regional insurgencies continued to expand (both in number and intensity).

From the French side, Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian characterised Mali’s junta as “out of control” and an “illegitimate” partner in the fight against terrorism. Following reports of a potential Russian mercenary deployment to Mali, France similarly declared Russia’s presence “incompatible with French efforts. In response, Mali expelled French Ambassador Joel Meyer. Anti-French sentiment in Mali around Operation Barkhane’s ineffectiveness was further stoked by France’s reluctance to acknowledge battlefield errors and by perceived French insensitivity to civilian casualties. In fact, French General Didier Castres, former deputy chief of staff for Operation Barkhane, admitted that France took a patronising approach to security cooperation with Malian partners.

With political tensions at an all-time high, France announced its removal of troops from Mali in February 2022, with the remainder of Operation Barkhane formally ending that November.

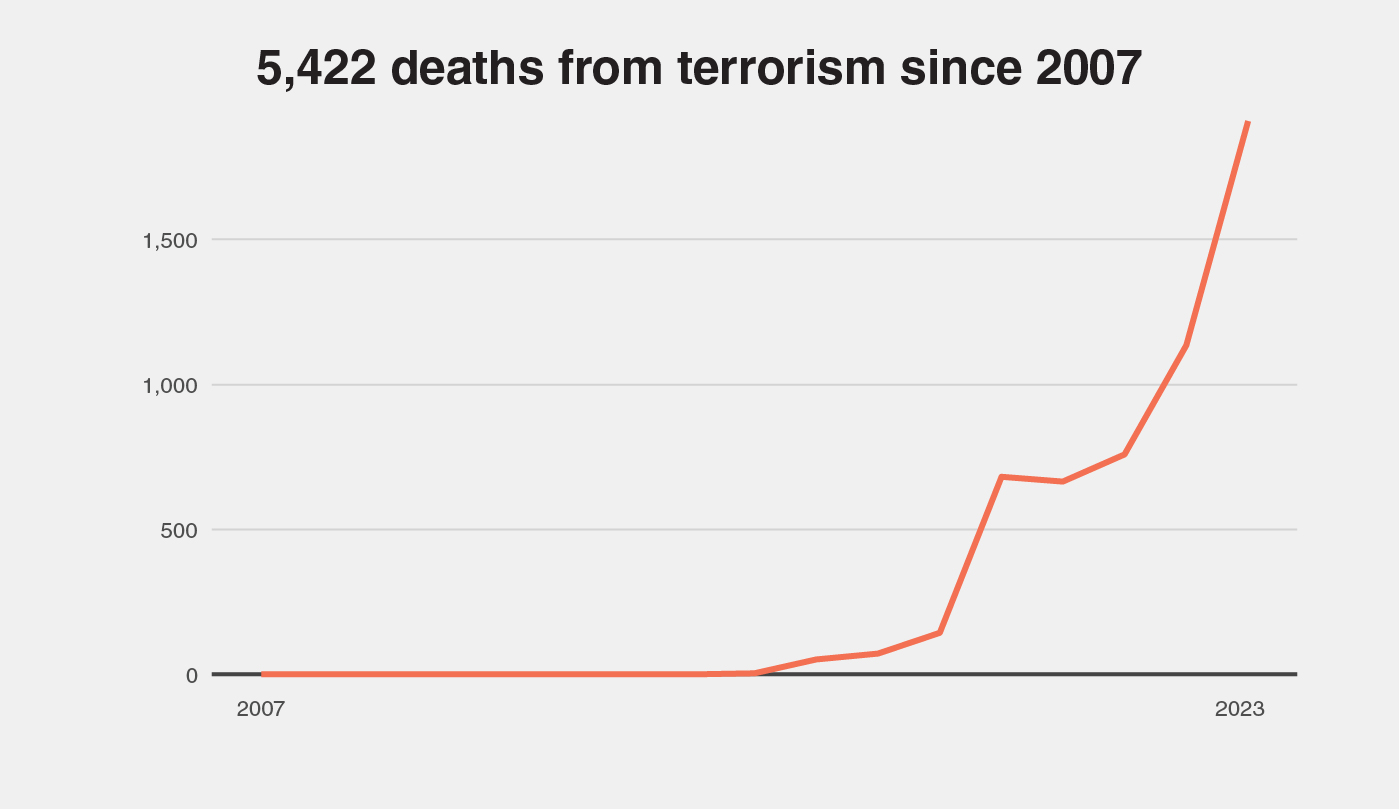

The failures of Operation Barkhane and Western-backed security efforts to counter terrorism are reinforced by the findings of the 2024 Global Terrorism Index (GTI). The GTI, which aggregates the total number of terrorist incidents, fatalities, injuries, and hostages into a single score, confirmed the Sahel region as the epicenter of global terrorism in 2024, with 4,000 deaths from terrorism – 47 percent of the global total. The past 15 years, which spans the bulk of French security cooperation and intervention in the Sahel, saw a 2,860 per cent increase in terrorism-related deaths and 1,266 per cent increase in incidents across the region.

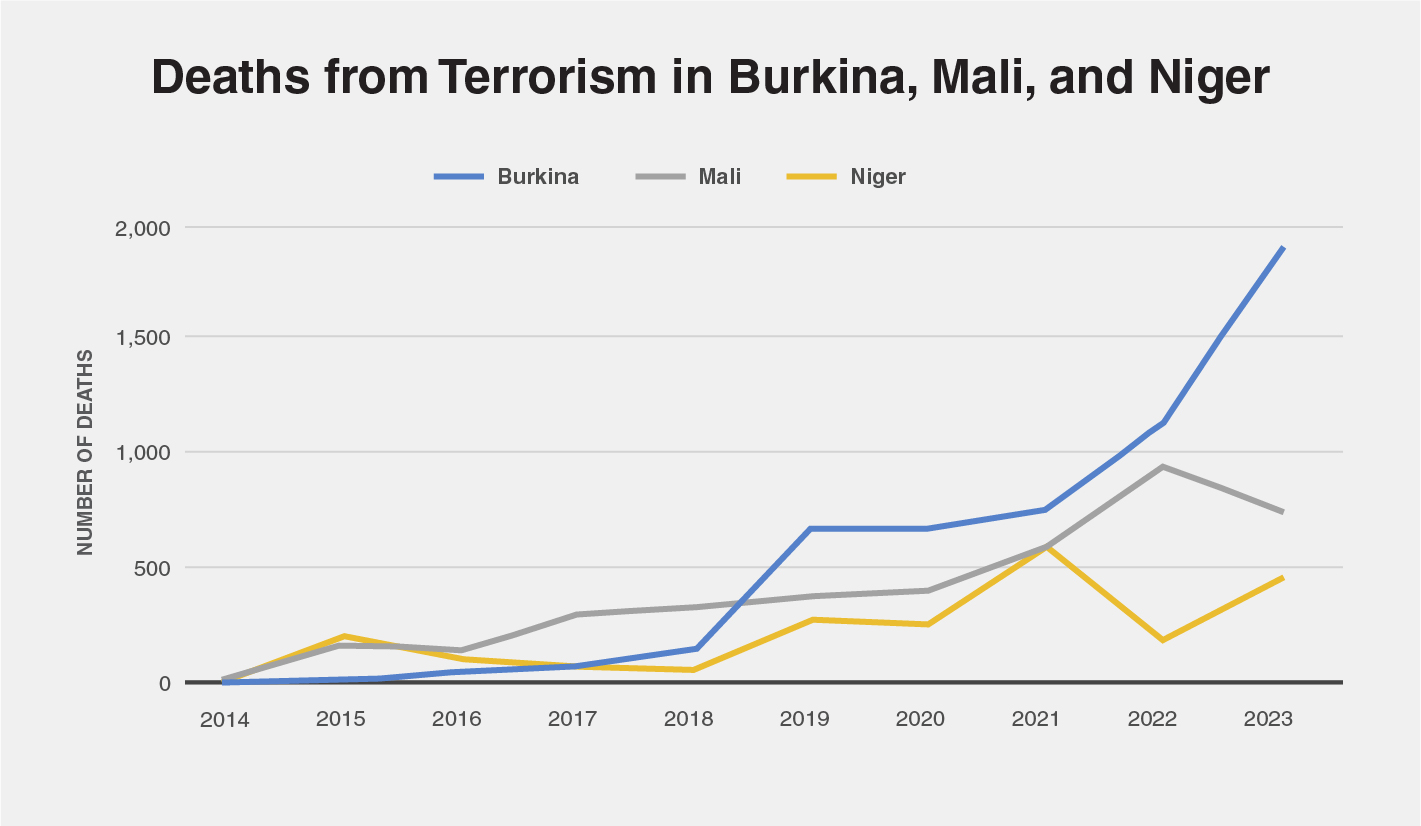

Of the 10 countries most impacted by terrorism, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger – all located in the former G5 Sahel – experienced the largest deteriorations in GTI rankings over the past decade. According to the report, in 2023, Burkina Faso suffered the highest global impact from terrorism, for the first time since the index’s inception in 2012. Deaths from terrorism increased in Burkina Faso by 68 per cent over the previous year, reaching 25 per cent of the global total. Terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso have also increased notably in lethality, with over seven deaths per attack in 2023, compared to an average of four the previous year. According to a Freedom House report, half of the country’s territory remains under the control of militant groups, beyond the state government’s authority.

This dramatic increase in terrorism in the Sahel is at odds with larger regional and global trends. In 2012 and 2013, the average GTI scores for the G5 Sahel countries were comparable to the global average, and only slightly higher than the average for Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 1). However, over the past decade, the impact of terrorism has shot up in the G5 Sahel nations, increasing by 206 per cent, compared to Sub-Saharan Africa’s increase of 36 per cent (and an overall global decrease of seven percent). Even in Libya, where Qaddafi’s death and the ensuing state collapse in 2011 triggered a proliferation of weapons and a flow of insurgents into the Sahel, the impact of terrorism has been steadily dropping since 2018.

Despite the billions of dollars spent, and in the face of significant civilian and soldier casualties, the decade of French-backed security efforts in the Sahel has proven ineffective in the fight against terrorism. Even with junta leaders’ repeated assurances of prioritising security, often seen as being at the expense of democratic practices and institutions, the security environment has continued to deteriorate since the French withdrawal. The key question now is whether adjusted strategies can do better.

Following the breakdown of the French-supported G5 Sahel, the exit from ECOWAS, and the formation of the trilateral defense pact AES, the former coup-leaders-turned-heads-of-state from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have deepened security ties with a new partner: Russia. The Wagner Group, a private Russian mercenary company, has reportedly been active in Africa since 2017, including deployments in Mali that began in 2021. Following Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin’s death in August 2023, the group rebranded as “Africa Corps,” signaling a serious escalation in Russian engagement in the Sahel.

In addition to providing weapons and development aid to the region, Africa Corps is now also deploying soldiers to Burkina Faso and Niger. The three heads of state, as well as other Sahelian security actors, have publicly referenced their strategic alliance with Russia (and most recently signed a satellite deal) emphasising Russian counterinsurgency strength and geopolitical neutrality – a stark contrast to the perceived primacy of French national interests in the region.

In late July 2024, Russian counterinsurgency effectiveness was in focus as approximately 50 Russian fighters, alongside their Malian counterparts, were killed in an al-Qaeda raid, Russia’s biggest loss of life in the Sahel to date. Mali accused Ukraine of aiding rebels in the raid and cut diplomatic ties. There were also reports of indiscriminate violence by Russian forces against Malian civilians.

How could a Russian-backed counterterrorism presence in the Sahel look different from French-supported efforts? While the Wagner Group’s technical detachment from the Russian government gave it operational latitude, the re-branded Africa Corps is affiliated with the Russian Ministry of Defense. Analysts are watching as to how Africa Corps will operate as a state-regulated agent and navigate the political constraints of the state actors.

Looking forward, there are a number of potential approaches for the actors in this process. France and ECOWAS could recalibrate their democratic expectations to maintain a long-term presence in the Sahel. As the impact of terrorism within the Sahel is at an all-time high, evolving security strategies could deliver an effective near-term response, but trade-offs may be required.