Western great powers are finding themselves increasingly limited in their capacity and inclination to intervene in foreign conflicts. This trend has been shaped by numerous unsuccessful interventions and peacebuilding attempts. The US and European powers are also focused on the conflicts in the Ukraine and Gaza which is consuming them both politically and militarily.

Additionally, the looming threats of major conflict in East Asia pull away what little attention remains for managing global peace and security.

The world has seen a resurgence of great power competitions reminiscent of the Cold War. Three key geopolitical trends help explain why the nature of conflict is changing in the 21st century.

Although the US remains a preeminent force in global politics, its dominance over conflict management has noticeably declined over the past two decades. This shift can be attributed to its prolonged military engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, which have sapped resources and focus, alongside related power struggles in Syria and the broader Middle East.

US foreign policy has continuously shifted over the past three decades, from the interventionist approaches under President Bill Clinton, to the War on Terror under George W. Bush dominated by Middle Eastern interventions. President Obama’s tenure saw a mix of interventions and pragmatic realpolitik which reduced unilateral actions, while President Trump embraced an “America First” policy, scaling back many diplomatic endeavours. The Biden administration has maintained a form of interventionism but focused on providing military assistance over direct involvement and only in specific conflicts like those in Ukraine and Gaza.

US power is declining relative to other great powers such as China and Russia, which are expanding their global influence, aiming to match US influence and power. China is seeking to establish itself as the foremost global superpower through strategic investments and partnerships worldwide, especially in the Pacific. The European Union is struggling to agree on a coherent foreign policy. This is epitomised by the conflicting views of Germany and France on how to deal with Russia in relation to its invasion of Ukraine.

Emerging powers such as India are shaping security dynamics in South Asia and the Indo-Pacific, often in competition with China. India will likely become more influential in the future. India’s economy grew by 7.7 per cent in 2023 and 6.5 per cent in 2022. India’s population is roughly the size of China’s and will substantially pass it over the next decade, while Western countries are moving manufacturing from China to India due to perceived political risk. India is also well educated, containing a substantial middle class whose per capita income is rising. The rising relative economic might of India can be leveraged into geopolitical influence.

Further, a host of middle powers, including Türkiye, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Israel, Indonesia, Iran, Egypt, South Africa, and Nigeria, are more actively engaging in global affairs. The Global South is increasingly reluctant to align strictly with great powers, choosing instead to assert their own interests. This growing multipolarity means that small and middle-power states often engage with multiple great and regional powers.

In regions like the Sahel, the influence of traditional powers is waning. France has withdrawn from Mali and Niger, while its influence in Burkina Faso is also diminishing. The US is also leaving its military bases in Niger and Chad. In their wake, Russian and Turkish private military and security companies have deployed, with Türkiye using Syrian fighters to secure its interests. This diffusion of power indicates that no single nation is likely to dominate global policy on conflict management as the US once did, marking an unpredictable significant shift in international relations.

The conflict in Sudan, which erupted in April 2023, highlights the internationalisation of contemporary warfare, where both diffusion and distraction have hindered international resolution efforts. Stemming from decades of civil war, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have divided the country, fighting for control, and supported by other ethno-political militias and factions.

Sudan is now facing the world’s worst refugee crisis with over 10 million people displaced and credible reports of atrocities by both SAF and RSF. UN estimates of up to 15,000 killed in two RSF massacres in El Geneina in Darfur suggest catastrophically large death tolls, with some estimating up to 150,000 killed.

The focus of the US and EU on other regions like Ukraine and Gaza has limited their capacity to influence the Sudanese conflict.

External actors are having a significant impact by supporting competing sides, with the SAF backed by China, Russia, Iran, and regionally by Egypt, while the RSF has nearly matched military capabilities by capturing SAF bases and receiving support from the UAE, Chad, Russian PMSC Africa Corps, (formerly known as the Wagner Group) and the Libyan general Khalifa Haftar. The RSF’s access to weapons and logistics, including man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) that challenge SAF’s air superiority, further complicates the conflict. The focus of the US and EU on other regions like Ukraine and Gaza has limited their capacity to influence the Sudanese conflict.

