In this year’s edition of the Mexico Peace Index (MPI), we have included of a new indicator: fear of violence. Based on national survey data, the indicator refers to the degree to which citizens perceive the state in which they reside to be unsafe.

Replacing the detention without a sentence indicator used in previous editions of the index, the fear of violence indicator provides for a broader assessment of peace. Going beyond the prevalence of external manifestations of violence, it captures prevailing public sentiment towards safety and security. This shift highlights a more dynamic approach to understanding and quantifying peace, ensuring that the index remains a relevant tool for assessing national stability and peace.

Over the past nine years, the percentage of people in Mexico who feel unsafe in their states of residence has experienced a net deterioration of 1.3 percentage points. In 2015, 73.2 per cent of the population reported feeling unsafe, while 74.6 per cent reported feeling unsafe in 2023. During this period, 11 states showed improvements in fear of violence, whereas 21 states deteriorated. Notably, Coahuila made significant strides; the proportion of its population feeling unsafe fell dramatically from 74.9 to 44.1 percent, marking a more than 30 percentage point drop. Conversely, Colima experienced the largest deterioration in that time, with the percentage of its population feeling unsafe rising from 56.5 per cent in 2015 to 80.9 per cent in 2023.

Fear of violence had its lowest rate on record in 2012, with 66.6 per cent of the country feeling unsafe. However, this sense of security was short-lived as the rate rose by 5.8 percentage points over the next four years. Beginning in 2016, the situation began to worsen significantly, with fear of violence peaking at 79.4 per cent in 2018. Since that peak, there has been a gradual but steady improvement, with the rate declining to 74.6 per cent by 2023.

The shifts in public sentiment towards safety have closely mirrored the country’s overall peace score. Like the fear of violence indicator, the overall peace score in Mexico rapidly deteriorated beginning in 2016, falling by 17.2 per cent over the following three years. However, it has shown signs of gradual improvement since then. This correlation underscores IEP’s definition of peace, which considers both the absence of violence and the absence of fear about violence.

The relationship between overall levels of peacefulness and perceptions of safety is multifaceted, influenced by a variety of factors. According to the global survey data collected in the 2023 Safety Perceptions Index, crime and violence were the second most commonly cited risks since at least 2019, suggesting that violence, more than other risks, profoundly affects public perception of safety. An average of 35.8 per cent of respondents across 121 countries reported being “very worried” about violence crime, whereas only 5.6 per cent had reported experiencing it firsthand in the last two years. This significant gap – more than six times the number of people fearing violence than experiencing it – in perception is especially pronounced in Mexico, emphasising the importance of this indicator’s addition to the MPI.

The report indicated that “crime and violence” were identified as the top safety concerns by 46.3 per cent of the population, ranking Mexico among the top five countries globally where citizens perceive crime and violence as their primary concern. This widespread apprehension is mirrored in the 2023 state-by-state fear of violence scores. For instance, Baja California Sur exhibited the lowest fear rate, with only 33.4 per cent of residents feeling unsafe, whereas Zacatecas had the highest, with 91.9 per cent of residents feeling unsafe—a consistent increase from the previous year.

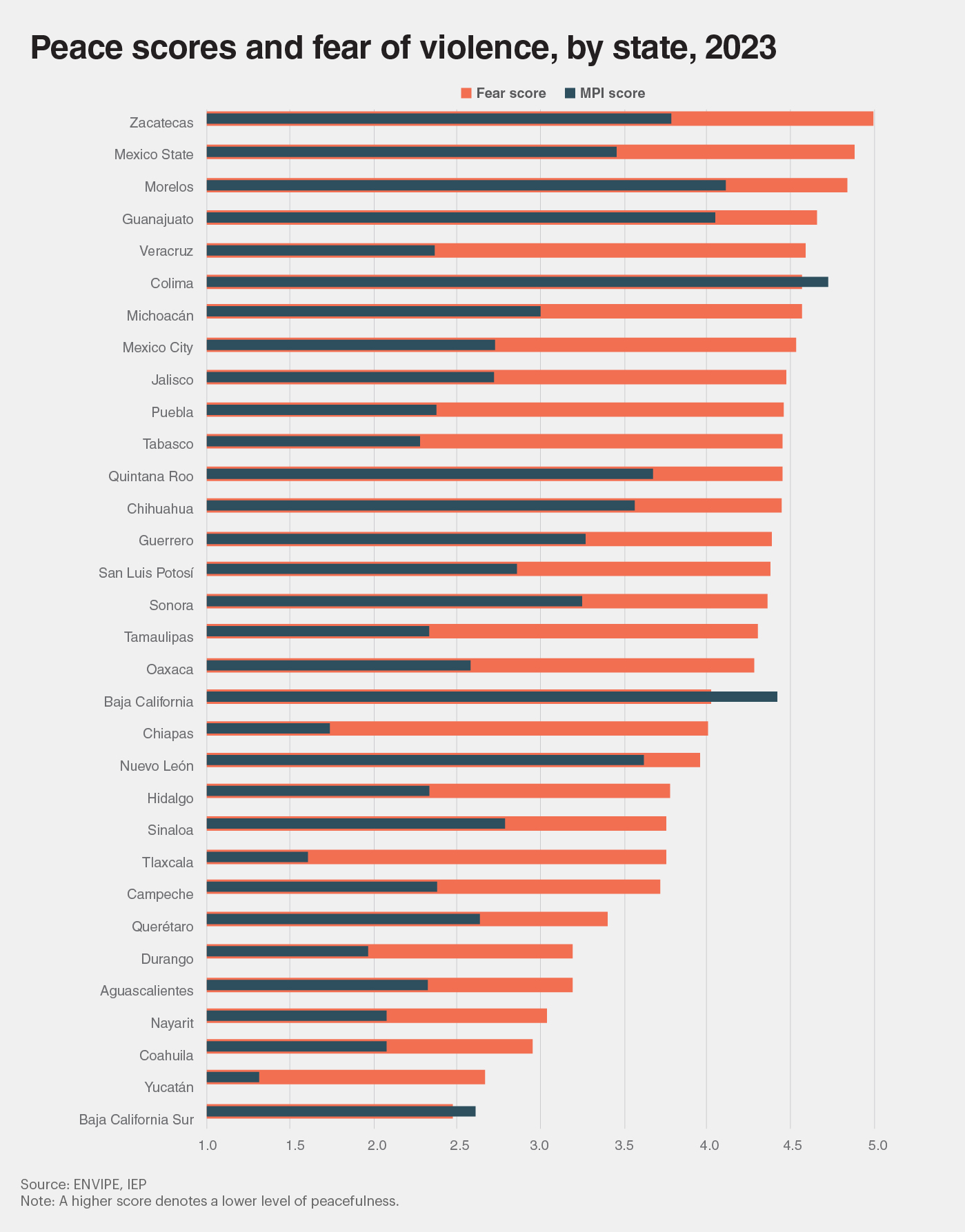

As is shown by the following figure, while fear of violence score tracks very well with overall peace score, most states’ perceived safety levels are worse than the actual conditions suggest. With a fear of violence score of 4.007 and an overall MPI score of 1.738, Chiapas recorded the largest discrepancy between its fear of violence score and its overall peace score. This disparity points to the influence of disproportionate media representation and personal experiences with crime, particularly with organised crime, which has become increasingly visible in certain states. The second and third largest discrepancies were recorded in Veracruz and Tabasco, respectively. Only three states – Colima, Baja California, and Baja California Sur – registered MPI scores worse than their fear of violence scores.

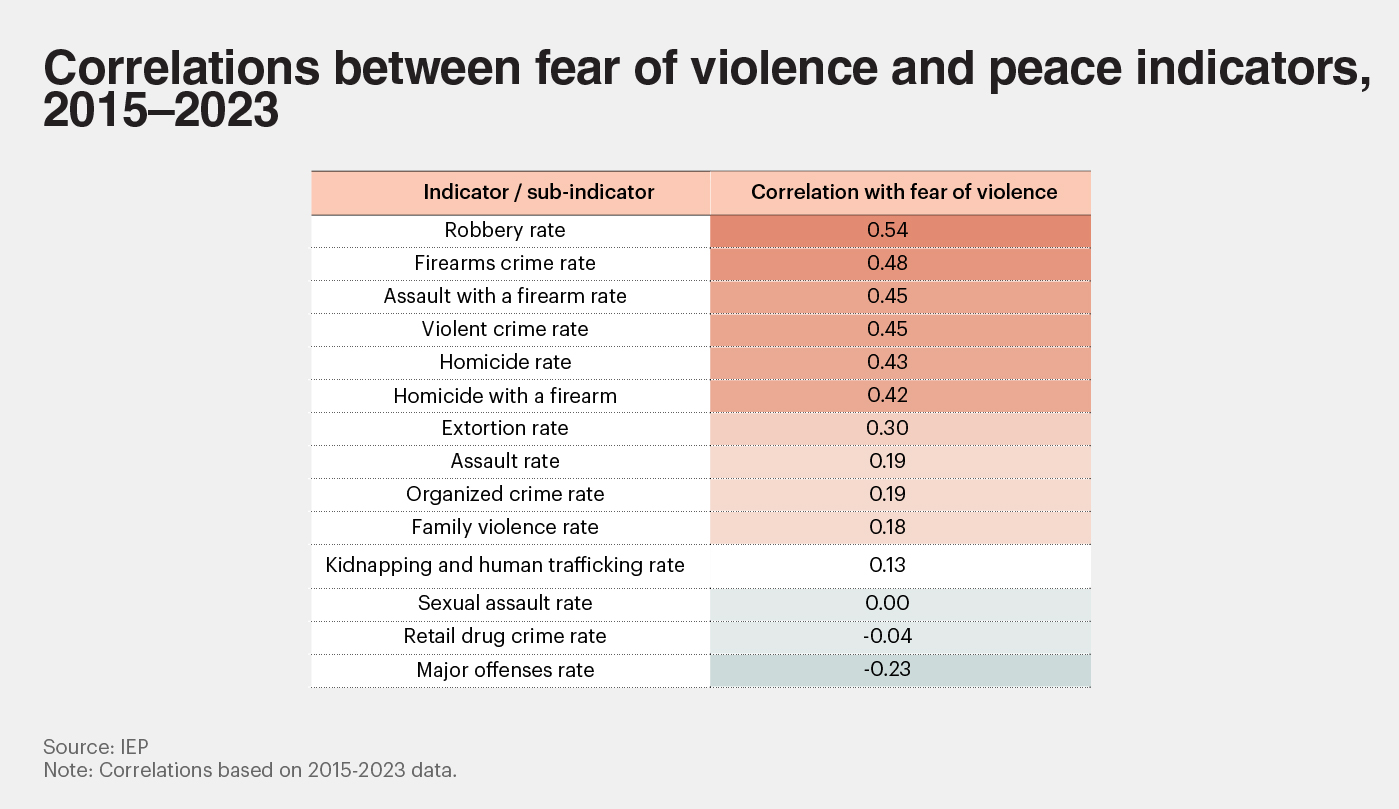

The correlation between various crime rates and the fear of violence shown in the following figure, further illuminates this dynamic. Analysis of crime and fear across states from 2015 to 2023 shows varied correlations, with robbery rates exhibiting the strongest link to fear levels. Given that robbery is a common crime that directly affects many citizens’ lives, this correlation is not surprising. Robberies make up two-fifths of all crimes experienced in Mexico. It reveals how direct and indirect experiences of specific crimes can shape broader perceptions of safety and contribute to an overall climate of fear.

This complex web of factors—ranging from media portrayal and personal experiences to the visible effects of organised crime—shapes public perceptions of violence and safety in Mexico. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers aiming to address the root causes of fear and improve both the reality and the perception of safety across the nation.

The impact of firearm-related crimes on public safety perceptions is also significant, particularly when compared with other crime types. After robbery, crimes involving firearms, along with the overall homicide rate, demonstrate the highest levels of correlation with fear of violence rates. This suggests that the real or perceived threat of lethal violence, especially in relation to the prevalence of gun violence, exerts a strong influence on citizens’ sense of safety. The widespread presence of firearms in Mexico significantly limits access to a full range of human rights, contributing heavily to the proliferation of fear. Research underscores that gun violence not only directly impacts health and life but also exacerbates discrimination and disrupts education and employment within communities, thereby magnifying its effects on societal stability.

In contrast to the impactful nature of firearm-related crimes, other types of crimes show varied levels of correlation with public fear. Notably, except for extortion, organised crime sub-indicators such as major offenses and retail drug crimes exhibit only a weak or even negative correlation with rates of fear. This is likely due to these crimes not directly impacting the everyday life of the average Mexican citizen, thus not eliciting significant levels of concern. Extortion, being the most prevalent among organised crime types, shows a moderate correlation (r = 0.30) with fear rates, reflecting its direct impact on public perception.

Further examining the correlations, violent crime sub-indicators, apart from robbery, tend to show low correlation levels (r < 0.20) with fear of violence rates. Crimes such as assault, family violence, and sexual assault, though severe, typically affect specific segments of the population and may not directly impact the broader community, which might explain the subdued correlation with public fear.

These distinctions in how different crimes influence public perceptions are crucial for a holistic evaluation of peace through perceptions of safety. Recognising that the perception of safety can influence community stability as much as the actual rates of violence is vital. By shedding light on these patterns and correlations, the fear of violence indicator proves instrumental in providing a more accurate portrayal of peace and security in Mexico.

For comprehensive insights into the state of peacefulness in Mexico, download and read the full report: