“While Chile successfully built resilience to earthquakes following a history of devastating impacts, Haiti lacks the coping capacity for disaster recovery.”

Looking at the example of earthquakes in Chile and Haiti shows how the impacts of natural disasters differ significantly between countries with different levels of Positive Peace.

The Ecological Threat Register (ETR) from the Institute for Economics and Peace measures ecological threats that countries are facing, with projections through 2050.

What’s more, the ETR combines measures of resilience with ecological data to highlight countries least likely to cope with ecological shocks.

Chile and Haiti are among the most earthquake-prone countries in the world and are situated along the Pacific “Ring of Fire”, where earthquakes and volcanic eruptions frequently occur.

While Chile has successfully built resilience to earthquakes following a history of devastating impacts, Haiti lacks the coping capacity for disaster recovery.

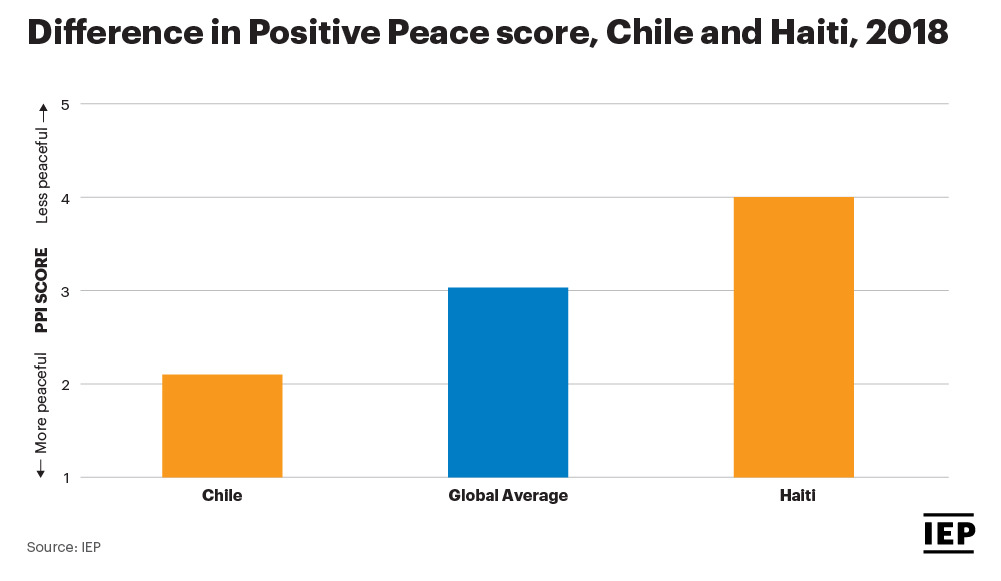

This infographic shows the difference in Positive Peace score between both countries.

In 2010, the magnitude-7.0 earthquake that struck Haiti was a catastrophic event exacerbated by the extreme vulnerability of the population and the lack of preparedness and response capacity of national authorities.

The earthquake was one of the biggest natural disasters in the country’s history resulting in over 200,000 fatalities and the displacement of approximately 1.5 million people.

Prior to the earthquake, Haiti suffered from high levels of poverty and weak institutions of governance. As a result, the country’s vulnerability increased in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. The slow distribution of resources in the days after the earthquake resulted in civil unrest and looting.

Additionally, government capacity was severely disrupted. The disaster killed or injured approximately 20% of federal employees, destroyed a quarter of government buildings and damaged almost all major infrastructure in Haiti.

Damage and losses were estimated to be equivalent to 120 per cent of Haiti’s GDP.

In 2001, Haiti’s National Disaster Risk Management System (SNGRD) was signed into effect.

This proved effective in the 2008 Hurricane season, with substantially fewer deaths recorded than previous hurricane seasons. However, the 2010 earthquake was beyond the capacity of the SNGRD due to its unexpected catastrophic nature.

The lack of political stability has had a significant impact on the continuity and effectiveness of Haiti’s response to disasters. Haiti also lacks any comprehensive data collection on natural disasters. In addition, it has no enforced building codes or nationwide early warning system.

In contrast, Chile’s extensive disaster response preparations and early detection systems substantially limited the impact of the magnitude-8.3 earthquake. In April 2015, the earthquake resulted in 12 fatalities with approximately 60 houses destroyed and a further 200 damaged.

Early detection and efficient communication networks were critical in Chile’s response. In 2015, Chilean officials were able to detect the earthquake and track tsunami waves before they occurred.

After the tsunami warning and declaration of a disaster area, almost one million people evacuated Choapa and Coquimbo.

Chile has improved its disaster response after its history of strong earthquakes. For example, in 2010 an 8.8-magnitude earthquake occurred off the coast of central Chile.

Together the earthquake and subsequent tsunami caused destruction across southern and central Chile. The disaster resulted in over 500 fatalities and destroyed over 200,000 homes.

In response, the country updated building codes. Now, all new buildings in Chile must be able to withstand a 9.0-magnitude earthquake.