As we explore in the Mexico Peace Index 2024, this deterioration is caused particularly by the violent contests between organised criminal groups over territory and control of illicit rackets. Between 2015 and 2022 the number of organised crime-related homicides grew from around 8,000 to around 20,000, while the number of non-organised crime-related homicides has remained relatively stable at around 10,000 to 12,500 per year.

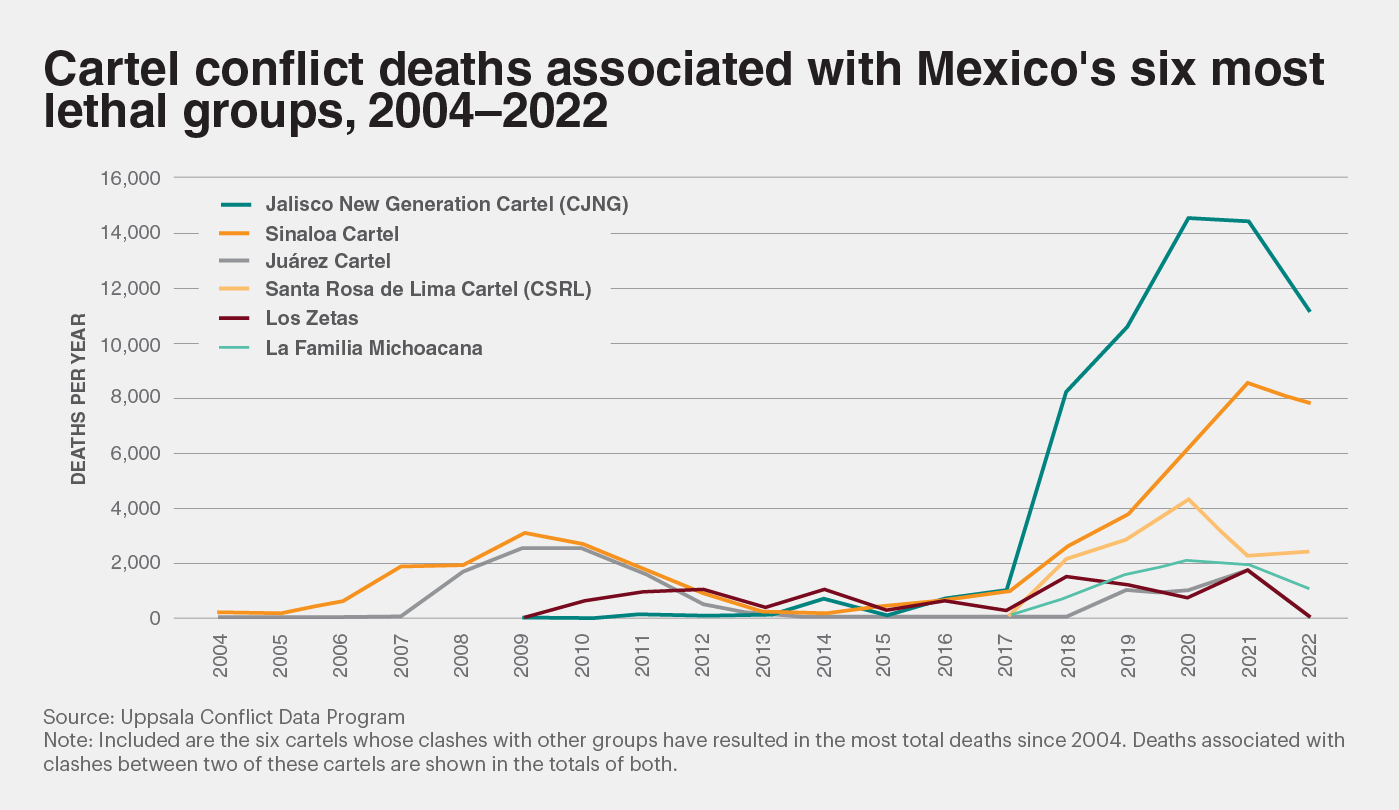

According to data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), only 160 incidents of cartel clashes resulting in at least one death were recorded in 2013. In 2021, the number of such clashes peaked at 3,753 and fell to 2,248 in 2022.

The sustained high levels of conflict between organised crime groups follow the fragmentation of Mexican cartels after the launch of the war on drugs in 2006 and the implementation of the kingpin strategy, which sought to combat criminal organisations by targeting their leadership. While drug trafficking operations were formerly controlled by a handful of dominant organisations, in several instances the kingpin strategy contributed to such organisations breaking up into smaller but more violent groups. According to UCDP records, the number of criminal organisations involved in at least one death, increased from just four in 2007 to 25 in 2022.

Throughout the 2010s, this trend was seen, for example, in the emergence of Los Caballeros Templarios as an offshoot of La Familia Michoacana, the independence of Los Zetas from the Gulf Cartel, the separation of the CJNG from the Sinaloa Cartel, and the subsequent split of the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel (CSRL) from the CJNG. The Sinaloa Cartel has also seen violent fissures following the arrest of its former leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, specifically between a faction affiliated with Guzmán’s former partner, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, and a faction affiliated with Guzmán’s sons, known as Los Chapitos.

The heavily militarised Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), considered by the US Department of Justice to be one of the world’s five most dangerous transnational criminal organisations, rose to prominence in the past decade, and particularly since 2017, through a violent national expansion campaign and by catering to the high demand for fentanyl and methamphetamine in the US market. The CJNG now holds a dominant presence in six states and a significant presence in an additional 20. Its stronghold is on the western coast, in Jalisco and neighbouring states, but its operations span across all the country’s regions. The CJNG’s expansion increased inter-cartel conflict across Mexico.

The figure below shows the number of cartel conflict deaths per year associated with Mexico’s six most lethal criminal groups since 2004. While each group was linked to at least 7,000 deaths, the murders associated with the country’s two most powerful cartels, the Sinaloa and CJNG – including their clashes with each other and with other cartels – are several times more numerous than those associated with the other groups.

The vast majority of both the overall killings and those specifically associated with these two groups have occurred since 2017, the year that an alliance between them reportedly broke down. In the period between 2013 and 2017, clashes involving at least one of these two groups accounted for just 38 per cent of all cartel conflict deaths, but from 2018 to 2022 they accounted for 64 per cent of such deaths.

Despite this, the UCDP data suggests that in more recent years, the deaths from cartel conflict have been on the decline. Between 2021 and 2022, its records show the number of such killings dropping by about one fourth. A similar trend is observable in data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which shows fatalities associated with cartel violence dropping by about one fifth between 2021 and 2022. The ACLED data, however, also shows cartel-related fatalities remaining virtually unchanged between 2022 and 2023.

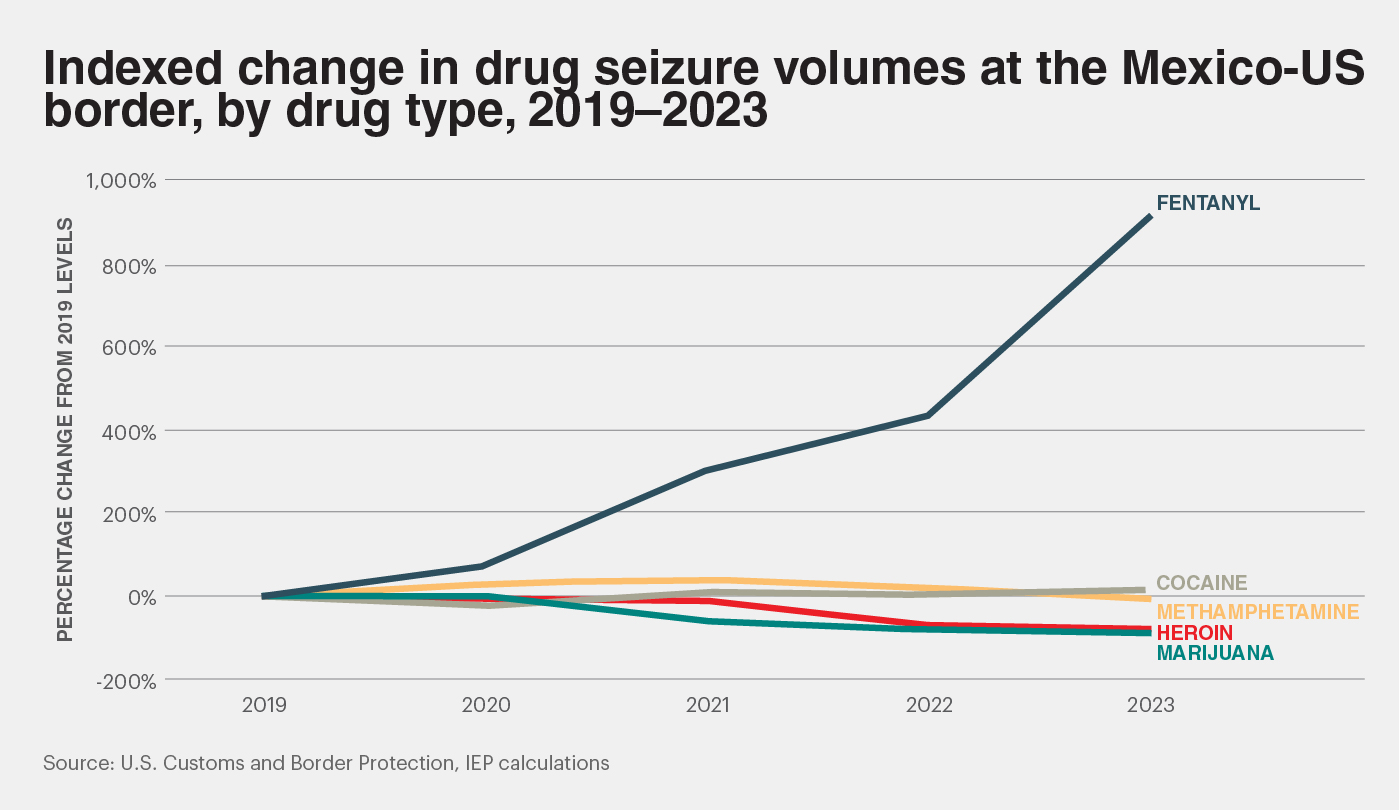

Mexico’s drug trafficking organisations have made significant changes to the drugs they produce over the past decade to adapt to significant shifts in the US market. In particular, these changes include a decline in demand for plant-based drugs such as marijuana and heroin and a massive increase in demand for synthetic drugs, particularly opioids.

The decline in demand for marijuana in Mexico can be attributed to the legalisation and decriminalisation of marijuana in most US states. In 2013, when only a few U.S. states. had legalised recreational marijuana use, marijuana seizures along the U.S.-Mexico border were just under 1,350 metric tons. By 2023, with the majority of the US population able to legally access the drug, the volume of seizures declined to around 60 metric tons, a 96 per cent drop.

With marijuana’s massive decline in profitability, drug trafficking organisations have had to expand their trafficking of other drugs, with fentanyl being the most prevalent. As shown in the figure below, the amount of fentanyl seized by US Customs officials at the Mexico-US border has skyrocketed; the amount seized increased tenfold between 2019 and 2023.

The shift to fentanyl production has been highly lucrative, as fentanyl is extremely potent, relatively cheap to produce and often sold in pill form, meaning that criminal groups can make much larger profits, relative to the volume of the drug being trafficked. The markup on fentanyl prices when it is sold and distributed can be up to 2,700 times the price it takes to produce it. Because of its low price, fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs such as heroin or cocaine to make them more potent and cheaper to produce. The drug’s potency has led to an increase in overdose deaths in both the United States and Mexico in recent years. Fentanyl and similar opioids are reportedly linked to more deaths in Americans under the age of 50 than any other cause.

In addition to the increased fentanyl being seized at the US border, the amount seized within Mexico has also been growing. In just the first half of 2023, 1,727 kilograms of fentanyl were seized by Mexican authorities, almost as much as what had been seized over the course of a whole year in 2022, which was previously the highest year on record for domestic seizures.

Despite the large amounts of fentanyl that were seized, methamphetamines experienced by far the most dramatic rise within Mexico. In the first half of 2023 alone, more than 138,000 kilograms of methamphetamine were seized by Mexican authorities, three times as much as in the entire year of 2021, which previously held the record.

The rise in domestic consumption of amphetamine-type substances is a result of the market shift to synthetic drugs. Mexican organised crime groups became the primary producers and suppliers of methamphetamine to the United States after 2005, when legislation was passed in that country that limited the importation of key precursor ingredients for methamphetamine production. The upsurge in synthetic drug consumption, both in Mexico and the United States, has been driven by their extreme addictiveness; the ease with which they can be produced, transported, and sold; and their high levels of profitability for organised crime groups.

Data from the Mexican Observatory for Mental Health and Drug Consumption reveals that abuse of methamphetamine by Mexican citizens is a rising problem in the country. Over the past few years, the drugs that people have sought treatment for have shifted from predominantly alcohol and marijuana toward amphetamine-type substances, which include methamphetamine and ecstasy. Between 2014 and 2022, the rate of people seeking treatment for amphetamine-type substances increased by 400 per cent, compared to a 34 per cent decline in the rate for alcohol.

Overall, the landscape of organised crime in Mexico has undergone profound transformations over the past decade. As cartels adapt to shifts in enforcement strategies and drug demand, their conflicts have become deadlier, altering the dynamics of violence across the country. The recent surge in synthetic drug trafficking, particularly of fentanyl and methamphetamines, reflects a critical pivot in the operations of these criminal enterprises. While there is a noted decrease in violence and shifts in drug trafficking patterns, the underlying issues of organised crime remain deeply entrenched.

For comprehensive insights into the state of peacefulness in Mexico, download and read the full report: