Cécile Guerin and Zoé Fourel look into the key narratives and implications of online Islamophobic hate speech in France.

This Dispatch draws on ISD’s ongoing work monitoring hateful speech in the French online ecosystem. It follows-up on previous research conducted by our Digital Analysis Unit including the Mapping Hate Online report, and a recent briefing which examined hateful speech online in France during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since 2015, successive waves of terrorist attacks in France have triggered a surge of Islamophobia across the country and an increase in hate crimes targeting the Muslim community, especially in the direct aftermath of terrorist attacks. 54 anti-Muslim incidents were registered in the week following the Charlie Hebdo attack. The French Muslim community is gripped by a climate of acute insecurity. A Fondation Jean Jaurès study conducted in 2019 revealed that 42% of French Muslims felt they experienced discrimination based on their faith, with the number rising to 60% for Muslim women wearing a headscarf.

Following the latest spate of attacks in October 2020, concerns have emerged relating to the government’s proposal for a “bill on Republican principles” (former “bill against separatism”), aimed at cracking down on Islamist extremism. This bill is seen by many as potentially stigmatising for Muslim communities. Recently adopted amendments to the bill could for instance introduce restrictions on Muslim religious practice, including banning the headscarf for girls under 18 in public spaces, or preventing mothers who wear a headscarf from taking part in school trips. These developments have raised concerns about the risk of institutional Islamophobia and the broader impact on French society.

Over the last few months, ISD has conducted an analysis of anti-Muslim discussion in France on Twitter and Facebook. This analysis complements the more detailed research carried out in ISD’s study La pandémie : terreau fertile pour la haine en ligne, released in February 2021. Using a list of hateful keywords associated with anti-Muslim discourse, researchers identified publicly available French-language posts on Twitter and Facebook using social media listening tools Brandwatch and CrowdTangle between 1 September 2020 and 1 February 2021 (Facebook) or 1 March 2021 (Twitter). This time frame corresponds to the second wave of COVID-19 in France and the series of terrorist attacks that struck the country in the autumn of 2020, including the beheading of teacher Samuel Paty in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine on 16 October and the Nice stabbing on 29 October.

Increase in anti-Muslim discussion after the October terror attacks

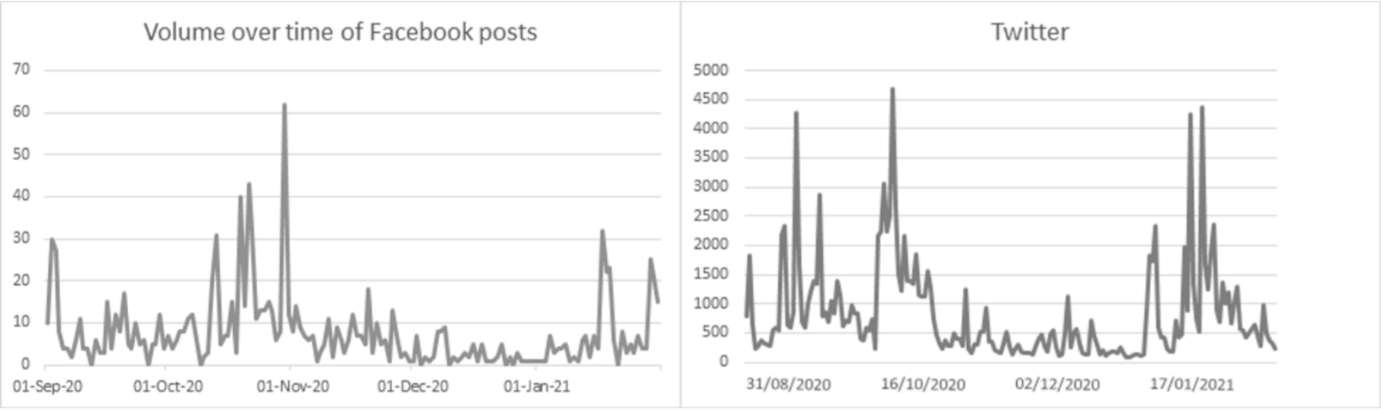

Both on Twitter and Facebook, anti-Muslim discussion soared in late October following the two terror attacks.

On Twitter, the main peak in volume of content occurred on 21 October, with an 823% increase in posts from 20 to 23 October. The top 10 posts on these days all reacted to the terrorist attack in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, presenting the attack as a sign of France’s alleged ‘islamisation’ and outwards signs of Islamic faith (using as the headscarf) as a danger to French society. 8 of the 10 tweets with the highest reach used the term “voile islamique” (Islamic veil) and described the headscarf as a reflection of France’s alleged islamisation and women’s oppression. Several far-right personalities such as Robert Ménard and Rassemblement National (RN) official Julien Odoul called for banning the headscarf in public spaces.

The second highest peak in conversation took place on 4 February 2021, and was linked to discussions in the National Assembly of the “proposition de loi confortant les principes républicains” (Strengthening Republican principles bill). Twitter users widely condemned the comments of sLa France Insoumise (LFI) MP Eric Coquerel, who compared the headscarf to a wedding veil in order to diminish the attacks on headscarf wearing. The top 10 posts on the day were produced by right-wing (e.g. Eric Cioti) or far-right (e.g. Jean Messiah, former RN and RN MEP Mathilde Androuët) public figures, presenting the headscarf as a symbol of female oppression.

The third and final peak took place on 31 January 2021 and was linked to an event staged by self-identified ‘feminist collective’ Nemisis, a femonationalist organisation which openly promotes an anti-immigration and Islamophobic agenda and has staged anti-Muslim actions (e.g. ‘no hijab day’ in Paris). 7 out of the 10 posts with the highest reach supported Nemesis’s action, condemning their arrest by the police.

Peaks in discussion on Facebook mirrored trends on Twitter. Researchers saw a sharp increase in posts following the 16 October 2020 killing of Samuel Paty, followed by a second spike in discussion on 19-20 January 2021 after the French government presented the “bill on republican principles” to Parliament. While the terror attack prompted posts about the alleged ‘islamisation’ of the country, the late January spike led to renewed discussion about the headscarf.

Key narratives

ISD researchers analysed posts with the highest reach on Twitter and Facebook, and identified three key topics of discussion:

➜ The condemnation of the alleged ‘islamisation’ of French society: Several far-right figures were central to the promotion of this narrative on Twitter including former RN official Jean Messiah (9 out of 30 posts with the highest reach were from Messiah’s Twitter account) and ultra-conservative commentator Eric Zemmour. One of Messiah’s tweets denounced ‘Arab-African-Muslim immigration’ and promoted the idea that white French people would soon be a minority in France, an echo to the great replacement conspiracy theory. Zemmour praised the pan-European far-right Identitarian movement.

➜ Anti-headscarf discourse: Both on Twitter and Facebook, the most shared posts denounced some Muslim women’s choice to wear a headscarf or hijab. Of the top 30 tweets analysed, 14 mentioned the term “voile” (veil) and 12 used the islamophobic term “voile islamique” (Islamic veil). These posts came as a reaction to the Republican principles bill, which plans to ban the headscarf for underage girls. Several right-wing and far-right public figures openly criticised women wearing a headscarf, including RN leader Marine Le Pen and RN senator Stéphane Ravier, as well as Les Républicains (LR) Eric Cioti and Laurent Wauquiez. Of the top 30 posts on Facebook, nine mentioned the headscarf.

➜ Reactions to the terror attack in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine: Of the 30 posts receiving the highest level of interactions on Facebook, five mentioned the attack in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine and one mentioned the attack in Nice a few days later. Posts about the attacks frequently presented outward signs of Muslim faith (e.g. the headscarf, mosques and halal food) as a threat to the country. Some posts implicitly likened Muslims to terrorists (see below).

➜ Posts presenting Muslims as a threat: Other posts focused on a range of topics, including death threats against 17-year-old teenager Mila following her criticism of Islam; an alleged attempted attack in Paris by a man disguised as a Muslim woman (shared by the far-right outlet Epoch Times); and alleged threats by Muslim men against ex-Muslim women who choose not to wear the headscarf.

Influencers

On Twitter, the top 10 most active accounts ISD analysed all belonged to individuals (no public figures), although two accounts demonstrated bot-like behaviour. All the accounts focused on discussing the notion of France’s “islamisation”. Four of them openly supported Marine Le Pen, two self-identified as “patriots” (in their Twitter biography) and two appeared to be based in Greece.

Most active public pages and groups on Facebook were dominated by official and unofficial accounts of elected members of right-wing populist parties and far-right media outlets, including the official Facebook page of RN party and its leader Marine Le Pen as well as RN elected official Robert Ménard’s page. They also included the official Facebook pages of far-right news and media outlets including Valeurs Actuelles and TV Libertés, as well as the pages of fringe far-right websites such as Breizh Info and Damoclès. This suggests that elected officials from right-wing populist parties with large audiences on social media played a key role in driving these conversations about the Muslim community.

Implications

ISD’s analysis suggests that peaks in anti-Muslim discourse in France can be tied to specific events, with terror attacks in particular providing a rallying point for anti-Muslim online mobilisation. Anti-headscarf rhetoric and allegations that France is undergoing a process of “islamisation” are prominent both on Twitter and Facebook, the latter echoing the “great replacement” conspiracy theory.

Far-right outlets and accounts as well as more traditional right-wing public figures are active in promoting these narratives, highlighting the mainstreaming of islamophobic discourse in French public life. The prominence of anti-headscarf rhetoric and attacks on Muslim women highlights the need for an intersectional analysis of anti-Muslim discourse, as women are targeted by hateful speech both on accounts of their gender and faith.

This article originally appeared on the Institute for Strategic Dialogue’s Digital Dispatches blog, and has been republished with permission.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Vision of Humanity.