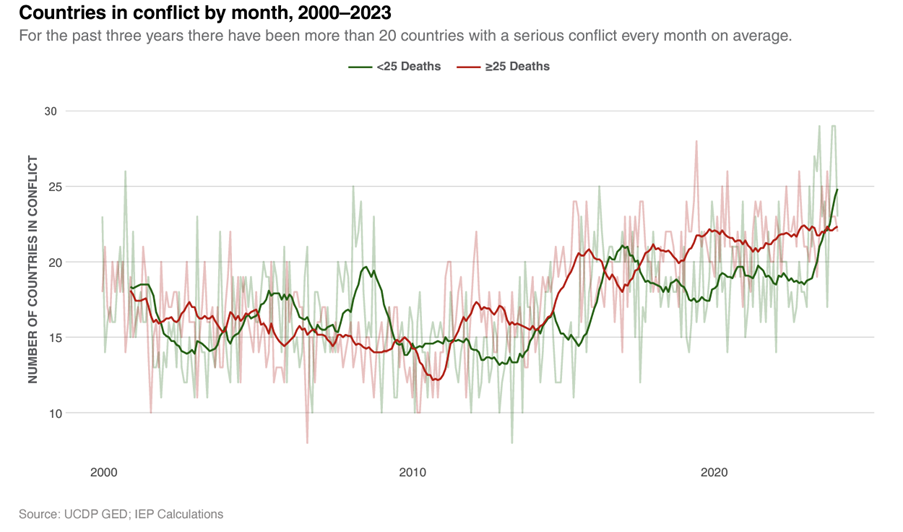

The increasing number of active conflicts may be limiting the ability of great powers to effectively intervene in conflict. It shows the one year moving average for conflicts with more and less than 25 deaths per month for the period 2000 to 2023. There are now an average of 25 active major conflicts a month, and a further 20 or so minor conflicts, compared to a decade ago when the average was less than 15 major active conflicts a month, and 17 minor conflicts.

Since the October 7th attacks in Israel, Western focus has pivoted sharply towards the war in Gaza, marking a significant shift from the sustained attention on Ukraine throughout 2022 and 2023. The attention paid to these two conflicts is understandable, as one is the largest war in Europe since World War II and the other a longstanding Middle Eastern conflict with potential for regional escalation. However, the focus on these two conflicts has meant many other conflicts go relatively unnoticed, including in Myanmar, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nagorno-Karabakh.

The conflict in Myanmar has evolved dramatically, from mass protests against the February 2021 coup to an armed resistance encompassing a coalition of groups. These include long- established ethnic armed groups and a network of people’s defence forces. In late 2023, a large-scale offensive dubbed Operation 1027 by three ethnic armed groups captured significant territories from government forces, including areas bordering India and China. China interceded, negotiating an agreement, keeping the border open and resulting in a lessening of hostilities in the area. The government is struggling to control parts of the country which are effectively under the control of various ethnic factions or the armed wing of the National Unity Government opposition.

The eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been mired in conflict for decades, involving national armed forces, rebel groups, local militias, and foreign troops. However, recent events have received relatively little attention, despite the displacement of at least 5.6 million people across multiple conflicts and the associated humanitarian crisis.

In 2023, the M23 rebel group increased its control in North Kivu and, as of May 2024, is close to the regional capital, Goma. M23 controls many mining activities including one of the world’s largest coltan mines which is a crucial resource for modern electronics, receiving substantial support from Rwanda, including troops and arms. The conflict in the DRC receives scant international attention. After 14 years MONUSCO, the world’s largest and most expensive peacekeeping mission, will be leaving the DRC. The mandate was cancelled by the DRC government due to perceived ineffectiveness. It will be replaced by troops from the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

This conflict, which had been ongoing since at least 1991, culminated swiftly in September 2023. Azerbaijan launched a successful military offensive that resulted in about 200 deaths before the unilateral surrender declaration by the leaders of Artsakh, the Armenian name for Karabakh. The roughly 100,000 Karabakh Armenians residing in the territory promptly fled to Armenia.

The conflict received minimal attention as Russia, traditionally active in managing this dispute, showed a disinclination to enforce peace agreements despite having peacekeepers on the ground. Russia’s focus has shifted toward fostering closer ties with Azerbaijan, which has helped it evade sanctions after the invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile, European powers, seeking oil and gas alternatives to Russian supplies from Azerbaijan, and a preoccupied US have been unable to provide effective intervention.

Elsewhere, ongoing conflicts in Ethiopia, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Haiti persist with minimal prospects for resolution and potential for significant escalation. These lower-profile conflicts suffer from a global lack of appetite for intervention or significant measures to end them. Additionally, diplomatic attention is limited, with efforts being diverted elsewhere. These limitations mean that conflicts may last longer, with increased costs in lives and economic damage. Furthermore, humanitarian aid is particularly strained as governments, grappling with inflationary pressures, are reluctant to commit additional funds to foreign aid despite the growing needs.

These shifts in the geopolitical landscape, the increased number of unresolved conflicts, combined with the limited bandwidth of the international community means that some well-known conflicts are likely to receive the bulk of aid and attention, while less publicised crises receive much less attention and aid than is required. The potential implications of these limitations are profound, as the global conflict management capacity continues to be tested by the immediate urgencies of crises in Europe and the Middle East.